The facelift procedure originated in the early part of the twentieth century and initially involved excising redundant skin with little to no subcutaneous undermining. In the 1920s surgeons began to employ subcutaneous undermining with subsequent excision and redraping of the skin flap. This became the preferred technique for several decades and was effective at improving skin laxity but failed to address the underlying ptotic soft tissues. Before this realization, surgeons attempted to improve on the subcutaneous approach by developing procedures addressing platysmal banding and submental lipomatosis. Subsequently surgeons realized that several factors are involved in aging along with increased skin redundancy, namely ptosis of the deep soft tissues, skeletal deformities, and changes in skin texture.

In 1974 Skoog introduced a technique to address deeper tissues by elevating a subdermal flap that was continuous with the subplatysmal plane in the neck. The skin and platysma are left as a single unit and elevated together to give the patient a more youthful jawline. Skoog’s technique did not gain wide acceptance but was a turning point in facelift surgery. In 1976, Mitz and Peyronie helped define the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). This study provided an anatomic basis for the dissection and manipulation of the SMAS, providing a longer lasting and more natural facial rejuvenation.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s multiple variations on Skoog’s technique were offered. Hamra introduced the deep plane rhytidectomy followed by the composite rhytidectomy in an attempt to improve the nasolabial and periorbital regions. Owsley added to this by describing the malar fat pad dissection and suspension to improve the nasolabial crease. Ramirez expanded on the work of Tessier and Psillakis to develop a subperiosteal rhytidectomy technique to improve the appearance of the cheek, forehead, jowls, lateral canthus, and eyebrows.

In general, four generations of rhytidectomy have been described ( Table 22-1 ). Although debate continues as to which technique is superior, various comparison studies have been unable to show a significant benefit from the more invasive third- and fourth-generation procedures over second-generation procedures. Proponents of the superficial plane techniques cite decreased risks, reduced complications, lower morbidity, decreased convalescence, and high patient satisfaction as advantages. On the other hand, proponents of the deep plane facelifts report more stable long-term results, better control of the midface, and similar risk and complication rates and convalescence as less invasive techniques. Kamer reported a decrease in need for secondary procedures from 30% to 11% in the first year after switching to deep plane lifts. Pastorek also reported a decrease in need for revisions from 10% to 2% with the deep plane facelifts. Wettstein and co-workers used laser surface scanning to assess facial symmetry in unilateral facelifts for reconstruction. In the future, this technology may allow for a more objective comparison of the superficial and deep plane techniques.

| I | Subcutaneous dissection only with variable skin undermining |

| II | Subcutaneous dissection + SMAS plication or imbrication |

| III | Subcutaneous dissection + SMAS plication or imbrication + deep midface section dissection |

| IV | Composite dissection |

Within the last decade the trend has been for reduced complexity in the facelift operation. In addition, patients are more demanding of shorter, less invasive procedures with limited convalescence. More patients are actively seeking cosmetic procedures at a younger age. To satisfy patient demands, less invasive midface lifts have been developed to improve the nasolabial region in combination with less extensive facelift procedures. Included in these advances are the minimal incision facelift surgery, suspension sutures, endoscopic techniques, and autogenous and synthetic filler materials. Discussion of these techniques is beyond the scope of this chapter.

PATIENT EVALUATION

Evaluation of the patient begins with a complete understanding of the desires of the patient in combination with what the surgeon feels will benefit the patient. In the end there must be a balance between the two to satisfy both parties ( Table 22-2 ). As with any surgical procedure, a thorough history and physical examination are required. These are important in assessing the patient’s fitness to undergo anesthesia and to discover any conditions that could affect the outcome of the procedure. Appropriate workup and consultations should be obtained for patients with cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, or hematologic disease. A list of current prescription and over-the-counter medications is also required. In particular, the use of agents that interfere with coagulation or platelet function should be determined, to reduce the potential for hematoma formation. Over-the-counter medications such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs), herbal preparations (ginseng, garlic, gingko), and high-dose vitamin E should also be discussed. The use of isotretinoin may have adverse effects on healing.

| Patient | Surgeon |

|---|---|

| Minimal morbidity risk | Safe and predictably consistent outcomes |

| Long-lasting results | Reasonable operative time |

| Quick recovery | Reasonable cost to patients |

| Affordable | Reasonable postoperative recovery period |

| Performed on outpatient basis patient will be ambulatory | Adaptable for revision procedures |

| Teachable to residents and fellows |

The social history is of critical importance in patients being evaluated for facelift surgery. Along with its effects on general health, there are multiple studies that show an increased risk of skin flap necrosis with smoking tobacco. Rees noted a 7.5% rate of skin slough in smokers, compared with 2.7% in nonsmokers. The use of illicit drugs, such as cocaine, cannot only affect the cardiovascular system but may contribute to skin necrosis and poor healing secondary to its effects on the microvasculature. Heavy alcohol use can adversely affect coagulation and also contribute to a decreased nutritional status and anemias that may reduce healing potential.

An anesthetic history is important for those practitioners who perform these procedures in their clinic with conscious sedation. Adverse reactions to certain medications including allergies as well as postoperative nausea and vomiting can be addressed by avoiding certain drugs or supplementing the patient with appropriate antiemetic medications intraoperatively and postoperatively. In patients with a history of uncontrolled gastroesophageal reflux disease, diabetic gastroparesis, or obesity, it would be reasonable to limit the patient to a clear liquid diet 24 hours before fasting (NPO). The use of proton pump inhibitors or histamine receptor antagonists along with a prokinetic agent such as metoclopramide can reduce the pH of stomach contents and facilitate gastric emptying.

The psychologic history can give the surgeon clues to the patient’s motivation for surgery as well as his or her expectations. Any patient whose mental condition does not seem to be controlled should be referred for counseling before surgery is scheduled. Some patients may be reluctant to report such a history. If a patient has had multiple procedures on the same body part without any obvious deformities, it should alert the surgeon to the possible diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder. Surgery on patients who seem to have unrealistic expectations should be postponed so that additional consultation with the surgeon and/or mental health professional can be scheduled to better explain the procedure and uncover any underlying emotional issues.

Before the head and neck examination, a general physical examination should be performed, concentrating on the cardiovascular, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and neurologic systems. Prior surgical incisions, especially for thyroidectomy or parotidectomy, are useful in determining how the patient is going to heal.

When evaluating the face it is useful to be aware of the structures involved in the natural process of aging. During the fifth decade of life, patients often notice sagging of skin in the jowls, prominent bands in the platysma, and a collection of submental fat. The severity of ptosis in these regions varies from patient to patient, but these are the areas most improved after a facelift. A systemic evaluation of the face will help the surgeon address each of these areas and determine if concomitant ancillary procedures are needed. This will also give the surgeon the opportunity to discuss with the patient exactly what is expected with regard to outcomes and limitations of the procedure.

Typically the face is divided into thirds. The upper one third includes the forehead and upper and lower eyelids. These areas are not typically addressed with the superficial plane rhytidectomy and are not discussed here. The middle facial one third includes the cheeks and ears. The amount of skin laxity in this area should be assessed and may affect the choice of incision. It should be noted whether the patient is thick-skinned or thin-skinned, as this may contribute to the rate of relapse and ease of tissue handling. Other pertinent findings include location of the temporal hairline, the presence of fine or course rhytids, and skin quality. Quality refers to the presence and severity of sun damage, along with the apparent elasticity of the skin. The earlobe is an important structure to evaluate, as there can be displacement of the lobule after closure. The patient should be made aware of any deviation from normalcy preoperatively. As previously mentioned, the nasolabial fold is an important structure associated with facial aging. As the malar fat pad sags inferiorly, the overlying skin follows, causing a deepening and lengthening of the nasolabial fold. Surgeons who advocate extended sub-SMAS facelifts claim this area is not adequately addressed with an SMAS plication or imbrication in association with a superficial plane facelift. It may be important to make the patient with a severe deformity in this region aware of this possible limitation if a superficial facelift procedure is chosen. The presence and degree of jowling should be noted. This is the result of sagging of the buccal fat and skin posterior to the mandibular retaining ligaments of the cheek. Finally, perioral rhytids should be noted as they are not correctable with the rhytidectomy.

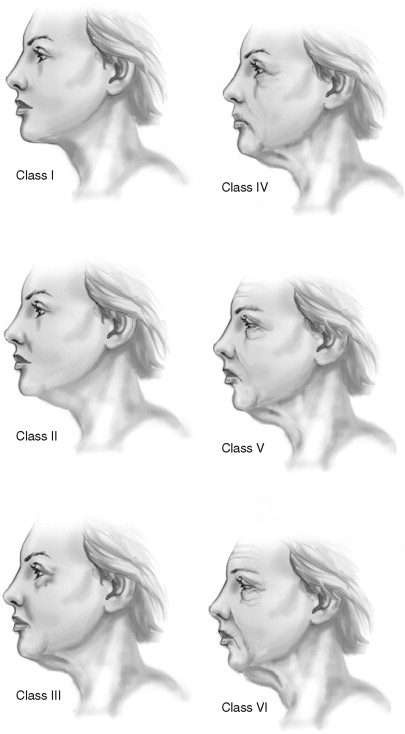

The lower facial one third includes the chin, jawline, and neck. Dedo divided profiles of the neck into six classes ( Table 22-3 ). This classification scheme may be used as an adjunct by the surgeon to determine the most effective way to improve the patient’s specific abnormality for optimum results ( Figure 22-1 ). Other factors to consider are the amount of skin redundancy, degree of platysmal banding, cervicomental angle, and submental fat accumulation. The youthful neck has a cervicomental angle of around 90 degrees. A hyoid bone that is located lower than the fourth cervical vertebrae can contribute to an obtuse angle. The submandibular glands should be evaluated for ptosis, as this is generally difficult to correct.

| Patient | Surgeon |

|---|---|

| I Normal |

|

| II Cervical skin laxity | Obtuse cervicomental angle due to relaxed skin |

| III Submental fat accumulation | Requires submental lipectomy |

| IV Platysma muscle banding | Requires muscle clipping, plication, or imbrication |

| V Retrognathia or microgenia | Requires genioplasty or orthognathic surgery |

| VI Low hyoid |

|

Preoperative photographs are vital for the patient’s records in terms of medicolegal documentation as well as being an aid for postoperative comparison. They also give the surgeon an opportunity to review the patient’s facial characteristics between the workup appointment and surgery. The standard photographs are usually taken using a light blue background with the head in the Frankfort horizontal position. The desired views include the full face in repose and smile, right and left lateral views, and right and left three-quarter views. Close-up views of the forehead, eyebrows, and periorbital and perioral regions should be taken as needed.

The conclusion of the preoperative visit should include education of the patient regarding the procedure and possible complications. Patients should be instructed to avoid wearing makeup on the day of surgery. The face and hair should be cleaned with germicidal agents the night before surgery. The need for preoperative antibiotics should be determined and prescriptions given. If the patient smokes, an attempt to quit 2 months before surgery is recommended. The patient may be given prescription medications such as varenicline (Chantix) or bupropion (Wellbutrin, Zyban) to aid in smoking cessation during this period. Nicotine replacement products such as patches should not be used at this time as their effect on healing has not been fully assessed. The patient should avoid vitamin E and NSAIDs or aspirin-containing medications at least 2 weeks before surgery. Postoperative instructions should be given verbally as well as written. Include the likely postoperative course in terms of amount of swelling and bruising to be expected.

The patient should allow a period of 10 to 14 days for sufficient resolution of ecchymosis, after which makeup can be used as camouflage until complete resolution occurs. Patients should expect not to return to work or social activities before this time. The patient should understand that during the early postoperative period there will be some degree of residual edema and that the final results will not be achieved until a period of several months. Patients who are not familiar with the slow evolution of these results may quickly become frustrated.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

For the purpose of this chapter, emphasis will be on the most commonly performed facelift procedure, the superficial plane rhytidectomy. Most surgeons prefer to use local anesthesia combined with conscious sedation or general anesthesia. Most patients are able to tolerate this procedure alone or in combination with additional procedures such as blepharoplasty.

While the patient is in the seated position, the desired areas of undermining are marked. The hair should be bound and positioned away from the surgical field. The usual antiseptic scrub for head and neck operations is acceptable, starting at the clavicles and covering the face. It is important to include the scalp around the forehead and temporal regions as well as the postauricular areas.

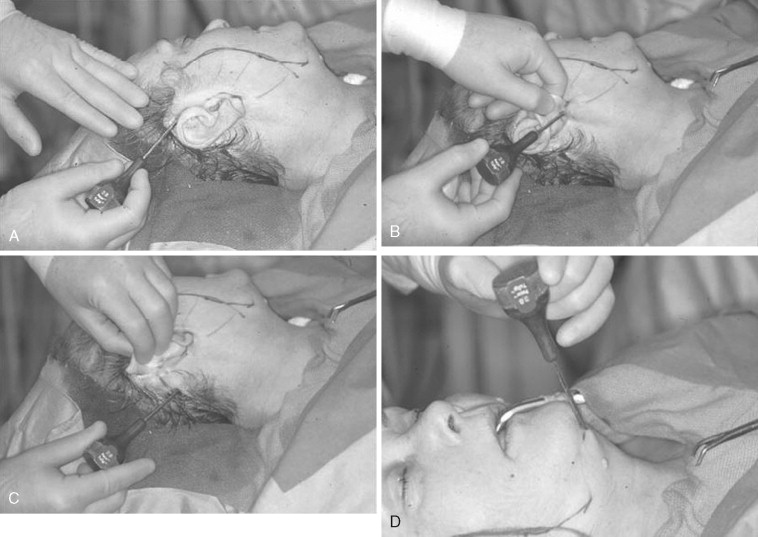

Local anesthesia is infiltrated along the incision line using an aspirating dental syringe and 2% lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine. The remainder of the anesthesia is provided in the tumescent solution. The use of a tumescent solution was initially described for use in liposuction and was applied for use in facelifts. The tumescent technique serves several purposes including local anesthesia, establishment of an initial subcutaneous dissection plane, and hemostasis. This technique has been described by many authors, and the composition of the solution differs by surgeon’s preference. Our preference is a mixture of 20 mL of 2% lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine with 180 mL of normal saline (0.2% lidocaine with 1 : 1,000,000 epinephrine concentration). This solution is delivered through four trocar sites: temporal, infralobular, mastoid, and submental ( Figure 22-2 ). An effort is made to deposit the mixture via a cannula system in a subcutaneous plane superficial to the SMAS and platysma muscle. The tumescent solution should be delivered 1 cm beyond the proposed extents of flap undermining. This will usually require around 75 mL on each side of the face and an additional 50 mL in the submental region. The submental region is first followed by one of the sides, with the contralateral side being done just before closure of the initial side. The solution requires 8 min for maximum effect. The blunt cannula is combined with suction for the initial dissection and any indicated liposuction of the submental and neck region ( Figure 22-3 ). After this, the facial dissection is carried out in a similar fashion using the blunt cannula dissection without suction ( Figure 22-4 ).

The incision for the standard facelift should be marked before any infiltration and while the patient is in the seated position. Several modifications have been proposed; however, there are certain principles to which the surgeon should adhere when planning any incision. Although it is not necessary to shave the hair, the incision should be parallel to the hairline and should not extend more than 2 cm within the temporal hair tuft. Some surgeons recommend a pretrichial incision in this area to avoid a posterosuperior repositioning of the temporal hairline. The incision is extended inferiorly to the root of the helix and curves anteriorly around the crus helicis. As the tragus is encountered, the incision can be directed in a pretragal or posttragal direction. The pretragal incision is preferred in order to stay anterior to the base of the incisura intertragica ( Figure 22-5 ). Doing so prevents distortion the tragus during closure. The incision is continued, paralleling the anterior lobule and dipping 1 to 2 mm below the inferior junction of the lobule and the skin of the cheek to help avoid earlobe deformities (elfin, batwing, pixie). Posterior to the ear the incision is continued in a superior direction 4 to 5 mm onto the conchal bowl to the level of the postauricular sulcus or the superior crus of the antihelix. The incision is then curved posteriorly into the retromastoid scalp ( Figure 22-6 ). In cases of excessive cervical redundancy, the retromastoid extension can be made to parallel the hairline for several centimeters before entering hair-bearing skin in order to prevent a step-off deformity. This is more important in individuals with short hair. To maximize cervical pull in this areas some authors recommend curving the posterior aspect of the incision to be roughly perpendicular to a line paralleling the inferior border of the mandible. It is also advisable to maintain an approximate 90-degree angle at the reflection of the posterior flap to help reduce skin slough at the tip.

In the male patient, consideration must be given to hair pattern, such as balding, sideburns, or short hair. It is important to realize these differences because of the increasing number of male patients requesting these procedures. For patients with thinning hair or male pattern baldness, the temporal extension is most important and requires modification. The sideburn is managed by placing the preauricular portion of the incision in a natural skin crease paralleling the sideburn ( Figure 22-7 ). The incision should preserve at least 2 mm of non–hair-bearing skin anterior to the ear to maintain a natural appearance and prevent the transposition of hair into the external auditory canal. This is opposed to the traditional curved incision used in women. As described earlier, placement of the posterior extension of the incision adjacent and parallel to the hairline is crucial for avoiding a step-off deformity that cannot be easily camouflaged with short hair styles. It should also be recognized that hair may also be transferred from the beard into the postauricular region.

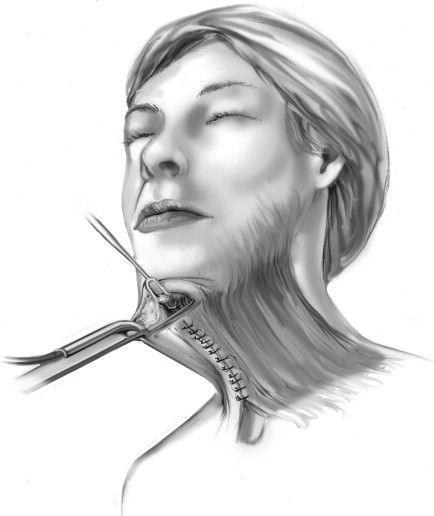

Management of the cervical region is done with a combination of liposuction, lipectomy, and platysmal manipulation. Once the tumescent solution has been administered, liposuction of the submental region is accomplished with wall suction and cannula. Subsequently an incision is made in the submental skin crease as an extension of the initial trocar incision. The location of this incision in “double-chinned” individuals should not be made in the prominent crease, but slightly inferior to limit any noticeable scar contracture that may accentuate the crease. After a 2-cm incision is made, a subcutaneous (supraplatysmal) plane is dissected using facelift scissors. This plane will join the subcutaneous plane in the lateral cervical regions of the neck, which are dissected later. Conservative lipectomy may be done at this time. The surgeon must be cautious because of the possibility of excessive fat removal, especially in the subplatysmal plane, which could result in an overly thinned, atrophic neck or “cobra” neck deformity. The anterior platysma bands are identified and are undermined to the level of the thyroid cartilage inferiorly. The medial aspect of the platysma on either side is repositioned at the midline, and the excess intervening tissue is excised. The plication or imbrication of the remaining tissue is performed using a 2-0 slow resorbing suture ( Figure 22-8 ). Occasionally a partial or complete horizontal release of the platysma will be required to better define the cervicomental angle and release excess tension caused by the platysmal manipulation. This is done using scissors, starting at the midline or the most inferior aspect of the platysmal undermining. If a complete resection is required, the lateral myotomy may be done through the lateral neck facelift flap.

Flap development in the cheek is performed subsequent to blunt cannula dissection and is initiated by undermining 1 cm along the entire length of the incision. This is done in a subcutaneous plane using either scissors or a blade ( Figure 22-9 ). Skin hooks are helpful for retraction with tension on the flap directed perpendicular to the skin of the face. The subcutaneous layer should be of adequate thickness (3 to 4 mm) to preserve the blood supply of the flap. In the temporal region, defined as the area above the zygomatic arch, the depth of the flap should be deep to the temporoparietal fascia. This fascia is an extension of the galea, and a plane of loose areola tissue can easily be found. Deep to this is the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia. The purpose for maintaining this depth is to provide increased tissue thickness to protect and support the overlying hair follicles and prevent alopecia. A combination of blunt and sharp dissection is used to extend the undermining anteriorly. The flap reflection continues with removal of tissue bridges interposed between the residual tunnels created as a result of the previous subcutaneous blunt cannula dissection ( Figure 22-10 ). A push and cut motion with the facelift scissors is generally used. This sub-SMAS dissection may be safely extended to the lateral canthus without fear of damaging the facial nerve. Rees T-clamps can aid the dissection by placing gentle countertraction on the flap. The transition from the temporal dissection to the cheek dissection is accompanied by a change from the subtemporoparietal (sub-SMAS) plane to a subcutaneous plane. This acts to protect the frontal branch of the facial nerve as it crosses over the zygomatic arch. The frontal branch of the facial nerve is located anterior and inferior to the frontal branch of the superficial temporal artery, so preservation of this artery helps to protect the nerve. In the sagittal plane it crosses the arch at a variable distance of 8 mm to 35 mm anterior to the external auditory canal. This transition should occur above the arch owing to the more superficial location of the nerve as it crosses the zygoma.

The extent of undermining is variable from one patient to another and is based on experience. Four to 5 cm may be adequate for younger patients with less laxity, versus extending the dissection to within 1 cm of the oral commissure in older patients with more significant skin redundancy and jowling. When platysma banding is present, the cervical dissection should be carried to the level of the thyroid cartilage and should communicate with the dissection from the contralateral side.

In the postauricular region, dissection is once again in the subcutaneous plane. This is especially important below the earlobe, where the great auricular nerve is located. This is the most commonly injured nerve during facelifts, with an incidence of permanent injury around 5%. The nerve is known to be located just beneath the superficial fascia in the neck. The nerve trunk can reliably be found 6.5 cm inferior to the caudal edge of the external auditory canal at the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Erb’s point). During surgery, with the patient’s head turned to one side, the sternocleidomastoid muscle may become tensed, bringing the nerve even closer to the surface. Above the level of the earlobe there is little danger of damaging this nerve, and the dissection may be carried deeper. Meticulous hemostasis should be maintained with bipolar electrocautery throughout the procedure. Judicious use of electrocautery on the flap side is advised to reduce the risk of ischemic injury and flap necrosis.

After the skin flap has been adequately undermined, manipulation of the SMAS in the region of the cheek is addressed. SMAS manipulation is important in addressing the ptotic fat of the cheek and jowls. This does not have a great effect on midface structures such as the melolabial fold, orbicularis oculi, or the forehead. Nevertheless, repositioning of this tissue and the skin flap in independent bidirectional vectors has the effect of providing long-lasting results. As discussed earlier, multiple comparison studies have been reported in the literature, with none showing any conclusive advantage of the deep plane and composite facelifts over the superficial plane facelift with SMAS manipulation.

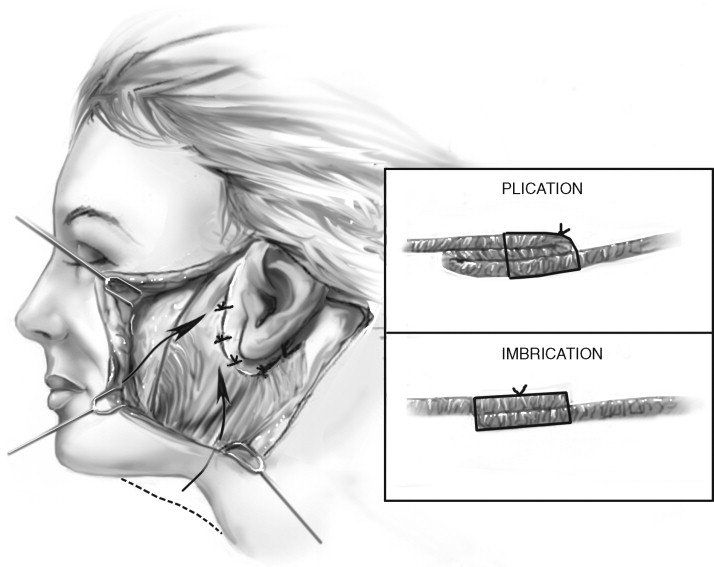

Manipulation of the SMAS is accomplished by plication, imbrication, or a combination of both. Plication involves folding the SMAS on itself to achieve the desired repositioning, and imbrication involves an incision or excision of the SMAS to allow overlapping of the distal portion over the proximal portion in the desired position ( Figure 22-11 ).

Both techniques may be accomplished using 2-0 slow resorbing suture on a 2-0 tapered needle. The sutures are placed in a buried fashion to prevent temporary palpability or irritation of the skin flap. The first plication suture is placed in the area of SMAS overlying the angle of the mandible, which is then secured to the fascia immediately inferior and medial to the tragus ( Figure 22-12 ). A second suture is placed in the fascia at a level lateral to the oral commissure and secured immediately superior to the tragus. Additional sutures may be placed in the preauricular and postauricular areas as needed. These sutures should be placed under moderate tension in order to achieve the desired amount of tightening in a posterosuperior direction.

Imbrication involves incising and/or excising a portion of the SMAS and may require the development of a sub-SMAS flap in some cases. Techniques have been developed to elevate a flap that extends to the nasolabial fold during deeper plane facelifts.

The typical dissection begins with a vertical incision of the superficial fascia approximately 1 cm anterior to the ear. The fascia is grasped with pickups, and tissue is excised, producing a gap anteroposteriorly from just below the zygoma to midparotid ( Figure 22-13 ). No sub-SMAS elevation is done, and the flap is repositioned in a posterosuperior direction and secured at similar levels as described for the plication technique. Before completion of the first side, the contralateral area of the face is infiltrated with both the local anesthetic and tumescent solution.

After the first side has been completed, the head is placed in a neutral position and redraping of the skin flap is performed. The neck must not be flexed or extended, as this will affect the amount of skin excised and result in a less than ideal outcome. It is important to close this flap under minimal tension to minimize the scar width and reduce the likelihood of skin flap necrosis. The vector of pull is primarily in a posterior direction with a small superior component. Before the skin flap is trimmed, staples are placed in key areas. This allows the surgeon to choose the most advantageous flap position that avoids misdirecting facial rhytids or distorting the temporal hairline. The first key staple is placed in the temporal region just above the ear. The second staple is placed in the postauricular region at the most posterior superior aspect of the flap. Careful attention should be given to the proper inset of the ear ( Figure 22-14 ). The long axis of the earlobe is 10 to 15 degrees posterior to the long axis of the ear proper in the nonoperated ear. Significant deviation will result in an unnatural appearance. After proper positioning, the skin flap is trimmed using a scalpel or iris scissors.

Skin closure in the hair-bearing scalp (i.e., temporal and mastoid regions) is performed with subdermal 3-0 resorbable sutures and skin staples to minimize the tension on the superficial skin layer. The postauricular region is closed with a running 4-0 plain gut suture without a deep layer. In the preauricular region, a deep layer of 4-0 resorbable suture is followed by skin closure with a 6-0 or 7-0 running nonresorbable suture. The opposite side of the facelift is accomplished at this time in an identical fashion. The submental incision is the last area closed, in a similar fashion to the preauricular region. Any minor amount of residual fluid is expressed submentally before closure. No drains are placed.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses