History of the Procedure

The first mention of exenteration can be found in a German textbook of ophthalmology written by Bartisch in 1583. The same surgical approach was proposed for certain cases of exophthalmos. Langenbeck in 1821 and Dupuytren in 1833 were the earliest to undertake this surgical technique. Collins in 1864 and von Arlt in 1874 gave detailed accounts of the surgical method of orbital exenteration as it is performed today. The operation was reserved for malignant tumors of the orbit and the periorbital tissues, and the exenteration socket was left to spontaneously epithelialize by granulation tissue. In 1872, Streatfeild introduced the conservative orbital exenteration with the lid-sparing technique, in which the eyelids were sutured together, thus hiding the empty orbital cavity. In 1909, Golovine proposed the extended orbital exenteration, which included adjacent structures such as the maxillary sinuses.

History of the Procedure

The first mention of exenteration can be found in a German textbook of ophthalmology written by Bartisch in 1583. The same surgical approach was proposed for certain cases of exophthalmos. Langenbeck in 1821 and Dupuytren in 1833 were the earliest to undertake this surgical technique. Collins in 1864 and von Arlt in 1874 gave detailed accounts of the surgical method of orbital exenteration as it is performed today. The operation was reserved for malignant tumors of the orbit and the periorbital tissues, and the exenteration socket was left to spontaneously epithelialize by granulation tissue. In 1872, Streatfeild introduced the conservative orbital exenteration with the lid-sparing technique, in which the eyelids were sutured together, thus hiding the empty orbital cavity. In 1909, Golovine proposed the extended orbital exenteration, which included adjacent structures such as the maxillary sinuses.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Orbital tumors can be classified into three main groups, according to their origin: (1) primary lesions, which originate from the orbit itself; (2) secondary lesions, which extend into the orbit from neighboring structures (intracranial tumors, nasal cavity tumors, tumors of the paranasal sinuses or skin); and (3) metastatic tumors.

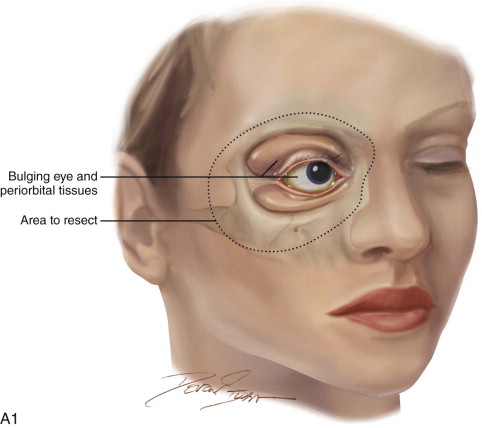

Approximately 10% of all orbital malignancies are extensions of tumors originating from the nose and paranasal sinuses ( Figure 102-1 ). The most common of these malignancies is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the maxillary sinus, the nasal cavity and the ethmoids. Other malignant epithelial sinonasal tumors include lacrimal and other minor salivary gland tumors. Extension of the tumor usually takes place in an infiltrating fashion, creating a space-occupying mass in the orbit. The surrounding inflammatory reaction leads to proptosis, diplopia, visual acuity and field loss, and edema of the eyelids and conjunctiva. Chemosis and epiphora may develop as late symptoms. Proptosis from sinonasal tumor infiltration into the orbit is usually nonaxial and is associated with pain and paresthesia. Pain combined with complete ptosis and ophthalmoplegia (superior orbital fissure syndrome, or Rochon-Duvigneaud syndrome ), or these findings plus visual loss (orbital apex syndrome), indicate that the disease process has extended into the orbital apex and cavernous sinus ( Figure 102-2 ).

There are four grades of orbital involvement through the paranasal sinuses: (1) tumor adjacent to the orbit, without infiltration of the orbital wall; (2) tumor eroding the orbital wall without ocular bulb displacement; (3) tumor eroding and infiltrating the orbital wall, displacing the orbital content, without periorbital involvement; and (4) tumor invading the orbit with periorbital invasion. In cases of obvious intraperiosteal or bony orbital tumor involvement, the orbit with the adjacent bone and sinuses should be removed. The conventional treatment of sinonasal malignancies with orbital extension is maxillectomy with orbital exenteration. Ethmoidal malignancies invade the orbit through the thin lamina papyracea in more than 80% of cases.

Limitations and Contraindications

The term orbital exenteration refers to removal of the entire orbital contents, including part or all of the eyelids, eyelashes, globe, optic nerve, extraocular muscles, lacrimal gland, and lacrimal drainage system, in addition to the orbital fibroconnective and adipose tissues. Orbital exenterations are classified as subtotal, total, and extended. Extended exenteration entails the resection of the orbital walls and/or resection of the adjacent paranasal sinuses. Lesser orbital resections, such as globe enucleation, are not discussed here.

Contraindications to orbital exenteration include medical unsuitability for major surgery and anesthesia and unwillingness of the patient to consent to the operation.

Technique: Total Orbital Exenteration

Step 1:

Patient Positioning

The patient is placed in a reverse Trendelenburg position, and the head is supported in a slightly extended position with a Mayfield headrest or by use of a shoulder roll. The eyelids are sutured together with two silk sutures. The line of the desired incision is marked with a marking pen, and an epinephrine-containing local anesthetic is injected. A circumferential incision is made through the skin overlying the orbital rim, passing just inside the orbital margin. Medially, the incision lies on the anterior lacrimal crest; laterally, it passes close to the outer canthus. On the nasal wall of the orbit, the periosteum must be raised gently because the orbital plate of the ethmoid is often very fragile, and a sinus tract can result if the ethmoid air cells are opened ( Figure 102-3, A and B ).

Step 2:

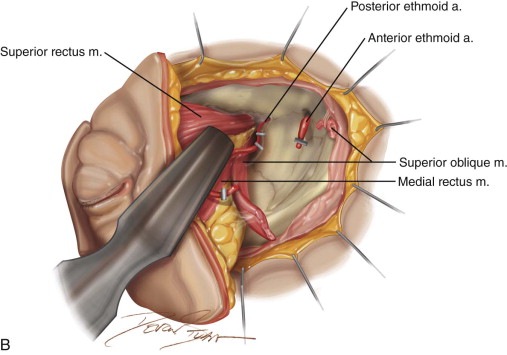

Circumferential Elevation of the Periorbita

The incision is continued with unipolar cautery with a fine needle tip (Colorado tip). To minimize bleeding, the dissection can begin superiorly, around 12 o’clock, and proceed laterally, postponing dissection of the vascular nasal quadrant to the end of the procedure. The periorbita is best incised a few millimeters outside the orbit. The periorbita is then elevated with a Molt #9 or similar periosteal elevator with the aid of malleable retractors. At the anterior lacrimal crest, the lacrimal sac is reflected laterally with the orbital contents as the periosteum is separated from the nasal wall. The nasolacrimal duct is identified and transected as the dissection proceeds from the nasal wall to the floor of the orbit. During this dissection, bleeding is managed by suction or packing with neurosurgical cottonoids soaked in oxymetazoline. Laterally the temporal and malar branches of the lacrimal artery enter the zygoma, and medially the anterior ethmoidal artery passes from the orbit into the anterior ethmoidal foramen. These vessels are exposed as they pass between periosteum and bone and are clipped or coagulated to avoid troublesome bleeding in the depths of the wound. When the circumferential soft tissue dissection is complete, access for hemostasis is enhanced (see Figure 102-3, B ).

Step 3:

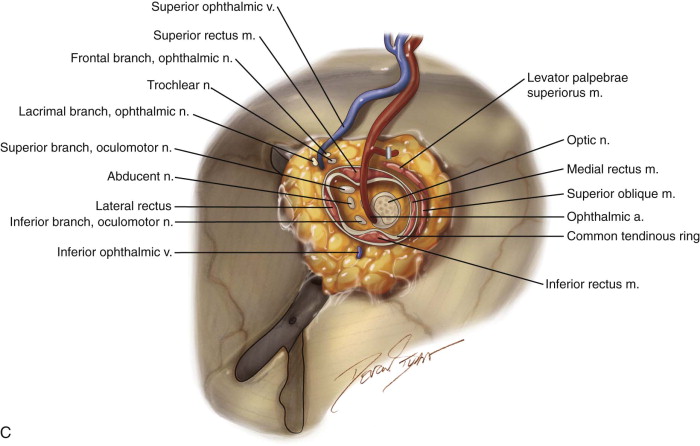

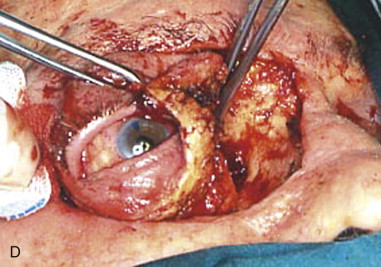

Transection of Orbital Apex Tissue Bundle

At the orbital apex, the apical bundle of soft tissues, including the extraocular muscles, blood vessels, and nerves, is circumferentially dissected. Before transection, the anesthesiologist should be informed because an oculocardiac reflex will ensue, with significant bradycardia or transient asystole. The apical tissue bundle at the tip of the orbital cone cannot be clamped or cut with one move. The bundle is approached from its nasal aspect, a Dietrich or other right-angle hemostat is placed, and the pedicle is cut above the hemostat with unipolar cautery or a curved pair of scissors (e.g., Fomon scissors). The maneuver is repeated laterally and inferiorly to free the apex from orbital soft tissues. The bleeding sources of the apex (ophthalmic artery and vein) should be identified, clamped, and tied. Excessive electrocautery at the apex can damage the stump of the optic nerve, and this damage may extend into the optic chiasm. During orbital exenteration, most of the bleeding originates from the supraorbital and infraorbital bundles, the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, and the ophthalmic artery at the apex. Although the apical bleeding is the most significant, all sites of bleeding are easier to access and control after removal of the orbital contents. After removal of the orbital contents, it may be possible to apply smaller clamps proximal to those previously used and to reduce the size of the apical tissue stump by removal of more tissue ( Figure 102-3, C and D ).

Step 4:

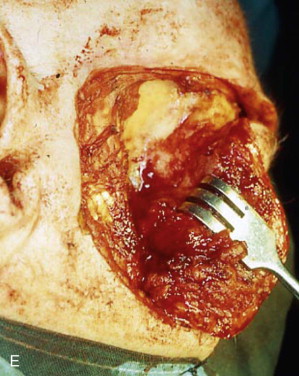

Resection of Orbital Walls as Needed

The orbital walls are examined for any evidence of neoplastic involvement. In most areas of the orbit, it is preferable to deeply incise the bone with an oscillating saw along the predetermined limits of resection and then attempt to remove the bone en bloc with a strong rongeur. In other sites, a sharp osteotome and a mallet may be needed to remove pathologic bone in layers ( Figure 102-3, E ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses