Dentofacial and craniofacial anomalies

9.1 Congenital anomalies

Aetiology

Cleft lip and palate disease ranges from a submucous cleft or bifid uvula to complete bilateral cleft lip and palate. The incidence is given in Box 9.1.

The craniosynostoses result from premature fusion of the craniofacial sutures and may arise sporadically when a single suture is involved or are inherited in the more complex syndromes. The diagnosis may be made according to the clinical presentation alone or involve molecular biological techniques to provide a genetic diagnosis now that access to such testing is more widely available.

Clinical management

Clinical management consists of the following phases:

Clinical examination

The clinical examination should include observation of:

The intraoral examination will look at:

• occlusion, including the use of wooden spatula between upper and lower teeth to check the level of the occlusal plane

Fig. 9.1 shows the occlusion of a patient with severe asymmetry owing to overgrowth of her left mandible.

Investigations

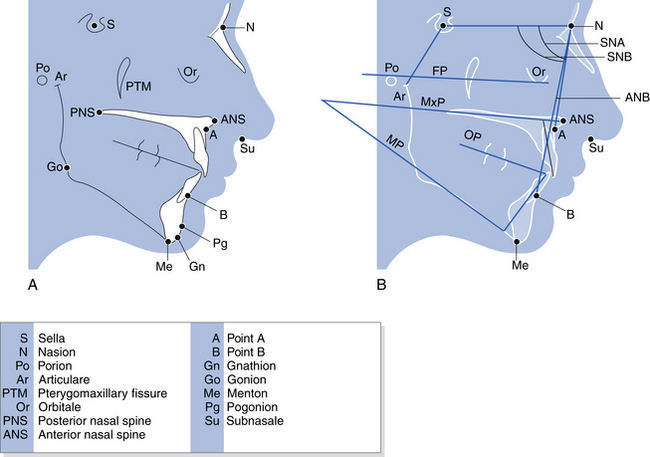

Cephalometric analysis: Lateral skull tracing for cephalometric measurements may be carried out manually with tracing paper and pencil or digitised tracing may be performed for computer-assisted analysis and operation planning. Radiographic landmarks are shown in Fig. 9.2 and also, the lines that are then drawn between some of these landmarks. The angles between these can then be compared with standard values to indicate facial skeletal variations from normal. Digital photographic images may also be superimposed on the radiographic images and surgical predications carried out with the computer software.

Diagnosis

For dentofacial anomalies, the diagnosis will describe the maxillary and mandibular base relationship relative to the skull together with a description of the dental occlusion and comments about general condition of the dentition and oral hygiene. The mandible and maxilla may be described as prognathic, hypoplastic or asymmetrical. The effect of these may be to produce a long face, open bite or short face. The chin may also be described using various classifications of excess (macrogenia), hypoplasia (microgenia) and asymmetry. For craniofacial anomalies, the diagnosis will also describe the orbits, eyes, ears and other features and may suggest various syndromes in a differential diagnosis.

Treatment planning

Treatment planning usually consists of the following:

• Preoperative orthodontic management to move teeth into a position for the best possible occlusion at operation. This may involve relief of crowding, flattening of the occlusal plane or other treatment.

• Surgery. Osteodistraction rather than traditional surgical techniques may have an increasingly prominent role in the future for some types of dentofacial and craniofacial anomaly.

9.2 Orthognathic surgery

Preoperative stage

1. A surgical plan is made to correct the abnormality described by the lateral cephalometric tracing. The surgically predicted outcome may be produced readily by computer software packages designed for this use and visualised on screen.

2. Model surgery is carried out on duplicate models and dental splints (occlusal wafers) are constructed for use during the operation to position correctly the bony fragments once osteotomised.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses