Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

In 1923, Crile described the marginal mandibulectomy as an incision that is “carried down to the bone and thence into the bone by a sharp chisel or saw, so that a slice of bone can be split off in one piece, bearing the undisturbed cancer off as on a bone platter.” Even today, surgery remains the primary treatment for malignant disease of the mandible and its surrounding soft tissues due to the risk of osteoradionecrosis and oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma’s relative radio-insensitivity. In the mid-twentieth century, a segmental resection was the only treatment option for larger gingival and floor of mouth (FOM) lesions, or any bony lesions, as it was thought that malignant spread could occur through the periosteal lymphatics of the mandible. In the 1970s, Marchetta refuted this theory and showed that metastasis occurred through local lymphatics and not through the periosteum. This discovery allowed for the possibility of marginal (rim or sagittal) mandibulectomy over a segmental resection. The marginal resections have had excellent early oncologic success and have remained a sound surgical treatment for perimandibular carcinomas. In 1993, Barttlebort published a benchmark paper that showed a significant decrease in mandibular strength when the remaining basilar bone height was shortened below 10 mm. He also compared rim resection to sagittal resection. Rim resection showed both greater strength and better oncologic treatment of affected bone. Controversy still exists as to how carcinoma invades the bone. Brown reported that bony invasion is via direct infiltration of the bone, not preferentially to a certain location of bone or through the inferior alveolar canal. This allows the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) to be spared if not clinically or radiographically involved.

This was a significant change for patients, especially in the prereconstruction plate and vascular graft era, who had to suffer significant cosmetic and functional deficits with segmental resections. As technology and imaging has improved, there are now more accurate ways to determine the extent of lesions in and around the mandible, giving us both better reconstructive options as well as diagnostic planning tools to aid in surgical planning for resection. Use of marginal mandibulectomy over segmental resection does remain somewhat controversial, but a number of studies have shown its efficacy as a treatment for oral carcinoma with minimal invasion into the cortical bone.

History of the Procedure

In 1923, Crile described the marginal mandibulectomy as an incision that is “carried down to the bone and thence into the bone by a sharp chisel or saw, so that a slice of bone can be split off in one piece, bearing the undisturbed cancer off as on a bone platter.” Even today, surgery remains the primary treatment for malignant disease of the mandible and its surrounding soft tissues due to the risk of osteoradionecrosis and oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma’s relative radio-insensitivity. In the mid-twentieth century, a segmental resection was the only treatment option for larger gingival and floor of mouth (FOM) lesions, or any bony lesions, as it was thought that malignant spread could occur through the periosteal lymphatics of the mandible. In the 1970s, Marchetta refuted this theory and showed that metastasis occurred through local lymphatics and not through the periosteum. This discovery allowed for the possibility of marginal (rim or sagittal) mandibulectomy over a segmental resection. The marginal resections have had excellent early oncologic success and have remained a sound surgical treatment for perimandibular carcinomas. In 1993, Barttlebort published a benchmark paper that showed a significant decrease in mandibular strength when the remaining basilar bone height was shortened below 10 mm. He also compared rim resection to sagittal resection. Rim resection showed both greater strength and better oncologic treatment of affected bone. Controversy still exists as to how carcinoma invades the bone. Brown reported that bony invasion is via direct infiltration of the bone, not preferentially to a certain location of bone or through the inferior alveolar canal. This allows the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) to be spared if not clinically or radiographically involved.

This was a significant change for patients, especially in the prereconstruction plate and vascular graft era, who had to suffer significant cosmetic and functional deficits with segmental resections. As technology and imaging has improved, there are now more accurate ways to determine the extent of lesions in and around the mandible, giving us both better reconstructive options as well as diagnostic planning tools to aid in surgical planning for resection. Use of marginal mandibulectomy over segmental resection does remain somewhat controversial, but a number of studies have shown its efficacy as a treatment for oral carcinoma with minimal invasion into the cortical bone.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Marginal mandibulectomy is a useful surgical procedure for treating a number of malignant and benign processes. It is useful for malignant lesions that affect the soft tissues of the alveolus, buccal sulcus, or FOM that abut the mandibular periosteum but do not invade into the marrow space of the mandible. Marginal resection is also indicated when advanced imaging or an intraoperative examination of bone using periosteal stripping shows changes in cortical bone. Tei and colleagues determined that if there is radiographic erosion, not a “moth-eaten” defect, of the mandible above the inferior alveolar canal secondary to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the alveolus or gingiva, the inferior border of the mandible can be preserved. If the defect is a “moth-eaten” defect that is confined to the alveolus, only marginal resection is again acceptable. Marginal mandibulectomy is also an excellent alternative to segmental resection for nononcologic processes such as osteonecrosis, osteomyelitis, or benign tumors that leave at least 10 mm of basilar bone.

Limitations and Contraindications

There are a number of circumstances that preclude marginal mandibulectomy. Patients who have previously undergone radiation therapy are poor candidates for marginal resection. Irradiated bone is more susceptible to osteoradionecrosis, and there is an increased likelihood of bony invasion of the disease process and fracture of the residual mandible. Primary bone carcinomas or gross invasion of the medullary space require segmental resection, not marginal resection. Edentulous patients with an affected atrophic mandible should not have a marginal mandibulectomy because there could be insufficient remaining basilar bone to withstand the forces of mastication and potentially lead to pathologic fracture. Preoperative imaging such as a panoramic radiograph is helpful for assessing the superior-inferior height of the mandible along with oncologic imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans according to preference ( Figure 83-1 ). Where there is extensive bone invasion or a thin atrophic mandible, a segmental resection is the resection of choice.

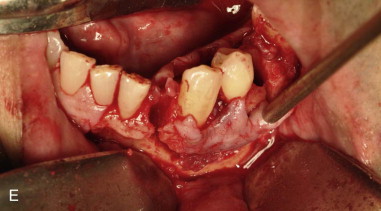

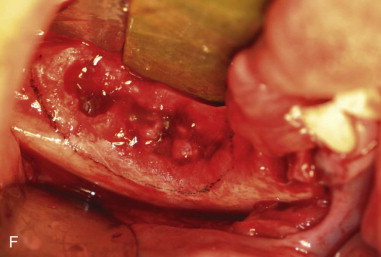

Technique: Marginal Mandibulectomy

Step 1:

Intubation

Nasoendotracheal intubation with the tube secured to the forehead using tape and sutured to the membranous septum and columella, or a tracheostomy secured with appropriate taping or sutures is the preferred airway, depending on the extent of soft tissue resection planned with the procedure. For smaller lateral sulcus lesions that do not include the floor of mouth, oral RAE intubation could be considered. If using a CO 2 laser, the surgeon must consider the use of an armored endotracheal tube depending on the location of the lesion and the type of intubation ( Figure 83-2, A and B ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses