Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The development of the branchial anomalies, presenting as cysts, branchial sinuses, or branchial fistulas, is widely accepted to be the result of incomplete involution of the branchial apparatus. In 1832, Ascherson first used the term branchial cyst . In 1864, Housinger introduced the term branchial fistula . Since then, many terms have been widely used in literature and practice. Many treatment modalities have been applied to branchial anomalies including incision and drainage and sclerotherapy; however, complete surgical excision has proved to be the definitive treatment. Historically, the cysts were only excised after becoming symptomatic, but recurrence rates as high as 20% were reported. Current literature supports prophylactic excision in that these lesions are a significant source of morbidity from secondary infection, which can increase the difficulty of excision and the possibility of incomplete resection from postinflammatory fibrosis or scar. To fully excise the tract of the sinus or fistula, an incision along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle was once applied but later substituted by the classical and more cosmetic “stepladder” incision first described by Bailey in 1933. Later, stripping techniques (or a combined approach) were successfully introduced for complete excision of the branchial sinus and fistula. More recently, endoscopic and microscopic approaches have been applied.

Etiology

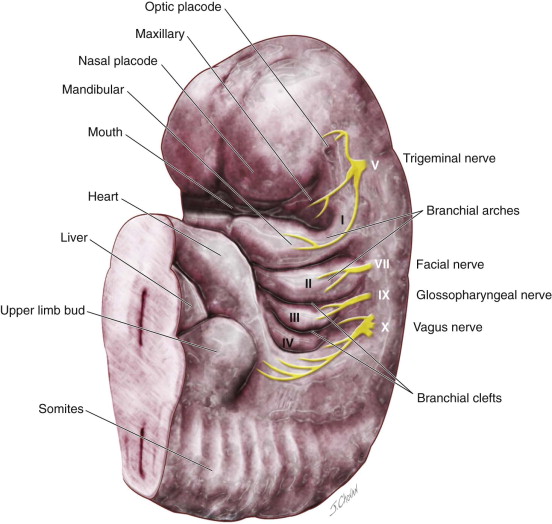

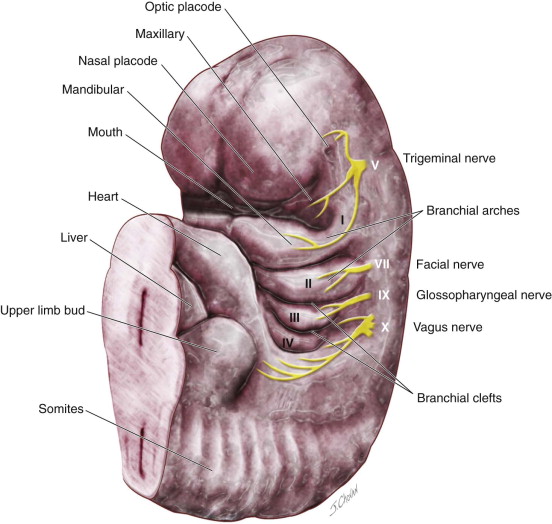

Several theories have been proposed for the development of branchial anomalies, including branchial apparatus theory, cervical sinus theory, thymopharyngeal theory, and squamous epithelium inclusion theory. The branchial apparatus theory is the most commonly accepted. Branchial anomalies are a consequence of abnormal development of the branchial apparatus during embryogenesis. Persistence of branchial apparatus remnants—due to incomplete closure or incomplete obliteration of the fetal branchial arches, pouches, or both—results in anomalies such as cysts, sinuses, fistulas, or an island of cartilage ( Figure 92-1 ).

Presentation

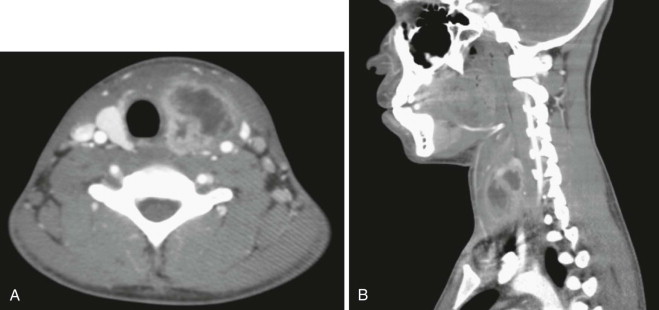

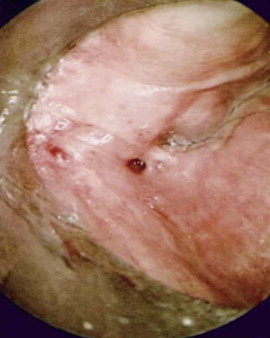

Branchial anomalies are divided into first cleft, second cleft, and third and fourth pouch anomaly. Among these categories, second cleft anomalies account for 95% and first cleft anomalies account for 1% to 4%. Third and fourth pouch anomalies, most of which are sinuses and similarly presented around the piriform sinus, are rare and are studied as case reports in the literature. Most cases are diagnosed in the first and second decades but may present well into adulthood. Clinically, a branchial anomaly may present as a cyst, sinus, or fistula. A cyst is lined by epithelium but has no external opening. A sinus is a blind pocket that opens internally (persistence of a pouch) or externally (persistence of a cleft). A fistula is a tract that has both internal and external openings. Branchial fistulas and sinuses seem to be diseases of childhood, whereas branchial cysts occur mainly in adulthood. It is generally believed that the distribution of these diseases has no statistically significant difference in sex or side except that the fourth branchial pouch anomalies are predominantly left-sided (95% to 97%). The branchial cleft cyst typically is a unilateral, painless, slow-growing, fluctuant, and smooth mass, sometimes with episodes of inflammation. It usually appears and enlarges after an upper respiratory infection. If infected, it can present as a firm, painful, immobile mass with or without systemic symptoms and signs of infection. The cyst may become abscessed, which can lead to rupture and cause a permanent sinus or recurrent cyst. It is reported that approximately 20% of lesions have been infected at least once by the time of surgery ( Figure 92-2 ). Interim infection causes acute morbidity and increases the difficulty of complete excision. In the case of a branchial cleft sinus or fistula, about 80% of sinuses open to the skin and fewer open to the pharynx. The presence of skin anomalies or swelling can be seen, sometimes with mucous or purulent discharge from the tract.

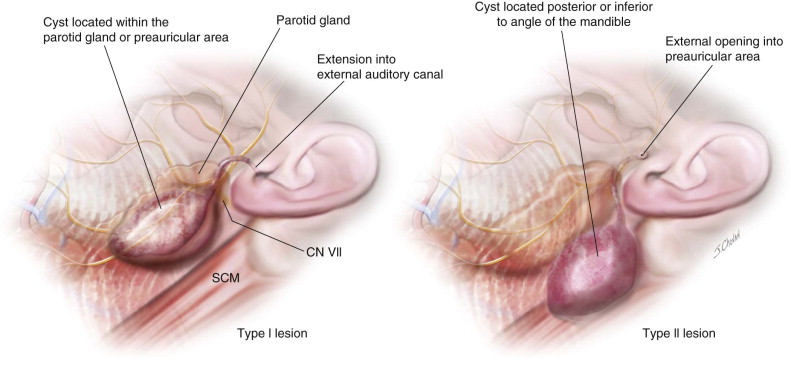

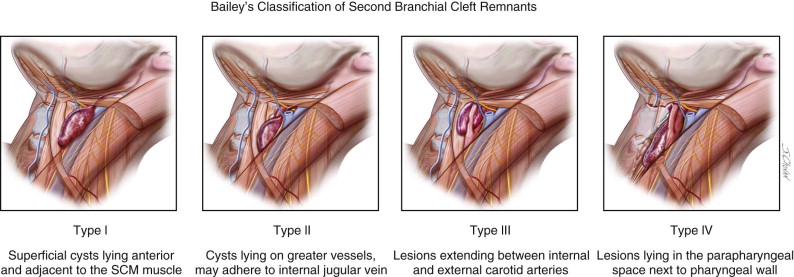

The location of branchial anomalies, usually parallel to a line from the tragus to the sternoclavicular joint, differs according to their origin. First branchial remnants are relatively rare and are classified as type I or type II lesions. Type I lesions present in the parotid or preauricular region as cysts or sinuses, whereas type II lesions present more posterior or inferior to the angle of the mandible. Either may extend into the external auditory canal ( Figure 92-3 ). The external opening is usually in the preauricular region or cervical region above the hyoid bone. Second branchial cleft remnants are located anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, mostly in the junction between the upper one third and lower two thirds, and have been classified by Bailey as type I (superficial cysts lying anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and adjacent to it), type II (cysts lying on the great vessels and may be adherent to the internal jugular vein), type III (lesions extending between the internal and external carotid arteries), and type IV (lesions lying in the parapharyngeal space next to the pharyngeal wall) ( Figure 92-4 ).

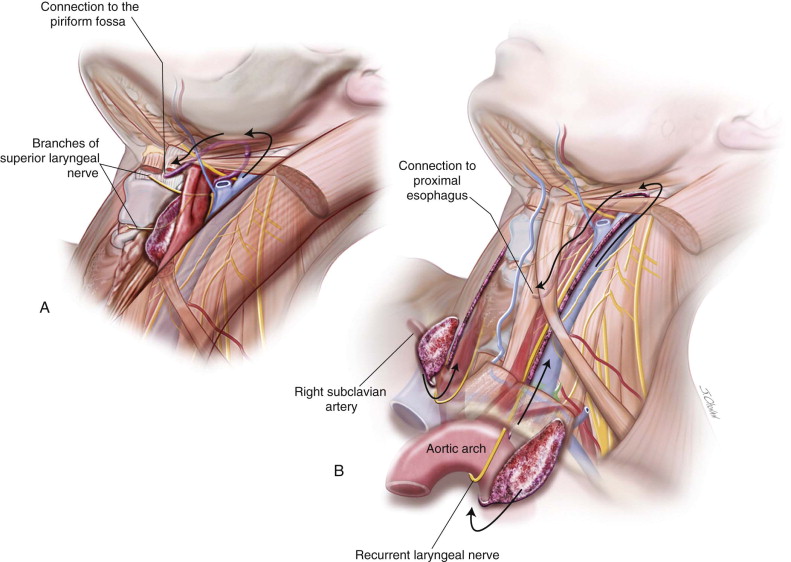

If the cyst is large enough, it may cause mass effect and asymmetry of the neck as well as dyspnea, dysphagia, and dysphonia. Third and fourth cleft anomalies ( Figure 92-5 ) with noncommunicating or noninfected communicating cysts may initially present as cold thyroid nodules. When infected, there will be a recurrent upper respiratory tract infection, neck or thyroid pain and tenderness, as well as neck swelling. Other presentations include cellulitis, hoarseness, odynophagia, thyroiditis, abscess, and stridor. The third and fourth branchial pouch sinus connects to the piriform fossa ( Figure 92-6 ) or proximal esophagus (fourth), which can lead to tracheal compression and respiratory distress in infancy due to rapid enlargement as the infant swallows saliva, formula, or milk. An external opening to the skin is rarely present but can sometimes be found in the lower neck mostly secondary to recurrent infection and repeated surgery. The cephalic third pouch remnants, associated with thymic tissue, are described as passing superior to the superior laryngeal nerve and posterior to the common carotid artery, whereas the caudal fourth pouch remnants, associated with thyroid tissue, usually emerge caudal to the thyroid cartilage and cricothyroid muscle and pass between the superior and recurrent laryngeal nerves, looping under the aortic arch on the left side and subclavian artery on the right side.

Histopathology

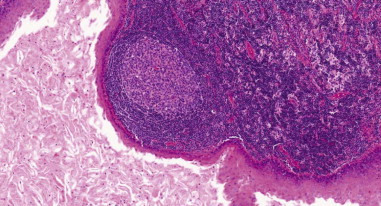

Histopathologically, there are differences between different anomalies. The first cleft anomalies have squamous epithelium (type I) or are mixed with skin adnexa or cartilage (type II). The second cleft anomalies are composed of a fibrocollagen wall surrounded by lymphoid tissue with follicle structures and a stratified squamous or columnar epithelium and occasionally respiratory epithelium ( Figure 92-7 ).

The sinus tracts of third and fourth cleft anomalies are lined by stratified squamous epithelium, which may be replaced in areas with respiratory epithelium. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to originate within branchial cleft lesions in adults, although it is extremely rare and controversial.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a branchial cleft cyst is primarily based on medical history, clinical presentations, and exclusion. Branchial anomalies should be suspected for any unexplained lateral neck masses or recurrent neck space infections. Diagnostic procedures include ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and fine-needle aspiration (FNA), as well as sinogram or barium contrast study for third and fourth cleft anomalies. Ultrasonography is a safe, inexpensive, and valuable exam that offers a reliable method to prove the cystic nature of the lesions. After the lesion has been proven cystic, a CT and MRI can be performed to define the exact dimensions and the relationship with the neighboring anatomic structures. As an established diagnostic procedure in the diagnosis of a neck mass, FNA may not be diagnostic but aids in confirming the cystic and benign nature of a neck swelling. Cyst aspiration may appear as a turbid, yellowish fluid that microscopically may exhibit squamous cells, polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, and cholesterol crystals. A barium esophagogram may reveal a sinus tract of third and fourth anomalies.

Differential Diagnosis

As cervical masses are common in clinical practice, branchial anomalies, although rare, should be included in the differential diagnosis. A differential diagnosis includes, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis-scrofula, thyroglossal duct cyst, cervical abscess, dermoid cyst, hyatid cyst cystic hygroma, paragangliomas, cystic metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma, and thyroid papillary carcinoma. Guldfred et al. reported a positive predictive value of 86% for the preoperative diagnosis of branchial cleft cyts and suggested considering every cystic lesion on the neck in the adult population as a potential cystic metastasis until proven otherwise.

Treatment

Because the branchial cleft lesions will not resolve spontaneously, an early complete surgical excision of an asymptomatic lesion could preclude or minimize the chance of infection and is considered the definitive treatment, whereas other treatment modalities, such as sclerosing agents, chemocauterization, radiation therapy, and incision and drainage, are considered noncurative or controversial.

History of the Procedure

The development of the branchial anomalies, presenting as cysts, branchial sinuses, or branchial fistulas, is widely accepted to be the result of incomplete involution of the branchial apparatus. In 1832, Ascherson first used the term branchial cyst . In 1864, Housinger introduced the term branchial fistula . Since then, many terms have been widely used in literature and practice. Many treatment modalities have been applied to branchial anomalies including incision and drainage and sclerotherapy; however, complete surgical excision has proved to be the definitive treatment. Historically, the cysts were only excised after becoming symptomatic, but recurrence rates as high as 20% were reported. Current literature supports prophylactic excision in that these lesions are a significant source of morbidity from secondary infection, which can increase the difficulty of excision and the possibility of incomplete resection from postinflammatory fibrosis or scar. To fully excise the tract of the sinus or fistula, an incision along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle was once applied but later substituted by the classical and more cosmetic “stepladder” incision first described by Bailey in 1933. Later, stripping techniques (or a combined approach) were successfully introduced for complete excision of the branchial sinus and fistula. More recently, endoscopic and microscopic approaches have been applied.

Etiology

Several theories have been proposed for the development of branchial anomalies, including branchial apparatus theory, cervical sinus theory, thymopharyngeal theory, and squamous epithelium inclusion theory. The branchial apparatus theory is the most commonly accepted. Branchial anomalies are a consequence of abnormal development of the branchial apparatus during embryogenesis. Persistence of branchial apparatus remnants—due to incomplete closure or incomplete obliteration of the fetal branchial arches, pouches, or both—results in anomalies such as cysts, sinuses, fistulas, or an island of cartilage ( Figure 92-1 ).

Presentation

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses