History of the Procedure

The treatment of nasal fractures has been known since antiquity. Descriptions of nasal injuries and fractures can be found in the papyrus (circa 1600 BC) owned by Edwin Smith. In those cases, besides the usual magical incantations, a logical approach was recommended. Repositioning of nasal fractures was achieved by inserting tampons of linen saturated with grease and honey into the nostrils. This internal packing was externally reinforced by two stiff, splintlike rolls of linen, probably one on each side of the nose, which was then bandaged.

The early documented reports on the management of nasal fractures date back to Hippocrates. He defined a simple classification for nasal injuries, and he proposed simple treatment modalities for each type of injury. Surprisingly, these simple techniques formed the basis for the modern techniques that have evolved.

History of the Procedure

The treatment of nasal fractures has been known since antiquity. Descriptions of nasal injuries and fractures can be found in the papyrus (circa 1600 BC) owned by Edwin Smith. In those cases, besides the usual magical incantations, a logical approach was recommended. Repositioning of nasal fractures was achieved by inserting tampons of linen saturated with grease and honey into the nostrils. This internal packing was externally reinforced by two stiff, splintlike rolls of linen, probably one on each side of the nose, which was then bandaged.

The early documented reports on the management of nasal fractures date back to Hippocrates. He defined a simple classification for nasal injuries, and he proposed simple treatment modalities for each type of injury. Surprisingly, these simple techniques formed the basis for the modern techniques that have evolved.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Esthetic deformities and functional changes are two main indications for treatment of nasal fractures. A careful clinical examination, thorough interview, and sometimes precise analysis of preinjury photographs of the patient can help the surgeon discover any change of shape or any breathing pattern deformity that may have developed after nasal trauma. In some cases, nasal fractures without displacement or functional deformities may be best left untreated.

Limitations and Contraindications

- 1.

Excessive swelling and edema: Swelling may disturb clinical judgment and may lead to inadequate or improper reduction. The fractured nose should be treated before any considerable swelling develops (up to a few hours after trauma); otherwise, the procedure should be postponed until the swelling has subsided (5 to 8 days after injury). Corticosteroid prescriptions and thermotherapy (cold compress for the first day and warm compress for the next 2 days) may be beneficial in shortening this period of delay.

- 2.

Panfacial fractures: Nasal fractures frequently occur with fractures of other facial bones. The treatment of multiple facial fractures follows a general rule: the fractures are reduced bottom up and from the outside in; the broken nose is the last to be addressed. Nasotracheal intubation may be a problem for nasal fracture repair. In such cases, after rigid fixation of all facial fractures, the nasotracheal tube is changed to oral intubation, and the nasal fracture then is treated as an isolated nasal fracture. The surgeon should never underestimate the importance of a nasal fracture even when focusing on other, seemingly more complex fractures; this mistake may never be compensated for subsequently, even with several revision operations.

- 3.

Naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) fracture: In NOE fractures, the nasal fracture is part of a more complex injury that requires special considerations. Inaccurate diagnosis may lead to undertreatment and several postoperative complications.

- 4.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage: CSF leakage is a possibility in severe nasal injuries. This leakage usually is controlled through conservative modalities, such as head position and diet. Some patients with resistant leakage that lasts several days may require open surgery.

It is imperative that all these procedure be done under the direct supervision of a neurosurgeon. All nasal procedures should be done after neurosurgical clearance of the patient.

Technique: Closed Reduction of Nasal Fractures

Early Management

The proper technique to fix an acute nasal fracture greatly depends on the amount of displacement or depression of the nasal bones and the degree of septal involvement. Treatment varies, ranging from simple observation and prescription of antiinflammatory drugs, to manual manipulation and reduction, to forceps reduction, to more complex open septorhinoplasty techniques.

Step 1:

Anesthesia

A nasal fracture may be reduced using local or general anesthesia. Local anesthesia may seem painful in an awake patient, and injection of even a few milliliters of a local anesthetic may distort the nose; it also may interfere with intraoperative judgments, the simplicity of the fracture, and the patient’s cooperation. The surgeon’s and the patient’s desires are the main factors in the selection of the type of anesthesia. Local anesthesia usually involves anesthetic nasal packs (e.g., 4% cocaine packs) and injection of local anesthetics via infiltration and nerve blocks, usually using 1% lidocaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine as the drug of choice; 5 cc of this solution is dispersed around the nose and lateral sidewalls. A few drops of the local anesthetic is enough to block the infraorbital nerves on each side; the septum, internal mucosa, and subciliary block need another 3 cc. It is important to bear in mind that in all cases, there is the possibility of an unacceptable reduction and the need for a much more complex procedure; therefore, the surgeon and the patient should be ready for a possible change from local to general anesthesia if a much more complex technique in that session. Alternatively, a second session may be scheduled for later to treat the patient under general anesthesia.

Step 2:

Hand Manipulation

For hand manipulation, the direction of finger pressure is opposite the vector of injury and the direction of nasal displacement. Both hands hold the patient’s head, and the thumbs are used to mobilize and reduce the nasal bones. The clinical appearance of the nose is checked precisely in case the reduction is not passive or an obvious deformity exists; in such cases, other steps may be required ( Figure 72-1, A ).

Step 3:

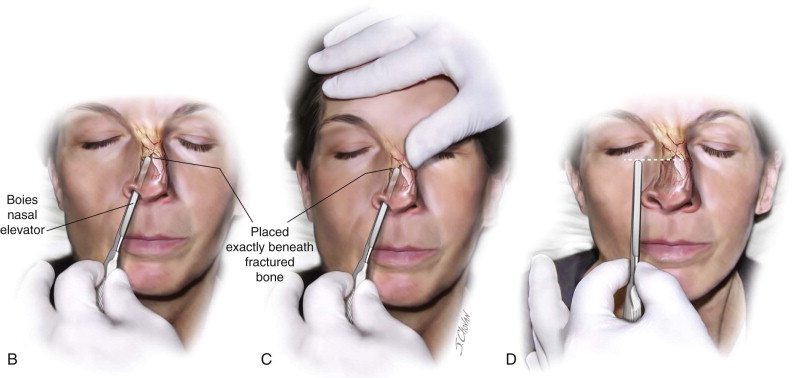

Nasal Bone Elevation

The fractured nose is held by the nondominant hand. A Boer elevator or any blunt instrument (e.g., a surgical knife handle) is inserted into the nose and gently passed inside the nostril. The fractured area is approached gradually, and the fractured bone is elevated. In some cases, the other (nondominant) hand may be used simultaneously to manually mold the nose. Finger palpation and visual observation are used to check the adequacy of reduction. The blunt instrument should be exactly beneath the fractured bone; this blind technique may be made more precise by adjusting the length of the instrument out of the nose ( Figure 72-1, B to D ).

Step 4:

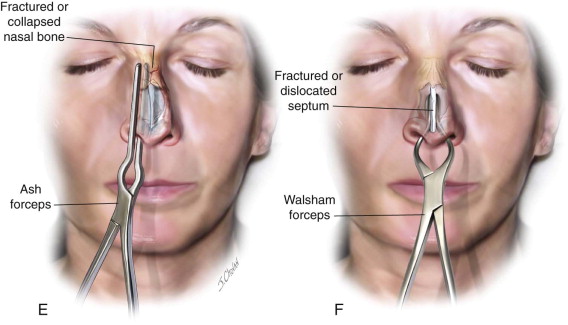

Forceps Reduction

Nasal forceps are specifically designed to grasp the displaced nasal tissue and move it in the desired direction. In nasal bone fractures, Ash forceps are opened, and one of the straight beaks of the forceps is inserted into the nose and gently moved forward until it is under the fracture site. The beaks then are gently closed, and the fracture site is held between one beak, which is inside the nose, and the other beak, which is placed over the skin. The fracture is reduced by gentle manipulation of the forceps handle.

In the case of a fractured or dislocated septum, the beaks of a Walsham forceps are passed into the nostrils, and the nasal septum is held by closing the beaks. The septum then is moved and reduced to its proper place. Walsham forceps may also be used to elevate a crushed and collapsed nose. In these cases, a hard stent is inserted into both nostrils and fixed by sutures to prevent collapse of the reduced structures ( Figure 72-1, E and F ).

Step 5:

Internal Splints and Packs

After reduction of the nose, an internal splint or pack is used to hold the reduced parts in place and prevent hematomas or synechiae. Hard nasal splints (e.g., Doyle splints) have small tubes for breathing, so they are much more comfortable for patients. In a crushed nasal fracture, they may offer better control of fractured segments and may be left in the nose for a longer time postoperatively. Some surgeons prefer nasal packs impregnated with antibiotics; however, these packs are less tolerable and must be removed within a shorter period.

Step 6:

Nasal Taping and External Splints

Small, narrow tape strips are used to redrape the skin on the nasal framework and to prevent edema formation. The tape also protects the skin from contact with hard external splints. A hard thermoplastic nasal splint is softened in warm water, trimmed and reshaped for the nose, and then placed over the taped nose. Light finger pressure is applied until the splint has cooled and is hardened by the application of cold water. External splints may remain for 5 to 7 days postoperatively ( Figure 72-1, G ).

Alternative Techniques

Most nasal fractures are easily treated with the conservative techniques described, although some recent studies show many unfavorable results and complex sequelae in large series. It is logical to proceed with more advanced procedures in the early phases of treatment if any difficulty is encountered or inadequate reduction is assumed. These alternative techniques are usually undertaken to prevent postoperative functional and esthetic dissatisfaction.

Alternative Technique 1: Conventional Intubation: Submental Intubation

In multiple bone fractures of the face or panfacial trauma, the nasotracheal tube usually is changed to an orotracheal tube to enable work on a broken nose; however, sometimes concerns about edema and difficult reintubation may make the operating team consider other options.

The use of submental intubation has been frequently reported for simultaneous work on the jaws and nasal bones. In this technique, the surgeon injects a local anesthetic and makes an incision in the submental area. After creating an intraoral communication, the endotracheal tube is passed and orotracheal intubation is performed.

Alternative Technique 2: Bone Reduction: Internal Approach Incisions and Access

For the internal approach, which is used for direct access to fractured bones, an intercartilaginous incision is made on the fracture side; then, using scissors for dissection, direct access to the fracture zone is obtained. Next, a Boer elevator is introduced through the dissected area, and broken bone is directly elevated and reduced. Some hold that this leads to a more precise reduction and repair in depressed nasal bones; however, the outcome depends on the surgeon’s experience and the severity of the fracture.

Alternative Technique 3: Bone Reduction: Use of an Osteotome

In some cases, the fractured bone segments are not passively reduced and may have resulting steps or palpable irregularities. An osteotomy with gentle manipulation may turn a greenstick fracture or locked bone fragments into a complete bone fracture; in this manner, passive reduction may be achieved.

In other scenarios, a nasal fracture may mimic an incomplete osteotomy in rhinoplasty. An external perforated osteotomy may easily help reduce this type of deformity. In this technique, a small stab incision is made in the skin on the lateral side of the nose. Then, with a 2-mm osteotomy and a few mallet strokes, the surgeon creates an accurate fracture in a well-designed line. The bone fragment is mobilized completely and reduced. The osteotomy site is gently palpated for bone spicules or irregularities, which are corrected if present.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses