At present no process is in place in the United States to comprehensively monitor the national burden of oral diseases from the perspective of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), yet available evidence shows that a substantial percentage of the adult population rates their oral health poorly. This article reviews applications of OHRQoL in dental public health. The authors specifically review its use, contributions, and needed advances in: (1) monitoring the impacts of oral diseases on OHRQoL at the national level, and in public health surveillance at the state and local levels; (2) treatment outcomes research and program evaluation; and (3) clinical practice.

The twentieth century was noteworthy in dentistry for the many epidemiologic advances that occurred in the study of oral diseases and conditions. A largely biologic perspective to these epidemiologic studies contributed a wealth of valuable information about the burden of oral diseases, how it has changed over time, and its distribution among the population according to important demographic and social characteristics. Major advances have likewise been made in the prevention and treatment of many oral diseases, and their effects on reducing the disease burden is both observable and pronounced. For adults, the prevalence of dental caries, periodontal diseases, and tooth loss declined in the 1990s, with major improvements occurring for some conditions among black nonHispanics and Mexican Americans. Yet conditions worsened for pre-school aged children and major disparities remain in almost all disease indicators .

Despite their enormous contributions, these biologic assessments of disease do not provide a complete picture of the burden that oral diseases pose for society because they do not measure the full impact of disease and its treatment on well being. According to the United States Surgeon General, oral diseases and conditions can “…undermine self-image and self-esteem, discourage normal social interaction, cause other health problems, and lead to chronic stress and depression as well as incur great financial cost. They may also interfere with vital functions such as breathing, food selection, eating, swallowing, and speaking and with activities of daily living such as work, school, and family interactions” . The importance that some organizations in the United States place on the impact of oral diseases on the overall health and well-being of Americans is illustrated by excerpts from a number of documents, displayed in Table 1 .

| Healthy People 2010 | 1 st of 3 overall goals: To help individuals of all ages increase life expectancy and improve their quality of life. |

| Millions of people in the United States experience dental caries, periodontal diseases, and cleft lip and cleft palate, resulting in needless pain and suffering; difficulty in speaking, chewing, and swallowing; increased costs of care; loss of self-esteem; decreased economic productivity through lost work and school days; and, in extreme cases, death. Poor oral health and untreated oral diseases and conditions can have a significant impact on quality of life. | |

| Surgeon General’s National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health | …people care about their oral health, are able to articulate the problems they face, and can devise ingenious solutions to resolve them—often through creative partnerships. Ultimately, the measure of success for any of these actions will be the degree to which individuals and communities—the people of the nation itself—gain in overall health and well-being. |

| The Face of a Child: Surgeon General’s Workshop and Conference on Children and Oral Health | Children’s oral health is important to their overall health and well-being. Dental and oral disorders can have a profound impact on children. These include the effects on growth, school attendance, medical complications of untreated oral disease, and economic/social outcomes. |

| Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors Guidelines State and Territorial Oral Health Programs | Despite the fact that safe and effective means of maintaining oral health have benefited the majority of Americans, many still experience needless pain and suffering, have oral diseases that impact their overall health and well-being, and have financial and social costs that diminish their quality of life and burden society. |

| Centers of Disease Control Burden of Oral Disease Tool for Use by States | More than any other body part, the face bears the stamp of individual identity. Attractiveness has an important effect on psychologic development and social relationships. Considering the importance of the mouth and teeth in verbal and nonverbal communication, diseases that disrupt their functions are likely to damage self-image and alter the ability to sustain and build social relationships. The social functions of individuals encompass a variety of roles, from intimate interpersonal contacts to participation in social or community activities, including employment. Dental disease and disorders can interfere with these social roles at any or all levels. Perhaps due to social embarrassment or functional problems, people with oral conditions may avoid conversation or laughing, smiling, or other nonverbal expressions that show their mouth and teeth. |

| National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Strategic Plan | Goal 7, Objective 2: Assess the social, educational and economic impact of oral, dental and craniofacial diseases, disorders, conditions, and birth defects. |

A person usually thinks of his or her own health more broadly than whether they have a particular disease or not, a perspective suggested by the often observed weak statistical relationship between a person’s clinical disease status and their perceptions of their own health . At the population level, although most biologic measures of oral health status among adults in the United States improved during the 1990s, the percentage reporting the condition of their teeth or mouth as being “excellent or very good” declined . Furthermore, major cultural and sociodemographic shifts in North American society will continue to shape the way people think about their oral health experiences. For example, the number of public school students in the United States who are low-income is approaching a majority, standing at 46% in the 2006 to 2007 school year, and already has become a majority (54%) in the South . Poverty, poor education, and inequality not only result in poor oral health but also affect the way in which people think about their oral health.

Patient perceptions can be particularly important in oral health where different treatment or prevention strategies can demonstrate small differences in outcomes, where some benefits may be mostly psychologic, and where some people might not see a particular advantage to different types of treatment. People’s perspectives of the ways in which oral diseases, conditions, and treatments affect their symptoms, function and well being are referred to as oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). OHRQoL is one aspect of individuals’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and a complete separation of OHRQoL and HRQoL is not possible because oral health is one aspect of overall health. Thus, issues related to one’s overall HRQoL are relevant to those related to OHRQoL and vice versa.

The purpose of this article is threefold. First, it reviews the relevance of OHRQoL to public health and its use in public health practice, particularly for monitoring the impacts of oral diseases on quality of life at the national level, and in public health surveillance of oral disease burdens at the state and local levels. Second, it reviews the emerging use of OHRQoL in treatment-outcomes research and program evaluation. Finally, the authors briefly discuss the use of QHRQoL assessments in clinical practice and arguments for expanding their use in these settings, an area virtually undeveloped in dentistry. This review is framed by definitions of “patient reported outcomes” and how OHRQoL and its measurement fit within this frame of reference . Because of this perspective, discussed in the section titled “Defining oral health-related quality of life,” the authors do not include several categories of patient- or population-reported outcomes, such as individuals’ perceptions of their treatment needs or quality of their dental care. This article also takes a North American perspective for its review, particularly in the section addressing the first purpose of the paper.

Since Cohen and Jago first called for the development of patient-based measures for the psycho-social impact of oral health problems, the literature dealing with “quality of life” in “oral health” has grown substantially. The growth during the current decade has been particularly rapid. A Medline search crossing these two terms yielded 618 English-language citations, beginning with the first publications in the 1970s through early November 2007. Seventy-eight percent of these publications occurred in 2000 or after, 18% in the 1990s, and less than 4% before 1990. For purposes of this paper, the authors have made no attempt to conduct a systematic review of the areas that are its focus. Consequently, unknown biases might be reflected in some of the discussions and conclusions.

Defining oral health-related quality of life

Defining oral health-related quality of life is difficult because the concept is illusive and abstract, multidimensional without clear demarcations of its different components, subjective and personal, individually dynamic, and evolving within and across population groups as culture and societal expectations change . Locker further concludes that anyone who tackles this task is faced with interpreting many concepts, theories, terms, operational definitions, and resulting measurement instruments that have their theoretic and empiric roots in an almost overwhelming number of publications in the medical literature. Nevertheless, several excellent articles have explored the conceptual and theoretic developments of OHRQoL and laid the foundation for the relative explosion of OHRQoL publications since 2000 .

Because of its complexity, no standard definition of OHRQoL exists and it may be unwise to pursue one, although research in the area needs sound conceptual and theoretic underpinnings. Because of the challenges in defining the term, many have turned to operational definitions in which possible domains are simply listed, sometimes linked to conceptual models, such as that of the World Health Organization (WHO) model of health . For example, OHRQoL was defined in the Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health as a “…multidimensional construct that reflects (among other things) people’s comfort when eating, sleeping, and engaging in social interaction; their self-esteem; and their satisfaction with respect to their oral health” . The most widely used OHRQoL instrument, the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP), is based on Locker’s adaptation of the WHO model, in which impacts of disease are categorized in a hierarchy ranging from symptoms primarily internal to the individual (represented in the dimension of functional limitation) to handicaps that affect social roles, such as work . The domains in the OHIP include functional limitation (eg, difficulty chewing), physical pain (eg, sensitivity of teeth), psychologic discomfort (eg, self-consciousness), physical disability (eg, changes to diet), psychologic disability (eg, reduced ability to concentrate), social disability (eg, avoiding social interaction), and handicap (eg, being unable to work productively).

While no consensus definition exists for OHRQoL, experts agree about a number of its characteristics. Points of agreement from the perspective of two cancer researchers were recently reviewed in a text devoted entirely to OHRQoL . They concluded that HRQoL includes: (1) a perception of one’s life circumstances; (2) components that are both affective (ie, perceived pleasantness or unpleasantness of a situation) and cognitive (ie, appraisals, thoughts, and perceived satisfaction with the situation); (3) positive and negative aspects of an experience; (4) multiple, overlapping, and related domains of functioning, as reflected in the definition provided in the Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health; and (5) changes in individuals’ perceptions of HRQoL over time.

Patient- and population-reported outcomes and OHRQoL

Because OHRQoL represents a personal experience and, therefore, it most appropriately is reported by individuals themselves, confusion can exist about which self-reported oral health outcomes might qualify as OHRQoL measures. Self-reported health or treatment outcome measures can vary in complexity from a single-item question about some single concept (eg, presence or absence of pain or satisfaction with a particular type of treatment) to multi-item instruments measuring several domains of health status or treatment outcomes (eg, single scales measuring a specific functional outcome, such as chewing ability, or multidimensional scales, such as the OHIP instrument with its multiple domains and related items). The anatomic and physiologic complexity of the oral cavity, the many different diseases affecting this area of the body and the numerous available treatments for them, and the many resulting symptoms and functional outcomes resulting from both diseases and treatment can result in a particularly broad array of self-reported outcomes. Some practical guidance about OHRQoL is therefore needed in any review of its application. For this guidance the authors turn to clinical trials research, particularly cancer intervention trials.

The large number of self-reported health outcomes being used in intervention clinical trials are now being referred to as “patient-reported outcomes” (PRO) . In a recent draft guidance for industry to use in product-labeling claims, the Food and Drug Administration defined a PRO measurement as “…any aspect of a patient’s health status that comes directly from the patient (ie, without the interpretation of the patient’s responses by a physician or anyone else)” and may include reports of disease symptoms, treatment adverse effects, functional status, or overall well being .

A work group on measurement of cancer outcomes at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), after review of hundreds of applications of HRQoL, concluded that the features of HRQoL measures that distinguish them from PRO measures are that they are not only patient reported, but involve the patient’s subjective assessment or evaluation of important aspects of his or her well being . The implication of this distinction provided by the NCI work group is that all HRQoL measures can be classified as PRO measures, but there are PRO measures that have little or no evaluation component and, thus, would not quality as HRQoL measures. For example, the report of presence or absence of pain by someone would not quality as a HRQoL measure according to the NCI work group recommendations unless it included a personal assessment of its severity, bother, or other impact on some aspect of well being. Specifically, the NCI work group defined a HRQoL measure to include patient assessments of symptom impact, functional status, or global well-being.

The authors use these distinguishing characteristics of HRQoL provided by the NCI work group and others to guide this review of applications of OHRQoL in public health dentistry. As noted in the introduction, some PRO measures, such as satisfaction with treatment or the process of dental care itself, are not included in this article. The authors also extend the use of this term, which has its origins primarily in the clinical trials literature to public health, and thus refer to “population-” reported outcomes when discussing population-based surveys and other population-based OHRQoL applications. Use of the term “patient-” reported outcomes is limited to applications in clinical settings.

Application of OHRQoL in public health practice

The importance of oral health in people’s quality of life is a well ingrained, but to date a largely implied perspective, in the philosophy, goals, and strategies for dental public health practice (see Table 1 ). The three core functions of public health practice necessary for population health, articulated by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the future of public health and the associated 14 essential dental public health services related to these that were provided by the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) , are designed to identify and monitor oral health problems in populations and ensure that effective polices and programs are in place to help alleviate these problems. OHRQoL is at the core of the framework and definition for public health practice provided by the IOM and ASTDD documents.

Yet, attention to this aspect of oral health status remains largely at the conceptual level, with less attention having been given to its application to dental public health activities, such as the measurement of OHRQoL in state and local surveillance and population-based surveys, population screening programs to identify those needing referral and treatment, or the evaluation of how the implementation of public health programs affects OHRQoL, a point to be discussed in this article. At present, no data collection mechanism or process is in place in the United States to comprehensively monitor the national burden of oral diseases from the perspective of OHRQoL. This deficit is particularly important because one of the two Healthy People 2010 goals for the nation is to improve quality of life . The next two sections review use of OHRQoL measures in periodic national surveys and ongoing surveillance of oral health.

Periodic national surveys

National surveys of OHRQoL in the United States have been limited largely to single-item questions on perceived oral health status or treatment needs, while a few other countries, such as Australia and the United Kingdom , have included in their national, cross-sectional surveys a larger number of impacts, such as pain, problems with chewing or talking, feeling self-conscious or embarrassed, and becoming less cheerful or irritable because of oral health problems. The OHRQoL measure most frequently used in the United States is to ask the individual to rate his or her oral health on a scale from “excellent” to “poor.” These ratings require that individuals engage in an evaluation of their oral health status that effectively aggregates across whatever dimensions of health are important to them. Research suggests that adults’ ratings of their own oral health and parents’ ratings of their children’s oral health are influenced by a combination of factors, such as presence or absence of disease, physical functioning, psychologic discomfort, health behaviors, and self-ratings of general health .

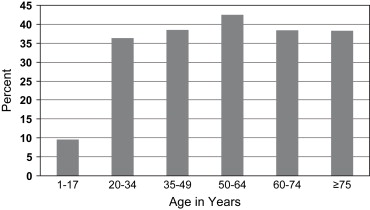

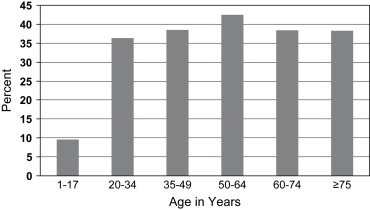

The percentage of adults or parents of children in the United States reporting the condition of their own teeth and mouth or that of their children to be “poor or fair” is displayed by age in Fig. 1 . According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, about 10% of parents rated their children’s oral health as fair or poor . The percentage of adults reporting their own oral health as fair or poor was dramatically larger than for children, but varied only slightly by age group from 36.3% to 42.5% . Some differences in the estimates between children and adults can be attributed to surrogate reporting by the parent for the child and differences in how the questions were asked, but for adults in particular, oral conditions have a large impact on well being.

Major disparities in perceived oral health status also are apparent from national surveys in the United States ( Table 2 ). The most disadvantaged groups, as measured by education or poverty status, are almost twice as likely to report fair or poor oral health as the most advantaged groups . For example, 62% of adults who did not graduate from high school report fair or poor oral health status, compared with 28% who had some education beyond high school. When combined with societal measures of impact, such as days lost from school or work, oral conditions have substantial importance .

| Age | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 20–64 years | 65 years and older |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 33.9% | 34.6% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 50.2% | 61.2% |

| Mexican American | 57.7% | 66.9% |

| Poverty status | ||

| Less than 100% FPL | 59.9% | 67.8% |

| 100%–199% FPL | 57.7% | 49.0% |

| Greater than 200% FPL | 30.3% | 30.3% |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 62.3% | 55.5% |

| High school | 47.8% | 36.3% |

| More than high school | 28.2% | 30.3% |

| Overall | 38.8% | 38.3% |

Single-item, impact specific questions, such as the impact of dental problems on chewing, can be helpful in determining the major dimensions through which dental problems affect well being. The 2003 National Children’s Dental Health Survey in the United Kingdom asked parents to consider whether their children had experienced any problems in the previous 12 months as a result of the condition of their teeth and gums . Most parents did not think that their children had been affected by an oral condition. However, from 22% to 34% of parents of 5- to 15-year-old children, depending on age, reported some type of problem occasionally or more often during the 12 months preceding the interview. The most common problem was pain (16% to 26%), followed by being embarrassed, self-conscious or worried (4% to 10%), problems with chewing or talking (5% to 7%), having to stop playing a musical instrument (4% to 7%), and becoming less cheerful or more irritable (4% to 6%). Impacts on social functioning or general health affected 2% or less of children.

On the other hand, most adults (73%) in Britain report that oral health does affect their QoL, with most of the impact being positive . Negative impacts were more likely to be reported for the physical domain (eg, 9% reported a bad effect for eating) than for the social (eg, 3% for social life) or psychologic (eg, 3% mood) domains. More than 17% of Australians reported avoiding some foods because of problems with their teeth, mouth or dentures in a 2004 to 2006 national survey of adults .

At least 17 dental multi-item questionnaires have been developed to measure the negative impacts of disease and ill health in adults . A small number of multi-item instruments that have been developed only recently to measure OHRQoL among children can be added to the list of adult instruments . These multi-item questionnaires are helpful in studying determinants or risks for OHRQoL, particularly when OHRQoL impacts are summarized as a scale, and the findings can be valuable to those planning community-based intervention programs. These scales, with their varying domains, provide methodologic advantages in the analysis of determinants of OHRQoL because they show more variation and responsiveness than do single-item questions. Furthermore, they can more explicitly and accurately measure the domains that are considered important in conceptual models of QoL. A major disadvantage of these instruments is their large number of questions, in some cases more than 70, which limits their use to epidemiologic or clinical studies where OHRQoL outcomes are a major focus.

Nevertheless, a number of large, cross-sectional epidemiologic studies have been done in the United States and other countries that have allowed exploration of correlations or predictors of OHRQoL through sophisticated analytic techniques. These studies, conducted mostly in older adults, are helpful in examining determinants of OHRQoL and how impacts vary by important social characteristics of populations. Slade has reviewed findings from these types of studies and concluded that the factors associated with poorer OHRQoL are “fewer teeth, more diseased teeth, other untreated dental disease, unmet treatment needs, episodic dental visits to treat dental problems and lower socioeconomic status.” He also concludes that “nonwhite respondents (in the United States) generally have poorer OHRQoL compared with white respondents.”

Another important question for dental public health practice is whether some oral diseases or conditions present particularly strong and negative impacts on well being, and therefore should receive special consideration in planning dental public health programs. It appears that dentofacial problems, such as cleft lip or palate, skeletal and dental mal-alignments, oral and pharyngeal cancers, temporo-mandibular joint dysfunctions, salivary gland dysfunctions resulting from conditions such as Sjogren’s syndrome, and severe early childhood caries can result in particularly strong impacts on QoL .

Public health surveillance

The National Oral Health Surveillance System (NOHSS), designed to provide more frequent and more local data on the burden of oral diseases in the United States than the national periodic surveys discussed in the previous section, does not include any OHRQoL measures. Rather, it includes eight indicators for oral disease (oral and pharyngeal cancer, dental caries experience, untreated dental caries, complete tooth loss), use of the oral health care delivery system (dental visits, teeth cleaning, dental sealants), and the status of community water fluoridation . The NOHSS relies primarily on available national surveys that can provide state-level estimates, as well as clinical information collected by state or local programs according to a standard protocol. The national survey, known as the Behavioral Risk Factor and Surveillance System (BFRSS), which provides several indicators (visits, cleaning, tooth loss), does not include any patient- or population-reported outcomes for oral health status.

Very few states have their own surveillance system for the impact of oral diseases and conditions on well being. Colorado and North Carolina have implemented annual surveys that include OHRQoL indicators for children, specifically, a single question on global oral health status . In those states, parents of school-aged children or younger who are sampled as part of the BRFSS, which only includes information about adults, are included in a follow-up survey about their children’s health. The reported OHRQoL measure on these state surveys is a single question on global oral health status . The results are similar to the national average, with 9.1% and 7.8% of parents in Colorado and North Carolina, respectively, reporting that their children’s oral health is fair or poor. Major disparities in parents’ perceived condition of children’s teeth also are apparent, with, for example, 20.7% of Hispanic parents in North Carolina reporting fair or poor oral health status for their children, compared with 6.5% of other ethnic groups. The growing racial and ethnic diversity of the United States population also is, of course, an important consideration in planning dental public health programs. Such planning should entail consideration not only of cultural differences in perceptions of treatment needs, but also how these diverse groups interpret and perceive their OHRQoL.

Lastly, public health research in recent years has been enriched by concepts and ideas from the life course framework that emphasize the role of events that occur early in life on population health outcomes later in life. This approach should be extended to include effects on OHRQoL. For example, a recent study from Brazil reported that the incidence of enamel defects is associated with life course events, such as early malnutrition and pre- and postnatal infections among a cohort of children from low-income families . Although the investigators did not measure changes in quality of life, their results point to the importance of considering OHRQoL as an outcome measure in longitudinal population-based studies.

Application of OHRQoL in public health practice

The importance of oral health in people’s quality of life is a well ingrained, but to date a largely implied perspective, in the philosophy, goals, and strategies for dental public health practice (see Table 1 ). The three core functions of public health practice necessary for population health, articulated by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the future of public health and the associated 14 essential dental public health services related to these that were provided by the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) , are designed to identify and monitor oral health problems in populations and ensure that effective polices and programs are in place to help alleviate these problems. OHRQoL is at the core of the framework and definition for public health practice provided by the IOM and ASTDD documents.

Yet, attention to this aspect of oral health status remains largely at the conceptual level, with less attention having been given to its application to dental public health activities, such as the measurement of OHRQoL in state and local surveillance and population-based surveys, population screening programs to identify those needing referral and treatment, or the evaluation of how the implementation of public health programs affects OHRQoL, a point to be discussed in this article. At present, no data collection mechanism or process is in place in the United States to comprehensively monitor the national burden of oral diseases from the perspective of OHRQoL. This deficit is particularly important because one of the two Healthy People 2010 goals for the nation is to improve quality of life . The next two sections review use of OHRQoL measures in periodic national surveys and ongoing surveillance of oral health.

Periodic national surveys

National surveys of OHRQoL in the United States have been limited largely to single-item questions on perceived oral health status or treatment needs, while a few other countries, such as Australia and the United Kingdom , have included in their national, cross-sectional surveys a larger number of impacts, such as pain, problems with chewing or talking, feeling self-conscious or embarrassed, and becoming less cheerful or irritable because of oral health problems. The OHRQoL measure most frequently used in the United States is to ask the individual to rate his or her oral health on a scale from “excellent” to “poor.” These ratings require that individuals engage in an evaluation of their oral health status that effectively aggregates across whatever dimensions of health are important to them. Research suggests that adults’ ratings of their own oral health and parents’ ratings of their children’s oral health are influenced by a combination of factors, such as presence or absence of disease, physical functioning, psychologic discomfort, health behaviors, and self-ratings of general health .

The percentage of adults or parents of children in the United States reporting the condition of their own teeth and mouth or that of their children to be “poor or fair” is displayed by age in Fig. 1 . According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, about 10% of parents rated their children’s oral health as fair or poor . The percentage of adults reporting their own oral health as fair or poor was dramatically larger than for children, but varied only slightly by age group from 36.3% to 42.5% . Some differences in the estimates between children and adults can be attributed to surrogate reporting by the parent for the child and differences in how the questions were asked, but for adults in particular, oral conditions have a large impact on well being.