History of the Procedure

Only since the twentieth century has tracheostomy been considered a truly safe, predictable, and routine procedure. Surgical airways were once created only by a brave few who risked loss of their reputation. The procedure was frequently condemned, only to later be rediscovered. Although Egyptians likely performed the first tracheostomies around 3600 bc as pictured on ancient tablets, the first “medical” reference noting a healed tracheostomy scar was described in 2000 bc in the sacred book of Hindu medicine, Rig-Veda . The first known written description of tracheostomy technique came from Egypt around 1500 bc during the time of Imhotep. In 100 bc , Asclepiades further described the technique of the surgery, even though other experts of his time condemned the procedure. Whereas Hippocrates cited risks to the carotid arteries as the main reason to avoid a tracheostomy, Aretaeus of Cappadocia warned of infectious complications. Asclepiades’ enthusiasm for tracheostomy was later derided by Caelius Aurelianus as a “senseless, frivolous, and even criminal invention of Asclepiades.” Much of our historical understanding of tracheostomy comes from legends passed down through time. Alexander the Great reportedly used his sword to open the trachea of a soldier suffocating on a bone. The Babylonian Talmud describes placing a reed into the newborn trachea to assist in ventilation. Dante proclaimed tracheostomy “a suitable punishment for a sinner in the depths of the Inferno.”

Perhaps the most interesting detailed report came from Antyllus in 100 ad . His description of a horizontal incision between the tracheal rings mirrors the technique most commonly used today. Further historical accounts were sparse until the Renaissance. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, publications by Brasavola, Sanctorius, and Habicot reported on tracheostomies for airway obstruction due to infection and foreign bodies. In 1883, Trousseau reported on his lifesaving tracheostomies in 200 patients with diphtheria.

In 1921, Chevalier Jackson solidified modern tracheostomy indications and techniques, although he still advised against cricothyroidotomy. Tracheostomy is now performed routinely as an elective procedure.

History of the Procedure

Only since the twentieth century has tracheostomy been considered a truly safe, predictable, and routine procedure. Surgical airways were once created only by a brave few who risked loss of their reputation. The procedure was frequently condemned, only to later be rediscovered. Although Egyptians likely performed the first tracheostomies around 3600 bc as pictured on ancient tablets, the first “medical” reference noting a healed tracheostomy scar was described in 2000 bc in the sacred book of Hindu medicine, Rig-Veda . The first known written description of tracheostomy technique came from Egypt around 1500 bc during the time of Imhotep. In 100 bc , Asclepiades further described the technique of the surgery, even though other experts of his time condemned the procedure. Whereas Hippocrates cited risks to the carotid arteries as the main reason to avoid a tracheostomy, Aretaeus of Cappadocia warned of infectious complications. Asclepiades’ enthusiasm for tracheostomy was later derided by Caelius Aurelianus as a “senseless, frivolous, and even criminal invention of Asclepiades.” Much of our historical understanding of tracheostomy comes from legends passed down through time. Alexander the Great reportedly used his sword to open the trachea of a soldier suffocating on a bone. The Babylonian Talmud describes placing a reed into the newborn trachea to assist in ventilation. Dante proclaimed tracheostomy “a suitable punishment for a sinner in the depths of the Inferno.”

Perhaps the most interesting detailed report came from Antyllus in 100 ad . His description of a horizontal incision between the tracheal rings mirrors the technique most commonly used today. Further historical accounts were sparse until the Renaissance. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, publications by Brasavola, Sanctorius, and Habicot reported on tracheostomies for airway obstruction due to infection and foreign bodies. In 1883, Trousseau reported on his lifesaving tracheostomies in 200 patients with diphtheria.

In 1921, Chevalier Jackson solidified modern tracheostomy indications and techniques, although he still advised against cricothyroidotomy. Tracheostomy is now performed routinely as an elective procedure.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Indications for a tracheostomy and a cricothyroidotomy have been debated for centuries, and the indications are still debated but more rationalized. Most indications can be summarized as upper airway obstruction or impending upper airway obstruction. Tracheotomy refers to the procedure of creating an opening into the trachea, whereas tracheostomy refers to the actual opening resulting from the procedure. The two terms are often used interchangeably.

Prolonged intubation is a common indication for a tracheostomy. If a patient is expected to require mechanical ventilation for longer than 7 to 10 days, a tracheostomy is indicated. This improves patient comfort and has been shown to decrease the incidence of pneumonia as well as shorten hospital stays. Glottic injury due to prolonged intubation is also avoided with an early tracheostomy.

The inability to intubate is an indication for placement of a tracheostomy or cricothyroidotomy depending on the urgency of the situation and armamentarium available. When considering a cricothyroidotomy, other airway maneuvers in the difficult airway algorithm should also be considered. Similarly, patients with upper airway obstruction and stridor, air hunger, retractions, or bilateral vocal cord paralysis are indicated for surgical airway.

Head and neck trauma including facial fractures can also be an indication for a surgical airway. This may also include severe subcutaneous emphysema, airway edema, and facial fractures compromising the airway. Patients with these findings progressing toward loss of the airway should be considered for a surgical airway.

Tracheostomy is the gold standard for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and has a 100% cure rate. It bypasses the area of obstruction and can be used as a temporary or permanent (skin-lined tracheostomy) treatment depending on the severity of disease.

Tracheostomy is useful in extensive head and neck surgical procedures for control of the airway during surgery and in the immediate postoperative period. The surgeon should consider a tracheostomy when a major head and neck operation may cause significant upper airway edema or otherwise compromise the patient’s ability to maintain a safe airway.

Limitations and Contraindications

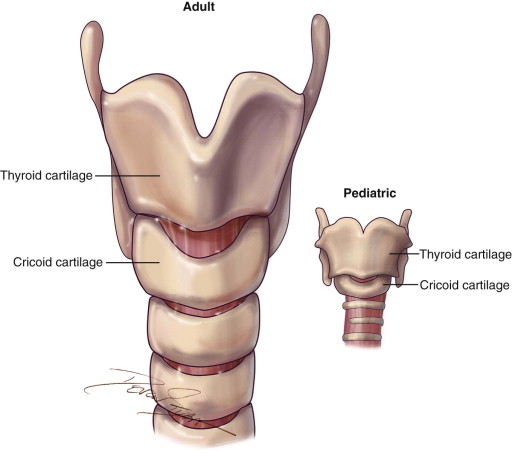

There are no true absolute contraindications, but there are instances when the surgical technique may need to be altered, such as presence of a high-riding innominate artery, goiter, or thyroid/laryngeal mass. In the pediatric population, a cricothyroidotomy is contraindicated because of the unfavorable anatomy and the high risk for tracheal stenosis postoperatively. Therefore, a formal tracheotomy should be performed on the pediatric population ( Figure 97-1 ).

Technique: Tracheostomy

Step 1:

Positioning

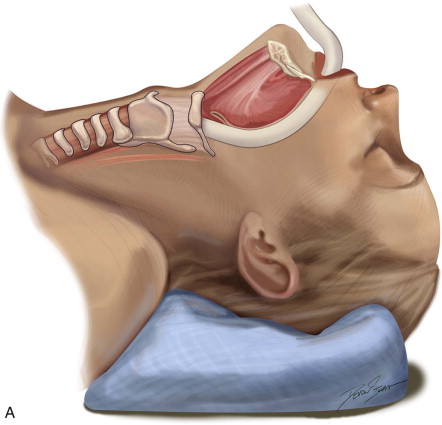

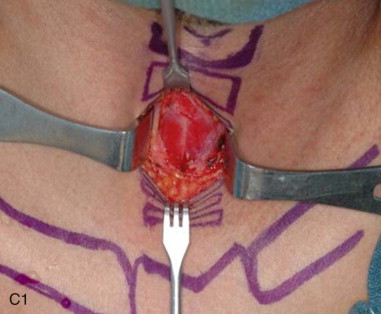

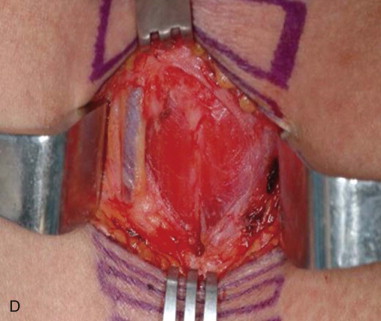

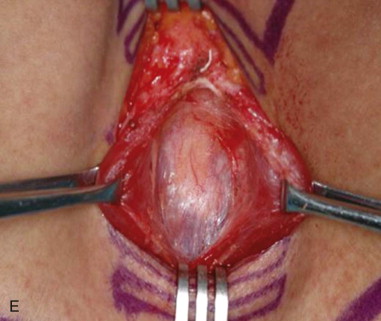

The patient is positioned on a shoulder roll with the neck in extension to maximize the distance between the cricoid cartilage and the sternal notch. Draping is performed to include the upper chest region in continuity with the neck. Landmarks are palpated and marked. The sternal notch and the cricoid cartilage are the most important landmarks, as the dissection will be performed between these two structures. A 4-cm horizontal incision line should be drawn halfway between the sternal notch and the cricoid cartilage. Alternatively, the surgeon may simply mark the incision 2 fingerbreadths above the sternal notch. If the surgeon is to remove the endotracheal tube, it should be prepped into the field with enough slack to be reconnected to the tracheostomy tube. If the anesthetist is to remove the tube, the tube should be positioned for access under the drapes. When a tracheostomy is performed as part of a larger head and neck procedure, the endotracheal tube is managed most simply by prepping it into the field along with the entire head and neck ( Figure 97-2, A and B ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses