Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The management of oral cancers of the mandible has been primarily surgical over the past 60 years. The decision between segmental and marginal resection is based on knowledge of the disease process and its pattern of invasion. In the 1950s, segmental resection was advocated based on the premise that the lingual periosteal lymphatics of the mandible were responsible for drainage of the tongue and floor of the mouth. In 1959, Panagopoulos proposed that bony invasion of the mandible occurred by direct extension of the tumor through nutrient canals. This proposal was based on his finding of tumor cells in Volkmann’s canals in a few of his cases. Involvement of the inferior alveolar canal was another consideration in the planning of resection of the mandible for oral cancer.

Possible routes of tumor entry into the mandible have been described by several authors. Byars suggested these pathways: through the upper surface of the mandible; through the mental foramen from primaries of the lip or oral cavity; and through the inferior border of the mandible for tumors extending from the neck. Others have suggested the periodontal membrane in the dentate patient or cortical defects in the edentulous mandible.

There are generally two patterns of invasion of the mandible. In the erosive pattern of spread, the tumor spreads on a broad front with a connective tissue layer, with osteoclasts between the tumor from the bone. In the invasive pattern of spread, islands of tumor advance independently, with little osteoclastic activity and no connective tissue layer separating the tumor from the bone.

Brown and Browne studied the pattern of invasion and the ways it can determine the type of mandibular resection. They looked at 33 patients who required segmental or rim/marginal resection and found that with more extensive intrusion into the mandible, the pattern was invasive. In areas where alveolar bone remained, the pattern was more likely to be erosive, and as the tumor extended into basal bone, its pattern changed to invasive. In areas where less alveolar bone is present, as in the posterior mandible, an invasive pattern is seen, unlike in the symphysis of the mandible. Brown and Browne proposed that in dentate patients, the site of entry is at the junction of the attached and reflected mucosa, which is usually 10 mm below the crest of the ridge. A surgeon considering a marginal resection should estimate from this area, rather than from the crest, for the planned resection to ensure clear margins.

History of the Procedure

The management of oral cancers of the mandible has been primarily surgical over the past 60 years. The decision between segmental and marginal resection is based on knowledge of the disease process and its pattern of invasion. In the 1950s, segmental resection was advocated based on the premise that the lingual periosteal lymphatics of the mandible were responsible for drainage of the tongue and floor of the mouth. In 1959, Panagopoulos proposed that bony invasion of the mandible occurred by direct extension of the tumor through nutrient canals. This proposal was based on his finding of tumor cells in Volkmann’s canals in a few of his cases. Involvement of the inferior alveolar canal was another consideration in the planning of resection of the mandible for oral cancer.

Possible routes of tumor entry into the mandible have been described by several authors. Byars suggested these pathways: through the upper surface of the mandible; through the mental foramen from primaries of the lip or oral cavity; and through the inferior border of the mandible for tumors extending from the neck. Others have suggested the periodontal membrane in the dentate patient or cortical defects in the edentulous mandible.

There are generally two patterns of invasion of the mandible. In the erosive pattern of spread, the tumor spreads on a broad front with a connective tissue layer, with osteoclasts between the tumor from the bone. In the invasive pattern of spread, islands of tumor advance independently, with little osteoclastic activity and no connective tissue layer separating the tumor from the bone.

Brown and Browne studied the pattern of invasion and the ways it can determine the type of mandibular resection. They looked at 33 patients who required segmental or rim/marginal resection and found that with more extensive intrusion into the mandible, the pattern was invasive. In areas where alveolar bone remained, the pattern was more likely to be erosive, and as the tumor extended into basal bone, its pattern changed to invasive. In areas where less alveolar bone is present, as in the posterior mandible, an invasive pattern is seen, unlike in the symphysis of the mandible. Brown and Browne proposed that in dentate patients, the site of entry is at the junction of the attached and reflected mucosa, which is usually 10 mm below the crest of the ridge. A surgeon considering a marginal resection should estimate from this area, rather than from the crest, for the planned resection to ensure clear margins.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

The term composite mandibulectomy can be defined as the excision of a portion of the mandible in continuity with the associated soft tissues involved by the pathologic process, plus or minus a neck dissection. Although soft tissue may be excised in continuity with the mandible for benign disease (e.g., ameloblastoma), this chapter discusses the management of malignant tumors. Cancers may arise primarily within the jaw (e.g., sarcoma, intraosseous carcinomas); however, most oral cancers are squamous cell tumors that arise in the soft tissue gingiva, retromolar, floor of the mouth, tongue, and buccal sites and secondarily involve bone. Due to limitations of space, this chapter reviews composite mandibular resection for oral tumors.

Marginal or rim resection of the mandible is defined as resection of the superior (alveolar) portion of the mandible, leaving the lower border in continuity. The decision to perform a marginal resection rather than a segmental resection is based primarily on the extent of bony invasion and the proximity of the tumor such that appropriate oncologic margins can be obtained. For small lesions (T1 or T2) lying close to the gingivolingual gutter on the lingual aspect of the mandible, the local control rates for rim/marginal resection were comparable to those for other procedures. Maintaining the inferior border of the mandible during cancer resection, where possible, is fundamental in oral cancer resection. By preserving the continuity of the mandible, the reconstructive plan is vastly simplified, and it spares the patient the morbidity associated with a free flap transfer. Bartellbort et al. recommended that when the rim/marginal mandibulectomy is performed, smooth, curved osteotomies without stepoffs were simple, biomechanically sound, and resulted in a low complication rate.

When bone is uninvolved clinically and radiologically by tumor and the periosteum can be stripped easily from intact cortical bone, there is no oncologic indication for bone removal. Bone still may be removed (e.g., gingival tumor) to ensure a 1-cm margin and complete excision. When the tumor is stuck to the periosteum and/or there is limited invasion of only cortical bone, a marginal resection may be performed. A panoral radiograph can be used to assess the vertical height of the mandible to ensure that at least 1 cm of bone can be maintained at the lower border.

Marginal mandibular resections, especially in the anterior region, may be approached intraorally. In a retrospective study of 46 patients, Ord et al. found that clinical examination, panoramic radiographs, and computed tomography (CT) scans were 82.6% accurate in diagnosing mandibular invasion. They found that the mandible was involved in 65% of patients who underwent segmental resection and 7.6% of those who had marginal resection. They concluded that marginal resection should be reserved for cases in which the cancer was in close proximity to the bone, exhibited minimal cortical invasion, or demonstrated an early erosive pattern.

If there is evidence of bony invasion through the cortex into medullary bone, a segmental resection is indicated. Most segmental resections require an in-continuity neck dissection and are approached through a cervical incision.

Using the Cawood and Howell classification of the edentulous mandible, Brown et al. suggested a guide for determination of an oncologically safe resection of the mandible if continuity of the mandible can be preserved. This was a retrospective case study based on 77 patients’ orthopantomograms (OPG), bone scintigraphy (BS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). They found the following suitability for marginal/rim resection: 58% among class I and class II (dentate or immediate extraction); 43% among class III and class IV (greater than 20-mm well-rounded or knife-edge ridge); and 6% among class V and class VI (less than 20-mm flat or depressed ridge form). In essence, the more resorbed mandible (i.e, class V and class VI) required a segmental resection.

If medullary bone invasion occurs in the body of the mandible, the entire nerve-bearing segment of bone is removed due to the potential for perineural spread by tumor along the inferior alveolar nerve. Posterior tumors (e.g., retromolar fossa) may require a lip split/mandibulotomy approach. Considerations in presurgical planning for mandibular resection include the type of incision to be used, the management of the neck, and the extent of the soft tissue and bone resection.

Technique: Composite Marginal Mandibular Resection

Step 1:

Preparation of Patient for Composite Marginal Mandibular Resection

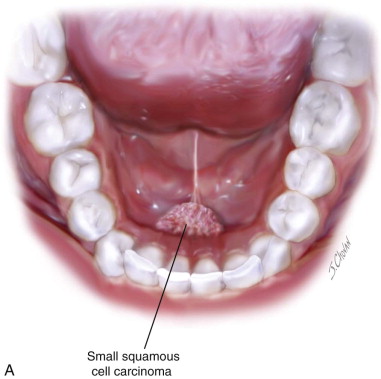

Composite marginal mandibular resection usually is undertaken for anterior floor of the mouth tumors involving the lingual periosteum/lingual cortical bone ( Figure 100-1, A ). The patient is positioned on either a Mayfield headrest or on a doughnut with a shoulder roll . General anesthesia with nasal intubation is used, although tracheotomy may be preferred. When neck dissection is indicated, it is usually performed as a discontinuity procedure. In the case of a larger T3 or T4 tumor, an in-continuity marginal resection with neck dissection can be performed using a pull-through approach (discussion of that procedure is beyond the scope of this chapter).

Step 2:

Planning Incision for the Composite Marginal Mandibular Resection

An intraoral approach is used. The oral mucosa is dried with suction and a laparotomy sponge. A 1-cm margin is marked with a marking pen around the palpable margin of the tumor. This margin usually includes the attached gingival tissue on the buccal aspect, even when the tumor is lingual in the floor of the mouth. The mucosa on the buccal aspect is incised with a needle tip electrocautery. Dissection is carried down to the mandibular bone through muscle, with the cut angled inferiorly toward the lower border. The periosteum at the depth of the cut is elevated with a periosteal elevator. A sulcular incision is made along the teeth distal to the proposed bone cuts on both sides. This is done to prevent tearing of the mucosa, a precaution that facilitates closure of the defect.

Step 3:

Soft Tissue Dissection

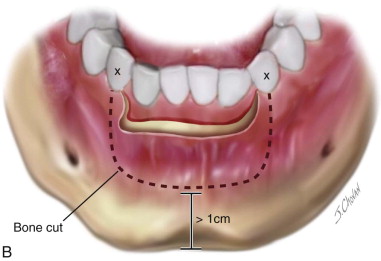

With a periosteal elevator, the soft tissue flaps defined by the sulcular incisions are raised in a subperiosteal plane, moving away from the tumor site. Care is taken to identify the mental nerves, which can be preserved unless this is oncologically unsafe. The flaps are extended to the midline bilaterally, passing inferior to the buccal gingival tissue previously outlined for resection. This exposes the buccal aspect of the anterior mandible to the chin ( Figure 100-1, B ).

Step 4:

Outline of the Osteotomies into the Mandible

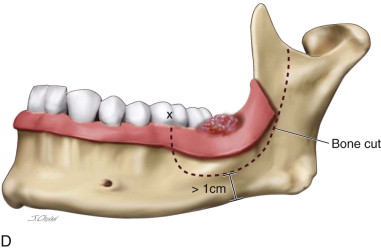

Any teeth that were preplanned for extraction to allow a 1-cm bony margin are extracted. The bony osteotomy is marked with a #2 side-cutting bur with a series of holes through the buccal cortex. The cut should be 3 to 4 mm beneath the apices of the teeth, and at least 1 cm of bone height should remain at the lower border. The corners of the cut where the vertical osteotomy meets the horizontal should be rounded to avoid a right angle, which could result in weakness, leading to stress fracture (see Figure 100-1, B ).

Step 5:

Performing Osteotomy

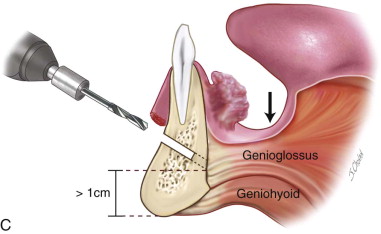

The osteotomy cut is made with either a #2 side-cutting bur or a banana blade reciprocating saw, depending on the surgeon’s preference. The bony cut is made at an angle, sloping lingually for a tumor located on the lingual side ( Figure 100-1, C ). The cut is made through both cortices. It frequently is difficult to be sure the entire lingual cortex has been cut, especially at the corners, and the osteotomy may require completion with gentle use of a mallet and thin osteotome to release the bony segment. Once the osteotomy is complete, the resected bone segment can be gently dislocated buccally, with care taken not to tear the lingual mucosa. The lingual gingiva and floor of the mouth can now be directly visualized and the lingual soft tissue resection completed under direct visualization. This is especially helpful in dentate patients with retroclined incisors.

Step 6:

Preparation of the Site for Reconstruction

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses