Introduction

The aim of this study was to determine how sensitive dental specialists and laypeople are to maxillary incisor crowding when viewed from the front.

Methods

Computer technology was used to create a series of photographs of the incisors of a smiling woman viewed from the front. The photographs showed varying degrees of maxillary incisor crowding classified according to Little’s irregularity index (LII). The incisors illustrated in the photos were ranked on a scale from perfect alignment to severely crowded. The rating was done by 4 groups of people: orthodontists, general dentists, laypeople with experience of orthodontic treatment, and laypeople with no history of orthodontic treatment.

Results

The orthodontists and the general dentists noted misalignment of 1 central incisor when the LII reached 1.5 mm, whereas the laypeople with or without experience of orthodontic treatment were sensitive to 2.0 mm of crowding. When the LII reached 2.0 mm for 1 lateral incisor, it triggered the orthodontists to consider providing orthodontic treatment, whereas this degree of irregularity was ignored by the general dentists and laypeople. When both central incisors were misaligned, the orthodontists were sensitive to the fact at 2.0 mm of LII, whereas the general dentists and the laypeople with experience of orthodontic treatment became sensitive at 3.0 mm of LII, and the laypeople with no history of orthodontic treatment were sensitive at 4.0 mm of LII. When both lateral incisors were misaligned, the orthodontists noted the crowding at an LII of 3.0 mm, the general dentists became sensitive at an LII of 4.0 mm, whereas both the laypeople with experience of orthodontic treatment and the laypeople with no history of orthodontic treatment ignored it. When the crowding of all maxillary incisors reached an LII of 4 mm, both the orthodontists and the general dentists were alerted to the fact, but both the laypeople with experience of orthodontic treatment and the laypeople with no history of orthodontic treatment were sensitive only to a total incisor crowding equal to an LII of 6.0 mm.

Conclusions

Orthodontists are more critical than other groups when evaluating the misalignment of the maxillary incisors. It appears that the central incisors play a more important role than do the lateral incisors when dental crowding impacts smile esthetics. For all observer groups, it also appears that people are more sensitive to the misalignment of a single tooth than they are to the same level of crowding distributed over multiple teeth.

Highlights

- •

No study has tested the sensitivity of orthodontists and others to maxillary incisor crowding.

- •

We tested at what level of incisor crowding orthodontists and others begin to recognize the problem.

- •

Orthodontists are more critical than others when evaluating misalignment of maxillary incisors.

- •

Central incisors are more important than laterals in dental crowding smile esthetics.

- •

A single tooth misalignment is more noticeable than crowding distributed over many teeth.

Smiles are important in interpersonal communications; in this role, they are usually associated with pleasant thoughts and events. At the same time, the esthetic quality of a smile also plays a major role in defining facial beauty and harmony. The arrangement of the incisors is closely associated with smile excellence, and it is thus unfortunate that the arrangement of the incisors is often not in harmony with the rest of the facial features. In this sense, incisor crowding is a common trait of malocclusion and will influence not only the facial esthetics, but also the social appeal of a person. Because they are so visible, it is likely that the maxillary incisors play a greater role than do the mandibular incisors in defining the attractiveness of a smile.

It has been said that the trained eye readily detects what is asymmetric and out of harmony with its environment. It is believed that not all people are equally sensitive to specific dental aberrations and, accordingly, that orthodontists are the most, general dentists less, and laypersons the least observant of altered dental esthetics.

Previous research dealing with smile esthetics has focused on buccal corridor spaces, gingival anatomy, smile arcs, maxillary incisor proportions, and mandibular crowding. At least 1 earlier study evaluated the perceptions of orthodontists and laypeople with respect to varying degrees of mandibular incisor crowding as measured with Little’s irregularity index (LII). It would appear that orthodontists are more critical than other groups when evaluating the misalignment of the mandibular incisors as judged from an occlusal view. To date, there does not seem to be a study that has tested the sensitivity of orthodontists and others to maxillary incisor crowding as measured with the LII.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine at what level of maxillary anterior crowding orthodontists and laypeople begin to recognize the problem as viewed from the front of patients. Flowing from this is the question: how much dental crowding is the general public willing to accept without requesting orthodontic treatment?

Material and methods

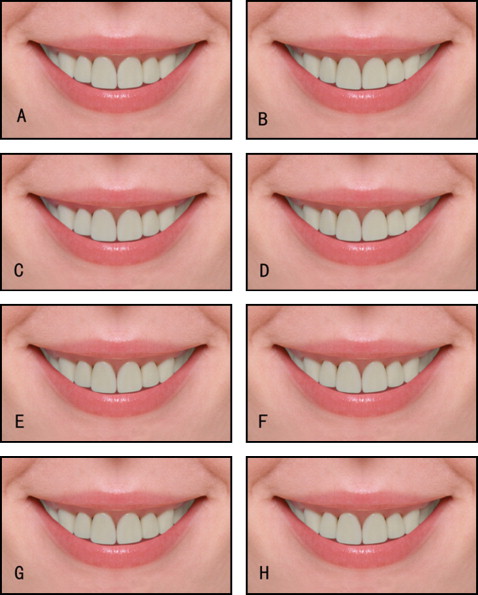

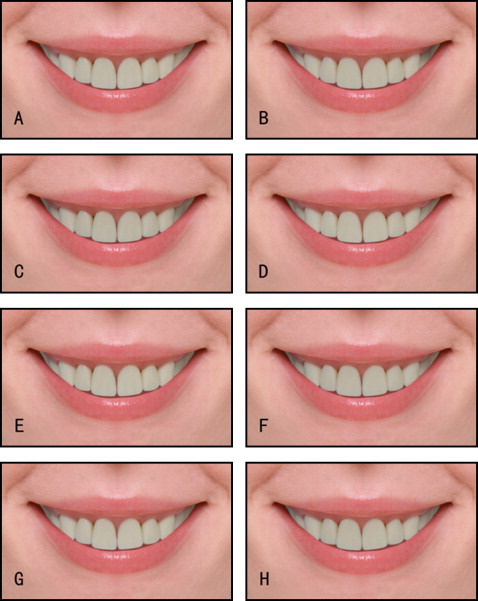

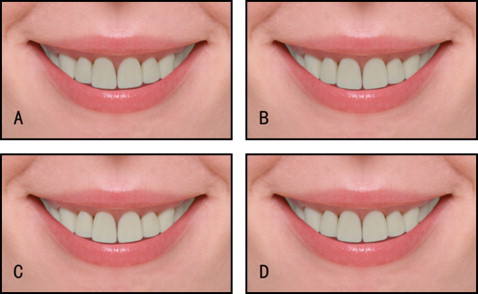

The study was based on a series of photographs that were selected for specific characteristics and were then modified with computer manipulations. The dental images of the maxillary arch were obtained from a typodont (Nissin, Kyoto, Japan). The photographs of the original typodont with well-aligned incisors, as well as the same typodont with teeth set to various degrees of crowding, were taken under the same lighting conditions and by the same photographer (W.M.) using the same camera array (NEX5R; Sony, Tokyo, Japan). To achieve varying degrees of dental misalignment of the maxillary incisors, the crowns of these teeth were rotated according to a specific sequence of changes on the typodont. First the lateral incisors were moved, then the central incisors were moved, and then combinations of central and lateral incisors were moved. Each time, only 1 parameter was changed. Specifically, to simulate crowding, the respective teeth were rotated along the axis that was as close as possible to its estimated central long axis on the typodont. Each tooth (maxillary central or lateral incisor) was rotated in turn as required to produce an LII value of between 0.5 and 2.0 mm for that tooth. During these simulations, a total LII value of 0.5 mm was achieved by an equal amount of rotation of 0.25 mm at the mesial and distal aspects of the specific tooth. The movement of the teeth was measured with a digital Vernier caliper (Fred V. Fowler, Newton, Mass).

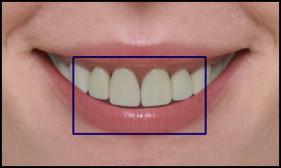

A front view photograph of a smiling white woman was selected for this study. The teeth, tongue, nose, and chin were removed from the original photograph to eliminate facial features that could have acted as confounding variables. Each subsequent frontal image obtained from the various typodont setups of the incisor teeth was then morphed (version 7.0, Adobe Photoshop CS; Adobe Systems, San Jose, Calif) to replace the teeth that were removed from the original photograph ( Fig 1 ). A total of 20 photographs with different degrees of misalignment of the maxillary anterior teeth were taken ( Figs 2-4 ). From the 20 photographs, 4 ( Figs 2 , G ; 3 , C and H ; and 4 , A ) were selected randomly for duplication to assess participant reliability. Therefore, a total of 25 photographs (1 ideal, 20 altered, and 4 duplicates) were given to each rater who took part in this study. The order of all photographs was randomized using randomizer software ( www.Randomizer.com ). Inconsistent ratings of duplicate images led to the exclusion of those raters from the study.

Four groups of evaluators (raters) participated in this study: orthodontists (ORT), general dentists (GD), laypeople with experience of prior orthodontic treatment (LWO), and laypeople with no past history of orthodontic treatment (LNO). The clinician evaluators were selected in order of appearance in 2 registers of professionals. The lay evaluators were provided by a commercial firm (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, Calif).

An Internet Web page was used to conduct the survey. Each respondent was asked to consent to participating in the study and to complete a questionnaire asking for personal data such as age, sex, educational background, and history of orthodontic treatment. Upon completion of the questionnaire, a photograph was displayed with an ideal alignment of the maxillary anterior teeth. The teeth under review were identified with a blue box to define the area that the participant was expected to observe ( Fig 1 ). In the subsequent photographs for scoring, the blue box did not appear to minimize distraction during scoring of the pictures. The computer images were shown about twice life size and in high definition. The lighting of the teeth was from the front, and all maxillary teeth were well lit while maintaining sufficient contrast to allow irregularities of the teeth to be visible.

Each following page of the Web screen displayed only 1 front-view photograph of either the ideal or the altered pictures ( Figs 1-4 ) with a scale of 1 to 5 for scoring. The participants were asked to choose a score from 1 to 5 for each picture on each page, with 1 representing the worst incisor irregularity and 5 the best incisor alignment. A score of 3 or less was considered to indicate a level of incisor crowding that was unacceptable.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using a series of parametric and nonparametric statistics with a software program (SPSS version 12.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, Ill). All tests were performed at the 5% level of significance. Intraexaminer reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic. Within each group, 1-way repeated measures analysis of variance tests were conducted to assess how the groups rated each level of misalignment. In addition, the Student t test was used to examine intergroup differences in the LII.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using a series of parametric and nonparametric statistics with a software program (SPSS version 12.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, Ill). All tests were performed at the 5% level of significance. Intraexaminer reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic. Within each group, 1-way repeated measures analysis of variance tests were conducted to assess how the groups rated each level of misalignment. In addition, the Student t test was used to examine intergroup differences in the LII.

Results

A total of 210 evaluators participated in the study and started the survey; however, 97 of them were excluded because they did not complete the survey, or their answers regarding the 4 duplicate photos were inconsistent. The remaining 113 participants were then classified into the 4 predetermined groups according to their dental background ( Table I ). The evaluators consisted of 44.2% men and 56.8% women. Their age distribution was as follows: 72.6% were 19 to 30 years old, 16.8% were 31 to 44 years old, and the remaining 10.6% were either older than 44 years or younger than 19 years old.

| Group | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| ORT | 28 |

| GD | 25 |

| LWO | 31 |

| LNO | 29 |

The results of the kappa statistic for the 4 duplicate photographs showed intraexaminer reliability values of 0.65, 0.53, 0.77, and 0.82, respectively, which demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability.

Table II shows the rating scores of all 4 groups at different values of LII. When the LII value was 1.5 mm for 1 central incisor, the mean score of the ORT was 2.86 ± 0.17, and the score of the GD was 2.92 ± 0.18. These values were below (unacceptable alignment) the preset critical score of 3. When the LII score reached 2.0 mm, the LWO and the LNO had scores of 2.68 ± 0.18 and 2.79 ± 0.16, respectively. The groups mostly agreed on their estimates of alignment for 1 incisor in the ranges of the LII tested.