Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Simple extractions are a mainstay of oral and maxillofacial surgery. The first mention of tooth extraction was found in the writings of Hippocrates, and the procedure was described by the Roman Celsus in the first century AD. Tooth extractions were performed by tooth-drawers and lower barber-surgeons. In the eighteenth century, the first description of extraction instruments was published. In modern times, advanced dental techniques allow the maintenance of teeth. Preventive dentistry has given dental patients the knowledge and tools to better care for their teeth and retain them longer. Still, many patients require routine extractions and preservation of bone for dental implants. Basic exodontia includes the use of instruments to perform simple luxation techniques, bone expansion, and forceps delivery of the tooth. This chapter presents the basic instruments used for simple extractions, the surgical techniques for extracting teeth in different areas of the mouth, and the preservation of bone for future restoration.

History of the Procedure

Simple extractions are a mainstay of oral and maxillofacial surgery. The first mention of tooth extraction was found in the writings of Hippocrates, and the procedure was described by the Roman Celsus in the first century AD. Tooth extractions were performed by tooth-drawers and lower barber-surgeons. In the eighteenth century, the first description of extraction instruments was published. In modern times, advanced dental techniques allow the maintenance of teeth. Preventive dentistry has given dental patients the knowledge and tools to better care for their teeth and retain them longer. Still, many patients require routine extractions and preservation of bone for dental implants. Basic exodontia includes the use of instruments to perform simple luxation techniques, bone expansion, and forceps delivery of the tooth. This chapter presents the basic instruments used for simple extractions, the surgical techniques for extracting teeth in different areas of the mouth, and the preservation of bone for future restoration.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

It is important to consider the patient’s overall health during the interview at the initial consult appointment. In addition to understanding the mechanics of tooth removal, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon must be aware of the patient’s psychological, physiologic, and pathologic status. No aspect of simple tooth extraction is more important than the careful preoperative examination of the patient. This includes an updated medical history, any indicated laboratory tests, physical exam, oral exam, and dental radiographs. Box 10-1 presents conditions that warrant extraction. It is important first to attempt to save the tooth through restorative, endodontic, and periodontic treatment. Only if the initial therapy fails should the tooth be extracted.

- •

Carious and nonrestorable teeth

- •

Failed endodontic treatment

- •

Poor periodontal prognosis

- •

Impacted teeth and periapical pathology

- •

Necrotic teeth

- •

Supernumerary teeth

- •

Crowding/nonfunctional teeth

- •

Orthodontic considerations

- •

Deciduous teeth interfering with eruption of permanent teeth

- •

Root fracture

- •

Dental pain and unwillingness to undergo necessary treatment

- •

Interference with prosthodontic needs

Limitations and Contraindications

After a complete history and review of systems, the surgeon may ask the patient about certain medical conditions that may make the patient unsuitable for a routine dental extraction under local anesthesia. Some examples are bleeding dyscrasias, liver disease, immunocompromised conditions, cardiac disease, and coronary artery disease. A thorough history of radiation and bisphosphonate therapy should be determined and appropriate measures taken.

During the clinical and radiographic assessments, certain key findings should alert the surgeon that a routine dental extraction may need to be converted to a surgical approach. Such findings include teeth with gross amounts of decay through the furcation or below the level of the alveolus, bony pathology, tooth impaction, root dilacerations, and a previous history of endodontic therapy. Certain anatomic barriers may require additional skill and expertise, such as for extraction of a maxillary molar in the presence of a pneumatized maxillary sinus or extraction of a mandibular molar with roots that approximate the inferior alveolar nerve canal.

Technique: Instrumentation for Routine Extractions

Dental Extraction Forceps

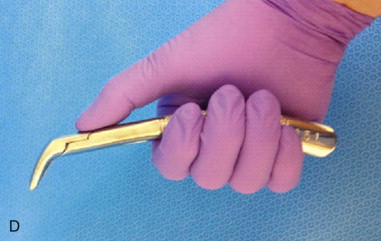

A wide variety of forceps has been developed for specific surgical applications, but the basic principle has remained constant. The majority of dental extractions can be performed using a limited number of instruments. Dental extraction forceps are principally used to grasp a tooth and apply a force that gives the surgeon leverage impossible to achieve without the use of such an instrument. Forceps are designed with two blades and handles joined by a hinge. The blades of extraction forceps are designed to grasp the buccal and lingual surfaces of the tooth. The concave shape of the blades allows the surgeon to apply the maximum surface area of the blades on the tooth, distributing the forces evenly and thus giving a greater degree of control. When holding the forceps, the further the distance from the hinge, the more force between the beaks. This results in better control of the tooth, and the forceps is less likely to slip. The beaks of the forceps are aimed in an apical direction toward the long axis of the tooth. All extraction forceps can be seen as modifications of this basic design. An assortment of forceps with blades and handles has been designed for specific teeth in the dental arch, to enable the surgeon to achieve the most appropriate adaptation and to facilitate control of the forces applied to the tooth.

Maxillary Forceps

Extraction forceps for the six anterior maxillary teeth include maxillary universal forceps (#150) and maxillary straight forceps (#99C). The beaks of the forceps are applied labially and palatally and directed in an apical direction parallel to the roots of the anterior maxillary teeth. The maxillary straight forceps offers an advantage for maxillary anterior teeth, allowing easy forces applied apically, palatally, labially, and especially rotationally. The further posterior the extraction, the more difficult it is to use the straight forceps due to obstruction of the lower lip and mandibular teeth; in addition, the contour of the posterior maxillary teeth makes it difficult to adapt the beaks to the tooth surface. The maxillary universal forceps can be used in a similar fashion, but it has a curved beak and handle, which keeps them above the lip while still directing the beaks in an apical direction parallel to the roots of the teeth, avoiding iatrogenic injury. Additionally, these forceps can be used to extract maxillary posterior teeth ( Figure 10-1, A and B ).

Extraction forceps for the maxillary posterior teeth include the maxillary universal forceps mentioned previously and forceps with beaks specifically designed to fit more complex root forms, such as #89 and #90 forceps. These forceps have a concave palatal beak that can adapt to the palatal root surface and a pointed buccal beak that adapts to the buccal root bifurcation. The #53R and #53L are similar but with a more pointed palatal beak and a straight handle. These forceps can apply an excessive amount of force and fracture the maxillary tuberosity if used improperly.

Mandibular Forceps

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses