Fractures of the frontal sinus/sinuses make up about 5-15% of all facial fractures in the adult patient. This is a relatively low frequency of occurrence. However, there are a myriad of short- and long-term potential complications associated with this type of injury that may involve not only the frontal sinuses, but more importantly the brain. Because of its potential for high morbidity and mortality, clinicians managing this type of injury must be able to address the acute injury appropriately and be cognizant of the potential complications and their inherent management.

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the surgical anatomy, radiographic and clinical evaluation of patients, classification of injuries, management of fractures, and complications associated with frontal sinus fractures.

SURGICAL ANATOMY

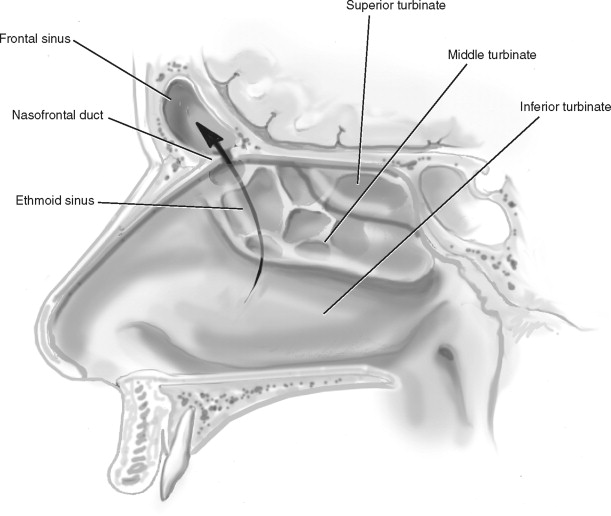

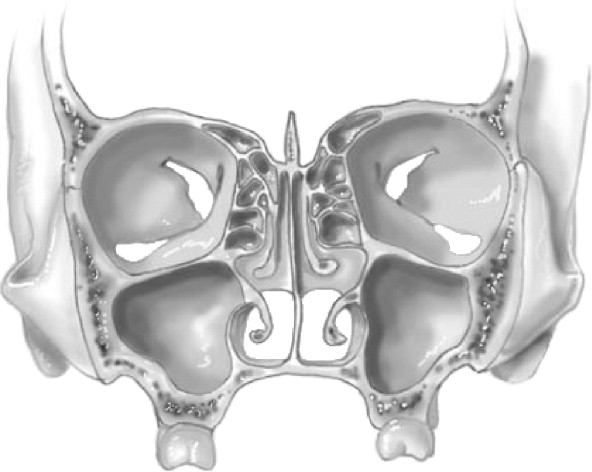

The frontal sinus or sinuses are single or usually paired paranasal sinuses embedded within the frontal bar of the frontal bone ( Figures 15-1 to 15-3 ). They are outpouchings of the ethmoidal air cells with a typical size of 3.5 × 2.5 × 1.5 cm, although significant variations can occur. There usually exists a bony septum separating the right and left sinus. Initial pneumatization of the frontal sinus begins in the early stages of the second trimester, and radiographic evidence of the sinus can be seen by the age of 6 years. The floor of the sinus forms a portion of the orbital roof; therefore, any medial orbital roof fractures may involve the frontal sinus. The posterior wall separates the anterior cranial fossa from the sinus. This wall is rather thin and can be fractured and displaced into the brain as a result of blunt trauma. Arterial blood supply to the sinus is via the supraorbital artery and the anterior ethmoidal arteries. The venous system mirrors that of the arterial system plus the diploic veins of the frontal bone known as the veins of Breschet and the superior sagittal sinuses. Physiology of the frontal sinus is similar to other paranasal sinuses of the face. Pseudostratified ciliated columnar respiratory epithelium lines the sinus. Mucin is cleared by the ciliary flow (rate of 250 cycles/min) and is drained from the sinus through the naso-frontal ducts (NFDs) located at the medial aspect of the floor into the middle meatus of the nose. This location of NFD is of clinical significance since trauma to the floor of the sinus or medial aspect of the sinus/orbital wall can injure the NFD.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

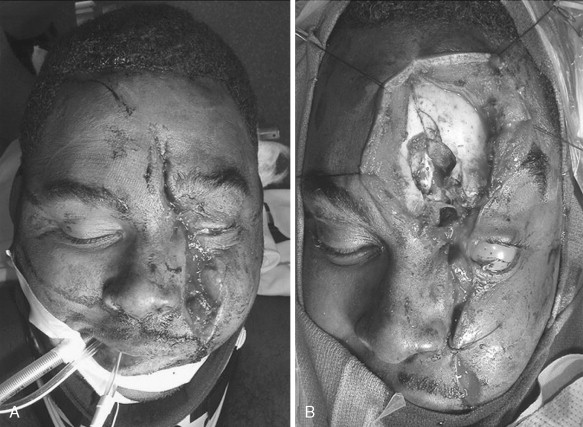

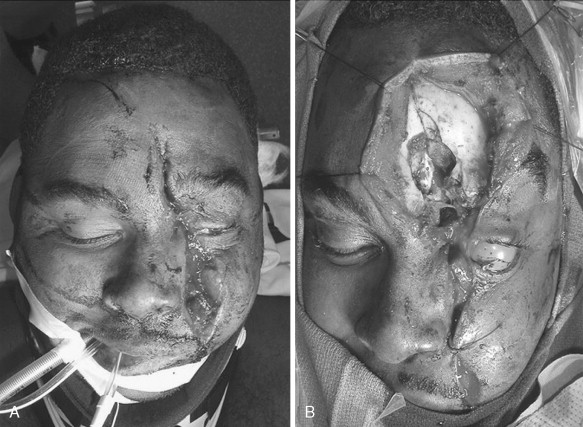

Patients with isolated frontal sinus fractures usually have periorbital ecchymosis and pain in the forehead region. This finding in the presence of blunt trauma to the forehead along with lacerations in the region should raise the suspicion of frontal sinus fracture ( Figures 15-4 and 15-5 ). Blunt or penetrating trauma to this region can also produce altered sensation of the forehead and scalp resulting from injury to the supraorbital and supratrochlear neurovascular bundles. If the patient is seen shortly after the injury, one might also appreciate a depression in the bony forehead. This finding is seldom seen because of the soft tissue swelling. Crepitation might be palpable in evaluating such bony injuries. The examiner should always be cognizant of other concomitant injuries such as intracranial bleeding and cervical injuries ( Figures 15-6 and 15-7 ).

Evaluation of the nose for possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is imperative in patients with frontal sinus fractures. If the posterior table of the sinus or the base of the skull in the region of the cribriform plate is fractured, the dura might be lacerated, causing leakage of CSF into the sinus and then into the middle meatus. Confirmation of the CSF from the nose can be done at bedside by performing the double halo test or ring test. A small sample of the nasal drainage is placed on a cotton sheet; if a red central ring (blood) surrounded by a clear halo (CSF) is observed, the practitioner should suspect leakage of CSF. Other confirmatory tests include sending samples of the fluid to the laboratory for evaluation of chloride and glucose and the β2-transferrin test. CSF will usually have high chloride and low glucose concentration compared with serum. Presence of β2-transferrin, a protein marker found exclusively in CSF and aqueous humor, from the nasal drainage can be done via electrophoresis. It is important to remember that patients with frontal sinus trauma may also have associated orbital and naso-ethmoidal injuries. These injuries and their managements are discussed elsewhere in this book.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Patients with isolated frontal sinus fractures usually have periorbital ecchymosis and pain in the forehead region. This finding in the presence of blunt trauma to the forehead along with lacerations in the region should raise the suspicion of frontal sinus fracture ( Figures 15-4 and 15-5 ). Blunt or penetrating trauma to this region can also produce altered sensation of the forehead and scalp resulting from injury to the supraorbital and supratrochlear neurovascular bundles. If the patient is seen shortly after the injury, one might also appreciate a depression in the bony forehead. This finding is seldom seen because of the soft tissue swelling. Crepitation might be palpable in evaluating such bony injuries. The examiner should always be cognizant of other concomitant injuries such as intracranial bleeding and cervical injuries ( Figures 15-6 and 15-7 ).

Evaluation of the nose for possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is imperative in patients with frontal sinus fractures. If the posterior table of the sinus or the base of the skull in the region of the cribriform plate is fractured, the dura might be lacerated, causing leakage of CSF into the sinus and then into the middle meatus. Confirmation of the CSF from the nose can be done at bedside by performing the double halo test or ring test. A small sample of the nasal drainage is placed on a cotton sheet; if a red central ring (blood) surrounded by a clear halo (CSF) is observed, the practitioner should suspect leakage of CSF. Other confirmatory tests include sending samples of the fluid to the laboratory for evaluation of chloride and glucose and the β2-transferrin test. CSF will usually have high chloride and low glucose concentration compared with serum. Presence of β2-transferrin, a protein marker found exclusively in CSF and aqueous humor, from the nasal drainage can be done via electrophoresis. It is important to remember that patients with frontal sinus trauma may also have associated orbital and naso-ethmoidal injuries. These injuries and their managements are discussed elsewhere in this book.

RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION

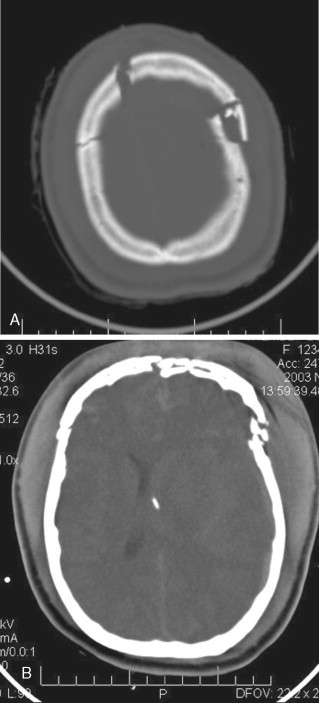

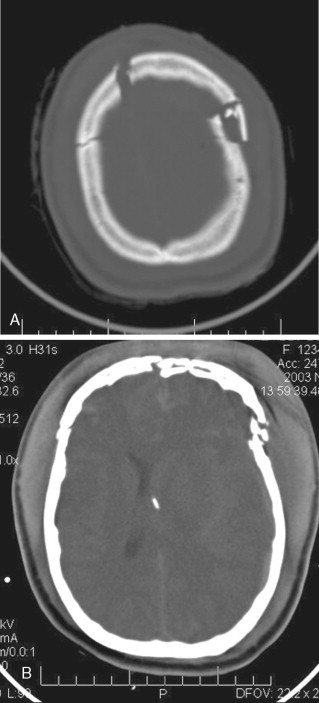

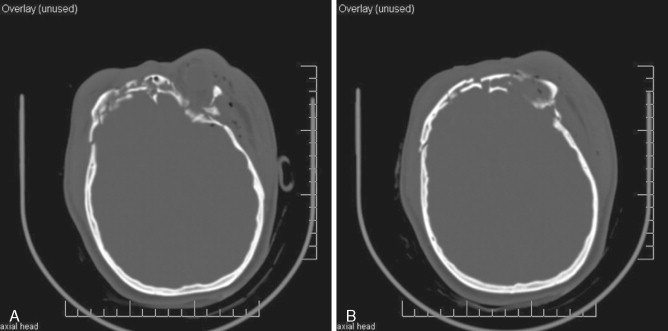

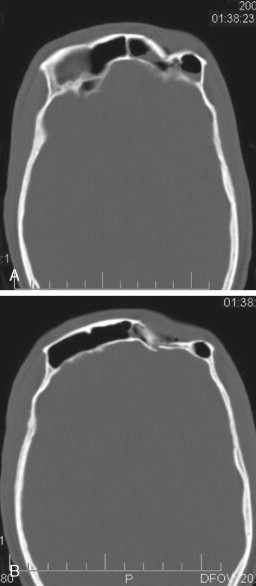

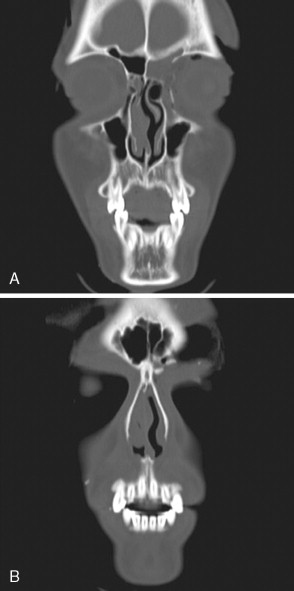

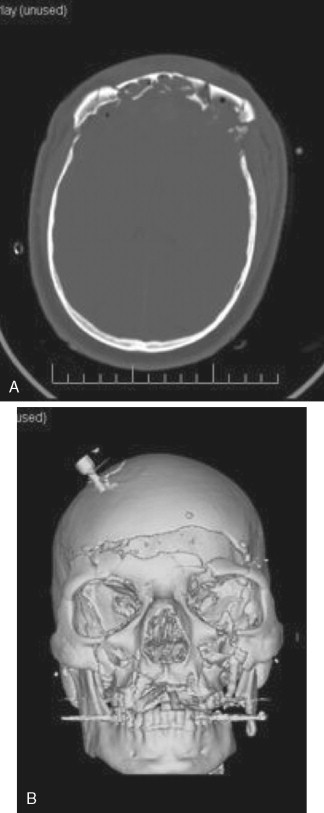

The gold standard method of evaluation for frontal sinus fractures is computed tomography (CT). This is also true of most mid and upper face trauma. Although multiple planes can be obtained, the two most useful planes of view are axial and coronal on a CT scan ( Figures 15-8 to 15-10 ). The ideal thickness of such a scan should be 1.0 mm. Generally no contrast is needed for evaluation of facial fractures, although intracranial bleeding usually requires addition of intravenous contrast to a CT scan. Axial views can give a clear view of the anterior table and posterior table as well as evidence of intracranial impingement. Coronal views can give clues to the status of the naso-frontal ducts, floor of the sinus, and involvement of other adjacent structures such as the orbital roofs. In cases of significant comminution, 3D images can also be quite helpful ( Figure 15-11 ).

CLASSIFICATION OF FRONTAL SINUS FRACTURES

There have been numerous attempts to classify, universally, fractures of the frontal sinus. These have added nothing other than confusion to the literature for the most part. The simplest and most basic classification of frontal sinus fractures is one that clearly describes three specific areas: the anterior table, the posterior table, and the status of the naso-frontal ducts. An isolated anterior table fracture can be classified on the basis of its displacement. If the fracture involves a displacement greater than the width of the anterior table, it is considered a displaced fracture and consideration should be given to surgical repair in order to prevent a cosmetic deformity ( Figure 15-12

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses