Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The use of an autogenous soft tissue graft that did not include the epithelium layer was first reported in 1974 by Alan Edel. Edel secured the tissue onto a connective tissue recipient bed, similar to a free gingival graft technique, and left it exposed to the oral environment to increase the width of keratinized tissue. Langer and Calagna first introduced the term “subepithelial connective tissue graft” (SCTG). They harvested autogenous connective tissue from the palate and placed it underneath a partial-thickness flap to esthetically rehabilitate soft tissue irregularities and concavities of resorbed edentulous ridges. During the 1980s, many authors attempted to develop soft tissue grafting techniques that could improve anterior esthetics in edentulous areas, providing a natural emergence profile for pontics of fixed partial dentures.

A rationale soon evolved that an esthetically pleasant smile results when pink and white esthetics are in harmony; that is, the soft tissue profile is just as important as the proportions, shape, and color of the teeth and toothlike restorations in the formulation of an attractive smile. Subsequently, renowned clinicians such as Shapiro, Miller, and Langer used SCTG to develop periodontal plastic surgery techniques to treat gingival recessions and ridge deformities. The use of the SCTG has since become the standard of care to treat gingival recessions and provide root coverage in clinical practice.

Not until the mid-1990s was the SCTG used in conjunction with dental implant cases to improve esthetics. Since then, numerous publications have verified the predictability of autogenous soft tissue grafts around implants, including their excellent clinical results and long-term stability. The aim of this chapter is to enhance the implant surgeon’s armamentarium with techniques that go beyond the placement of a functional restoration in an edentulous site to the restoration of soft tissue harmony so that the implant-supported restoration is indiscernible from a natural tooth. Clinicians who practice implant dentistry should consider aiming higher than just osseointegration of the implant to achieve an esthetically successful outcome. The esthetic success of an implant case lies in attention to fine details, through which adequate connective tissue can (1) provide a natural emergence profile for the restoration through healthy peri-implant gingiva, (2) create a labial profile over the bone and implant body similar to the root prominence of a natural tooth, and (3) support papillae, fill interdental embrasures, and hide the restorative components of the implant restoration ( Figure 27-1 ).

History of the Procedure

The use of an autogenous soft tissue graft that did not include the epithelium layer was first reported in 1974 by Alan Edel. Edel secured the tissue onto a connective tissue recipient bed, similar to a free gingival graft technique, and left it exposed to the oral environment to increase the width of keratinized tissue. Langer and Calagna first introduced the term “subepithelial connective tissue graft” (SCTG). They harvested autogenous connective tissue from the palate and placed it underneath a partial-thickness flap to esthetically rehabilitate soft tissue irregularities and concavities of resorbed edentulous ridges. During the 1980s, many authors attempted to develop soft tissue grafting techniques that could improve anterior esthetics in edentulous areas, providing a natural emergence profile for pontics of fixed partial dentures.

A rationale soon evolved that an esthetically pleasant smile results when pink and white esthetics are in harmony; that is, the soft tissue profile is just as important as the proportions, shape, and color of the teeth and toothlike restorations in the formulation of an attractive smile. Subsequently, renowned clinicians such as Shapiro, Miller, and Langer used SCTG to develop periodontal plastic surgery techniques to treat gingival recessions and ridge deformities. The use of the SCTG has since become the standard of care to treat gingival recessions and provide root coverage in clinical practice.

Not until the mid-1990s was the SCTG used in conjunction with dental implant cases to improve esthetics. Since then, numerous publications have verified the predictability of autogenous soft tissue grafts around implants, including their excellent clinical results and long-term stability. The aim of this chapter is to enhance the implant surgeon’s armamentarium with techniques that go beyond the placement of a functional restoration in an edentulous site to the restoration of soft tissue harmony so that the implant-supported restoration is indiscernible from a natural tooth. Clinicians who practice implant dentistry should consider aiming higher than just osseointegration of the implant to achieve an esthetically successful outcome. The esthetic success of an implant case lies in attention to fine details, through which adequate connective tissue can (1) provide a natural emergence profile for the restoration through healthy peri-implant gingiva, (2) create a labial profile over the bone and implant body similar to the root prominence of a natural tooth, and (3) support papillae, fill interdental embrasures, and hide the restorative components of the implant restoration ( Figure 27-1 ).

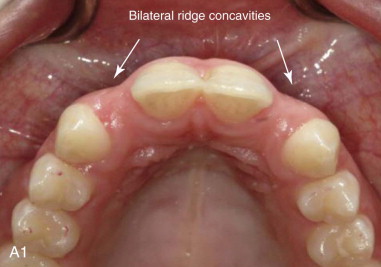

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Practically every implant placement, especially in the esthetic region, constitutes an indication for soft tissue grafting. The inevitable alteration of the alveolar ridge dimensions that follows every tooth extraction results in the placement of the implant in a site that has undergone a reduction in tissue volume in comparison to neighboring dentate sites. This discrepancy is more pronounced in single-implant sites where a concavity is formed between the edentulous site and the root prominence of the neighboring dentate sites ( Figure 27-2 ). SCTGs can be used in those cases to reconstruct the gingival dimensions of the site, create the illusion of root prominence, and increase the width of the crestal peri-implant gingiva, providing sufficient tissue for a restoration that closely resembles a natural tooth.

The long-term stability of pink esthetics around a dental implant prosthesis has been strongly correlated with an adequate soft tissue thickness around the implant, a thick peri-implant biotype. When a thin biotype is diagnosed, a subepithelial connective tissue graft can be used to prevent potential long-term recession of the facial mucosa margin.

Factors that should be considered when evaluating the need for soft tissue grafting include :

- 1.

The level of clinical attachment on adjacent teeth to support papillary height

- 2.

The thickness of the coronal soft tissue margin to ensure a proper emergence profile

- 3.

The thickness of labial soft tissue to simulate root eminence and prevent transillumination of underlying metallic structure

- 4.

The position of the mucogingival junction and amount of keratinized tissue, which should allow harmonious blending with that of the adjacent teeth

Connective Tissue Grafting During Implant Surgery

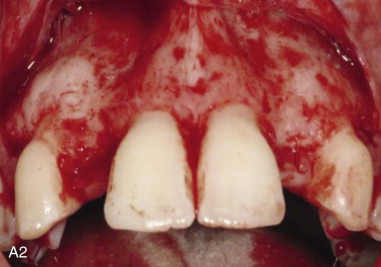

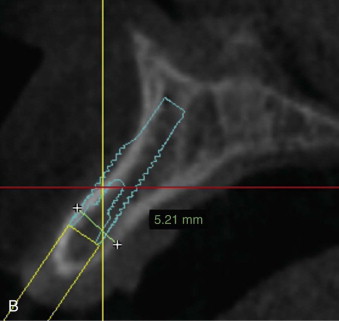

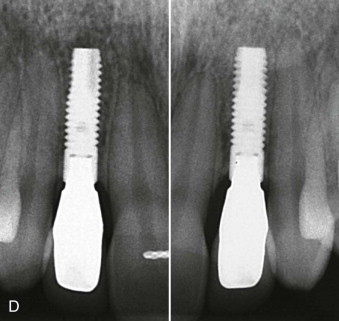

A thorough, three-dimensional (3D) preoperative evaluation of the edentulous site is critical to properly plan an implant case that will result in a pleasing esthetic outcome. Two diagnostic variables that should be taken into account preoperatively are bone and soft tissue volume. The long-term stability of esthetics around an implant requires that the implant be surrounded by about 1.5 to 2 mm of vital bone. A site that shows adequate bone thickness for ideal 3D placement of an implant should also be evaluated for its soft tissue profile and the need for soft tissue grafting. Soft tissue augmentation can be performed simultaneously with implant placement and/or during the second-stage surgery (as described later in the Technique section). There is no evidence in the literature to support any advantage of simultaneous soft tissue augmentation over augmentation during second-stage surgery. Both treatment modalities have been shown to lead to better esthetics and increased soft tissue thickness. Even though both techniques yield favorable esthetics, in accordance with the authors’ experience, the earlier the intervention is performed, the more options the clinician has to better control the final outcome. For instance, when the residual ridge has undergone significant atrophy, simultaneous soft tissue augmentation in conjunction with first-stage surgery allows enough healing time to properly assess the area at the time of second-stage surgery. Additional soft tissue augmentation then can be performed simultaneously with uncovering of the implant or implants to achieve a more ideal outcome.

Managing Esthetic Failures

Connective tissue grafting also can be used as a “rescue procedure” to manage esthetic complications associated with implants. Labial inclination of implants and/or buccal placement contributes to a thin tissue biotype; this may result in the grey shade of the implant structure showing through the tissue, recession, and exposure of the titanium implant neck, for an inharmonious emergence profile of the implant-supported restoration. These complications produce an ersatz appearance of the smile. Soft tissue grafting after implant placement is a relatively minimally invasive technique that can be used to correct complications associated with soft tissue color mismatch to a level below clinical perception.

Limitations and Contraindications

General and specific limitations apply to the use of this soft tissue augmentation technique around dental implants. Underlying medical conditions that present as contraindications to surgical intervention are general contraindications. Medical conditions associated with collagen disorders, such as erosive lichen planus, or pemphigoid may pose a risk to the viability of autogenous connective tissue grafts placed on a recipient bed that exhibits a pathologic healing mechanism. There is no published evidence to support the use of this technique in such cases.

A key determinant in the success of this technique is revascularization of the graft. Heavy smoking can have a deleterious effect on the survival of grafted soft tissue by producing gingival vasoconstriction that often results in necrosis of the soft tissue graft. Nicotine-associated vasoconstriction, in combination with lack of adherence of the fibroblasts and an alteration in immune response, diminishes the chance for a successful outcome. Preoperative assessment should attempt to identify such patients, and the clinician must inform the patient of the potential adverse effects associated with smoking. Ideally, the surgeon should have the patient first participate in a smoking cessation program and then return later for surgery. However, in clinical reality, this is not always an option. The surgeon must make the final decision on whether to proceed with a delicate procedure in a smoker, bearing in mind that proper patient selection is imperative to achieving the desired treatment outcome. Preoperative interruption of the smoking habit, followed by a smoke-free period during the critical stages of initial revascularization, and adjunctive measures (e.g., use of nicotine patches) should be the minimum precautions taken before subjecting a smoker to soft tissue grafting. Local factors that may also limit patient selection include lack of adequate tissue thickness at the palatal donor site and restricted surgical access to intraoral donor sites, such as the posterior aspect of the hard palate or tuberosity.

Technique: Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft (SCTG)

Step 1:

Treatment Planning

As with all surgical procedures, treatment planning is the cornerstone of success. Preoperative identification of potential soft and/or hard tissue deficiencies allows for construction of an implant restoration that closely mimics the natural dentogingival complex and blends in with the rest of the dentition in a pleasing esthetic fashion. The surgeon should decide preoperatively whether soft tissue augmentation alone will be adequate to develop the desired treatment outcome or whether bone augmentation also is needed to achieve ideal implant positioning and soft tissue esthetics.

Step 2:

Bone Grafting

In some cases hard tissue augmentation is required in addition to soft tissue grafting. The existing morphology of the underlying hard tissue should be evaluated radiographically. The 3D positioning of the implant should allow the fixture to be surrounded by at least 1.5 mm of bone circumferentially. When planning treatment for an esthetic case, the clinician should bear in mind that both adequate bone and soft tissue are required for an esthetically pleasing outcome. The treatment alternatives for bone augmentation of ridge defects are discussed in a later chapter (see Chapter 20 , Site Preservation and Ridge Augmentation) ( Figure 27-3, A ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses