Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

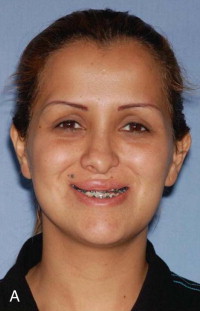

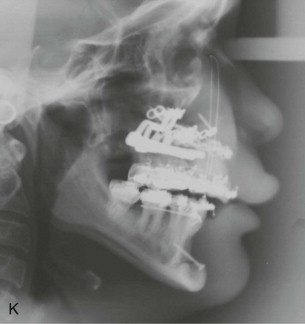

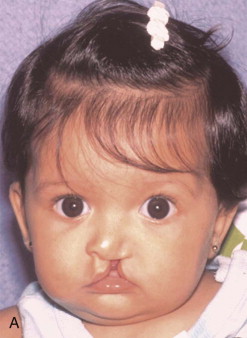

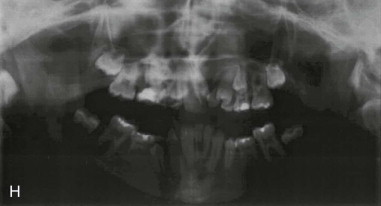

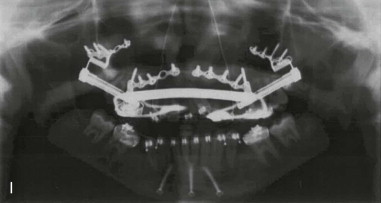

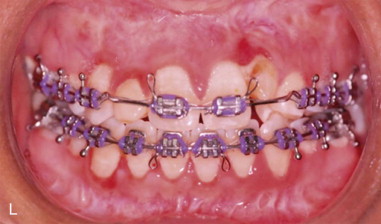

Three-dimensional (3D) maxillary deficiency may be present in a variety of craniofacial syndromes, clefts, and some idiopathic clinical situations. The deficiency may be present at different maxillary levels and must be treated accordingly. These levels may include Le Fort I level, either low or high (see Figures 40-1 and 40-2 ); quadrangular Le Fort I level. This chapter covers only intraoral devices; it does not address the problem of total midface or frontofacial deficiency.

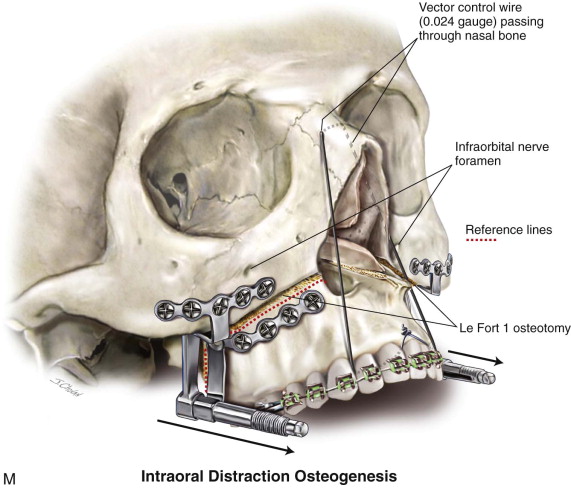

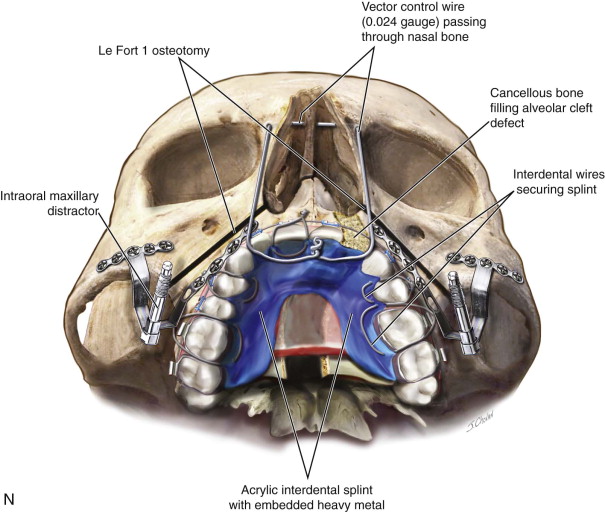

Traditional surgery has some limitations in terms of the amount of movement, the need for iliac crest bone grafts, and the stability and quality of bone. The soft tissues also can be a limitation, especially clefts and scar tissue from multiple surgeries. Intraoral distraction osteogenesis may be a better choice as an alternative method; it provides better stability and easier surgery (based on performing the osteotomies and fixing the appliances); no bone grafts are needed, and costs are reduced because the patient is discharged from the hospital earlier and is able to resume activities in a week’s time. Through the years, two different approaches have been published for distraction osteogenesis in the craniofacial region: extraoral distractors or intraoral distractors. Extraoral distractors involve a semicircular metal structure fixed to the skull with multiple screws with a vertical bar connected to facial plates by wires and coils to exert the anteroposterior pressure and advance the midface. There have been modifications and improvements to ensure skull stability and vector control, and attachments and connectors are available from various companies. The common problems are social inconvenience, facial scars and, more important, all patients have the distractors removed before completing the distraction consolidation phase (in large movements this would require up to a year); consequently, the stability is jeopardized.

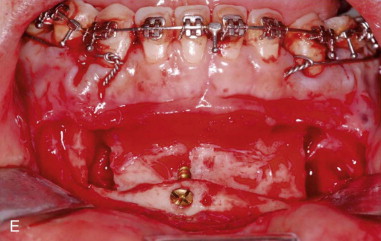

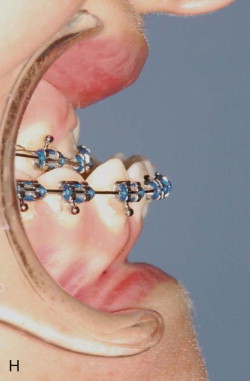

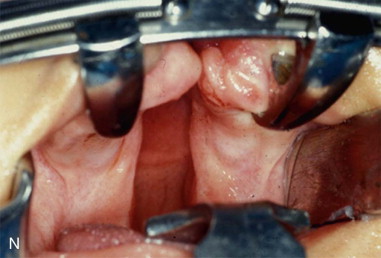

Internal maxillary distractors are based on a solid body with a barrel to be activated between anterior and posterior plates for bony fixation. Different designs had been published to improve bone anchorage, easier activation, and vector control and to facilitate removal. An understanding of biology and biomechanics is fundamental to predictably correct facial anomalies. The distraction protocol is based on the amount of movement, the age of the patient, and the quality and quantity of bone; minor or standard deformities are corrected with traditional surgery.

To obtain optimal results, ideally orthodontics will be used in the correction of facial and occlusal discrepancies. The surgery must be planned in 3D models to perform the model surgery; the distractors are prebent, preshaped, and activated to full movement; and the vector is planned to the objective movement. Once the appliances have been activated and perfect occlusion has been obtained in the model, the actual surgery is performed with proper vectors; the size of the distractors (e.g., 15, 20, 25 mm) and the length of the screws are measured and will be ready for surgery. All this work is done before the surgical intervention and must be supervised by the group expert and discussed with the orthodontist. The surgeon ensures that the final positioning of the midface is occlusally stable and must be maintained until bone rigidity occurs, after the distraction’s consolidation phase. This may take 3 to 12 months, depending on the variables of amount of movement, age of the patient, and quantity and quality of bone. The distractor appliances are easy for the patient to use and can remain in place comfortably for a long time, with the patient resuming regular activities a few days after surgery.

Some patients show divergences from the treatment plan, even though the appliances were prepared to obtain the best occlusion possible. In such cases the surgeon needs to install a secondary method to make postoperative changes in the vector, such as circumferential vertical anterior suspension wires, or he or she must change the position of the anterior plate by changing the screws under intravenous sedation. Under no circumstances should the surgeon remove the distraction appliances and expect guiding elastics to improve or maintain the occlusion. The collagen fibers in the distraction chamber are under tension, awaiting mineralization in the consolidation stage; if the appliance’s rigidity collapses or it is removed, the fibers contract, the segments become unstable, and complete recurrence results.

Chin, Guerrero, Salyer, Wangerin, and Kessler were pioneers in developing internal devices or in using existing mandibular technology to advance the maxilla at different levels, following the true indications for distraction osteogenesis.

History of the Procedure

Three-dimensional (3D) maxillary deficiency may be present in a variety of craniofacial syndromes, clefts, and some idiopathic clinical situations. The deficiency may be present at different maxillary levels and must be treated accordingly. These levels may include Le Fort I level, either low or high (see Figures 40-1

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses