8

Other Single Teeth

Buccally displaced maxillary canines (BDC)

Mandibular canines

Mandibular second premolars

Maxillary second premolars

Maxillary first molars

Mandibular second molars

Maxillary second molars

Mandibular third molars

Impaction and crown resorption

Infra-occlusion of permanent teeth

Aside from third molars, the maxillary canines and central incisors are the principal teeth that may become impacted but, from time to time, other teeth may also be affected. For some of these teeth, familiar patterns emerge, typically affecting the same tooth and with the same aetiology in many of the cases. In others, unusual pathology is involved, which may affect any tooth or group of teeth and is, therefore, quite non-specific. Nevertheless, even with a widely heterogeneous group, trends may be recognized and treatment protocols may be suggested to cover a good proportion of them.

Before moving on to buccally displaced canines, there is a small group of maxillary canines which are neither buccally nor palatally displaced, but are in the line of the arch. According to the panoramic or periapical view, the orientation of their long axes is mildly mesially inclined. By virtue of this combination of location and angulation, the crown comes to be jammed at an angle against the distal aspect of the root of the lateral incisor, whose long axis may be oriented distally. From there, the canine appears to be unable to free itself to erupt, unless the incisor itself is tipped mesially during the initial space-opening procedure.

This standard preparatory orthodontic movement reduces the angulation between the long axes of canine and incisor to a marked degree, but it also moves the apex of the lateral incisor distally, providing the impetus to secondarily tip the crown of the canine distally and inferiorly and reduce the angulation still further. This will often be sufficient to elicit resolution of the impaction and spontaneous eruption of the tooth into its normal place in the arch.

In the event that progress is not achieved within a few months, simple surgery, attachment bonding and traction from an auxiliary nickel–titanium wire or elastic ligature will be sufficient to resolve the problem. The type of surgery advised will depend on the height of the impacted tooth vis-à-vis the gingival tissue. If there is a thick band of attached gingiva above the height of the unerupted tooth, then a simple window exposure will be ideal, since the tooth will be erupted through this band and a width of attached gingiva will remain on the labial side of the tooth in the long term. Should this not be the case, then an apically repositioned flap will ensure that the tooth will have a normal gingival attachment [1].

Equally, a full-flap closed procedure will achieve largely the same result as the apically repositioned flap procedure and, for these relatively minor impactions, there would appear to be very little to choose between the two procedures in terms of the periodontal outcome.

Buccally Displaced Maxillary Canines (BDC)

In Chapter 6, it was recorded that palatal impaction of maxillary canines occurs in 1–2% of most Caucasian populations studied. They exceed the prevalence of buccally impacted maxillary canines by a ratio of 2 or 3:1 [2, 3] while, paradoxically, buccally ectopic maxillary canines which have erupted into the mouth represent one of the most frequently encountered conditions in orthodontic practice. In contrast to Caucasian populations, one study [4] found that Orientals suffer more buccal impactions, while the frequency of palatal impaction in that ethnic group is very low.

Tooth size and arch length play important roles in the difference between palatal and buccal impaction, insofar as the dentition with palatal impaction is characterized by an excess of space in the dental arches for the most part [5–7], while the buccal impaction cases show marked crowding [5, 8]. In males this seems to be more due to a deficiency in length of the dental arch, while in females it was found to be more related to larger than average teeth [9]. We have pointed out that the developmental location of the unerupted maxillary canine is slightly buccal to the general line of the dental arch and that the two adjacent teeth erupt ahead of the canine. This being so, and in the presence of any crowding, the space for the canine between these two teeth will be reduced, and this will cause the canine to exaggerate the buccal tendency of its eruptive path (see Chapter 6).

Dental age also appears to be associated with these two very different phenomena. While patients with palatal canines showed a strong tendency for delayed dental development, a similar study of a large sample of patients with buccally ectopic canines showed a normal dental age distribution [10]. There was only a small variation on either side, when dental age and chronological age were compared. The dental age of patients with palatally impacted canines showed two distinct and separate trends. In half the cases, the dental age was normal, and in the other half, the dental development was very late, by as much as two years. Advanced dental development was not seen in any of the cases within the palatal canine group [11].

Ectopic Canines in the Absence of Crowding

Among the individuals that we see with buccal displacement of the canines, there is a small but significant number in whom there is no crowding to account for this phenomenon. In order to shed more light on this, the clinical features of the dentitions of a large sample of such cases were compared to those of a similar sample of BDC cases with crowding and another sample of cases in whom the canine had erupted into its place [12].

Dental age vs. chronological age and mesio-distal tooth dimensions showed no difference between the patients in the three groups. There was a single significant finding in this study, which related to the adjacent lateral incisor tooth. This tooth exhibited a much increased prevalence of anomaly and delayed development, in exactly the same way as has been recorded in relation to palatal canine displacement. Both the Guidance Theory and hereditary primary displacement of the tooth germ offer cogent aetiological explanations for the occurrence of this phenomenon, as pointed out in Chapter 6 (Figure 8.1).

Fig. 8.1 The canine has developed in an abnormal location – primary tooth germ displacement or lack of guidance from the adjacent peg-shaped lateral incisor?

In the absence of crowding, the canine may erupt higher up in the area of the sulcus oral mucosa, which creates a poor gingival attachment. From the periodontal point of view, having only thin oral epithelium covering the root leaves the patient with a delicate and easily traumatized attachment apparatus. Different surgical approaches have been described in Chapter 3 to resolve the problem.

Buccally Impacted Canines with Mesial Displacement

Most buccally displaced canines have a slight mesial displacement, overlapping the distal side of the lateral incisor. These are so common in orthodontics that we may consider them routine, whether they are erupted or unerupted. However, on occasion one may find that the degree of displacement of the unerupted canine crown is quite extreme, overlapping very high up on the mesial side of the root of the lateral incisor. These canines will progress more mesially and inferiorly in the early teen years and may be found at the level of the apical third of the root of the incisor in the bony depression that is located in the height of the sulcus. Although these are often palpable, the unusual height and mesial displacement of the tooth in the sulcus may lead to an erroneous initial clinical diagnosis.

In the clinical intra-oral examination, clues to their position may be found by studying the orientation of the adjacent incisors (Figure 8.2). Because the canines occupy bucco-lingual space in the alveolus, which is very narrow superiorly, their presence causes a palatal displacement of the root apex of the lateral and, occasionally, the central incisors. Tipping the patient’s head backwards and studying the anterior part of the maxilla from the occlusal aspect, the astute clinician will note that the lateral incisor has a strong palatal inclination, occasionally with its root prominently outlined beneath the palatal mucosa. The tooth clearly needs considerable labial root torque.

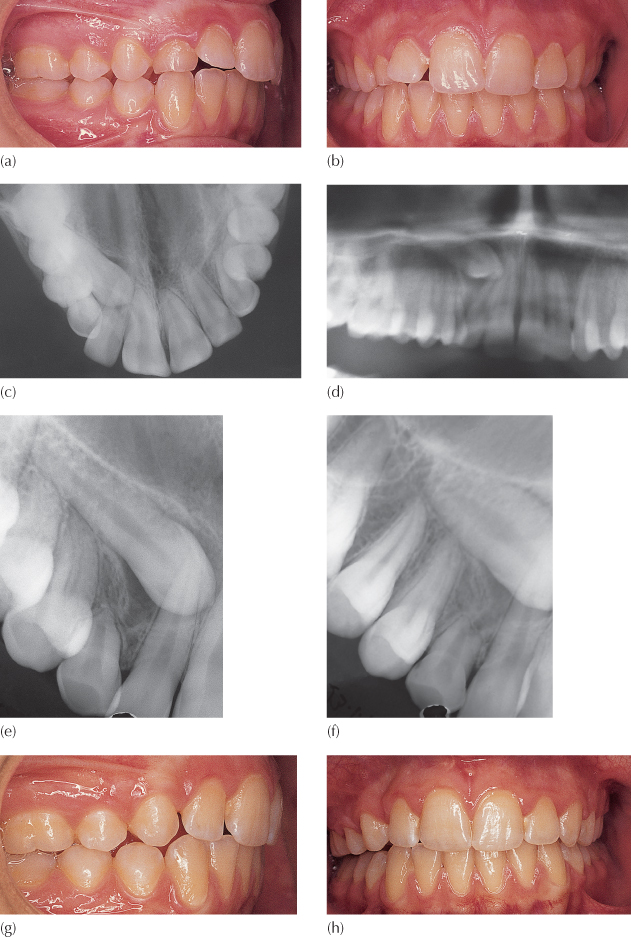

(a, b) Clinical views showing an over-retained deciduous right maxillary canine. Note the labial and distal tipping of the right lateral incisor crown and the palatal root position.

(c) Anterior occlusal view showing superimposition of canine crown and lateral incisor root on right side. From this view, the canine could be inferior to the lateral’s root on the palatal side or superior to the root on the labial.

(d) A section of the panoramic view to show the severe mesial displacement and unusual height of the canine. Taken together with the anterior occlusal view, the vertical tube shift created shows the canine to be buccal.

(e, f) Mesio-distal tube shift periapical views confirm the buccal diagnosis.

(g, h) Extraction of the right deciduous and permanent canines only, together with maxillary arch mechano-therapy, has achieved space closure and good intercuspation in class 1 on the left and class 2 on the right, with midline correction.

Diagnosis of labial location of the canine may not be easy to confirm radiographically. At this relative height, the panoramic view shows it to traverse the apical areas of the lateral and, sometimes, central incisors. Nevertheless, confirmation of labial location may be deduced given the presence of the tooth as it is imaged superimposed on the root of this lateral incisor and, from the clinical examination, the fact of palatally prominent root. Although the impacted canine is labial to the incisor roots, it is more distant from the film than are the incisor crowns, given its height and situation in the labial depression of the anterior maxilla and hence its radiographic image on the panoramic view will be enlarged, relative to those of the incisors. Canines in this location are precisely the teeth for which the method described for labio-lingual determination of canine position using a single panoramic view [13, 14] does not apply. Periapical or occlusal radiography of these teeth will superimpose them on the incisor roots at a lower level due to the acute angulation of the X-ray cone. Thus, the combination of a periapical or occlusal view with the panoramic view will facilitate diagnosis using vertical tube shift information (Figure 8.2c, d). Antero-posterior information will be seen on the lateral cephalogram, which will show the location of the crowns of these teeth relative to the incisor roots and to the anterior nasal spine.

When a mesially directed and labially impacted canine is present in a patient whose maxillary incisor arrangement accords with the archetypal class 2 division malocclusion, the situation may become a very complex canine/lateral incisor partial transposition. In this scenario, the unerupted canine lies high on the labial side of the root of the lateral incisor and, as pointed out above, the root of this lateral incisor is tipped palatally and its crown proclined labially. The long axes of the central incisors, on the other hand, show lingually tipped crowns and a labial orientation of their roots, which are often palpably outlined in the labial sulcus.

With the lateral incisor roots palpable on the palatal side and the central incisor roots on the labial, there is much space in the bucco-lingual plane between the root apices of these teeth. It will be appreciated that in these circumstances, the impacted canine may progress further mesially and migrate to the palatal side of the central incisor roots (Figure 8.3a–d). With the canine root labial to the root of the lateral incisor and its crown palatal to the central incisor, orthodontic resolution and alignment may be impossible.

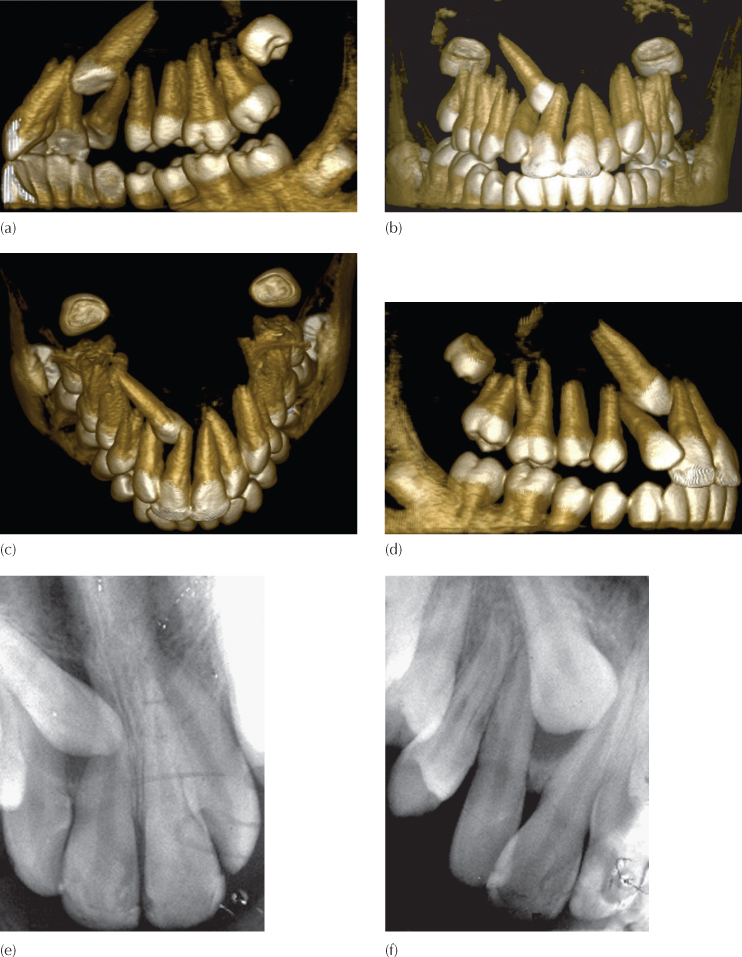

Fig. 8.3 (a–d) Three-dimensional CT views of the anterior maxilla, showing a high buccal canine that has displaced the lateral incisor root palatally and distally and which has progressed mesially to traverse the arch on the palatal side of the central incisor. (e, f) The two tube shift periapical views confirm the palatal location of the canine crown vis-à-vis the central incisor, but give no hint as to the complexity of the case. A palatal approach to surgical exposure would be disastrous (see Figures 12.16, 12.17 and 12.18).

(Courtesy of Dr N. Dykstein.)

If positional diagnosis is based solely on the buccal object rule using two periapical films at different angles, the palatal location of the canine crowns to the central incisors will be confirmed, but without clinical observation or more sophisticated imaging the relation between canine and lateral incisor will be missed. The unsuspecting orthodontist, who routinely relies solely on Clark’s tube-shift method (Figure 8.3e, f), will surely offer inappropriate treatment in this case because it will lead him/her to think of a palatal surgical and orthodontic approach to the crown of the canine. This would be totally misleading since the subsequent orthodontic manipulation of the canine in a palatal direction will hinge the canine root around the root of the lateral incisor, inflicting damage to that tooth. At the same time, the apex of the canine will be swung anteriorly to clash against the labial plate, from where there would be no reasonable possibility of success. The only available approach would be to expose the canine crown from the labial side and apply traction in a labial and distal direction to bring the tooth clear of the central incisor. It would then need to be drawn labially and distally around the root of the lateral incisor and into its place in the arch.

Nevertheless, a treatment decision will still be necessary since the canine will not remain static, but will continue on its ectopic path. The treatment options are:

1. To leave the canine in place – with suitable long-term radiographic follow-up planned; this policy precludes any possibility of orthodontic correction of the incisor relationship and it always carries with it the risk that neglect on the part of the patient will lead to further complications in later life.

2. To extract the impacted tooth and align the lateral incisor.

3. To extract the lateral incisor, align the canine into its normal place and prepare for an implant to replace the missing incisor.

4. To extract the lateral incisor, align the canine into the place of the missing incisor and draw the posterior teeth mesially to eliminate the spaces.

5. To align the teeth in their transposed order.

6. To expose the tooth and bring it into designated place in the arch, while realigning the lateral incisor in its place, with carefully planned directional orthodontic treatment.

Regardless of its relation to the central incisor, a labial surgical and orthodontic approach is essential because of the relationship of the canine to the lateral incisor. Surgical access and orthodontic traction need to be negotiated very delicately between the roots of the central and lateral incisors and, above all, no attempt at root uprighting or torque of the incisors should be undertaken until the canine is well clear of both (Figure 8.3). This, therefore, rules out the early use of rectangular archwires and it is often wiser not to ligate the lateral incisor into the arch until the later stages of treatment. In these cases, the canine has to be drawn through between the incisor roots at a level high in the sulcus, above to the labial archwire, which makes it difficult to erupt it through attached gingiva (Figure 6.45).

The three-dimensional relationship of the teeth to one another and the possible existence of incisor root resorption are very difficult diagnoses to make, particularly in the bucco-lingual plane, as pointed out in Chapter 2, and cone beam computerized tomography should be performed to provide the relevant and much needed accurate information.

For most other buccally impacted maxillary canines surgical access is good, but the ability to provide a satisfactory orthodontic strategy to reduce the impaction and still provide for a good periodontal prognosis may be poor. This is because the high buccal canine tooth must be brought buccally, inferiorly and distally in a manner that circumvents the root of the adjacent incisor. This involves its being drawn in a semicircular flanking movement around the lateral incisor root, in an area where the alveolar bone is too narrow to allow one root to pass by another. As the canine is moved labially, the bony alveolar plate responds and becomes more prominent as it remodels labially.

This bony remodelling does not add width to the same degree as the dental movement, so that the root of the tooth loses some of its labial bone and soft tissue support, and a long clinical crown often results. The prospects for muco-gingival surgery, performed at the time of exposure while possible [15, 16] are very limited for the high buccal canine and a long clinical crown with a relatively poor periodontal outcome are to be expected [17].

Given these drawbacks, the more severely displaced buccal canines of this type may occasionally need to be extracted, and, as far as possible, the deciduous canine left in place. In this instance, it is recommended to provide additional space mesially and distally, to allow for its crown to be prosthetically enlarged in anticipation of a later implant restoration when the deciduous tooth is finally lost. If the deciduous canine has a poor prognosis, an early decision regarding space closure or space opening should be made. Where appropriate, controlled orthodontic space closure may then be carried out, with or without a compensating extraction on the opposite, unaffected side. Alternatively, orthodontic preparation of the case for an implant-borne replacement crown will need to be undertaken as part of the overall orthodontic treatment.

Buccally Impacted Canines with Distal Displacement

It is unusual to come across a buccally located canine which is also displaced distally. These are almost invariably transposed with the first premolar tooth, to a greater or lesser extent (Figure 8.4). Many of these transposed canines erupt high in the sulcus where they are invested with oral epithelium rather than with attached gingiva. Others do not erupt and may need to be surgically exposed, depending on the orthodontic treatment plan. However, in these cases the orthodontist will frequently decide to align the teeth in their transposed order. By and large, these transposition patients present with the first premolar crown in its normal place, but its roots are displaced mesially, giving the tooth a distally inclined long axis. The tooth may be quickly tipped mesially, uprighting it into the site vacated by extraction of the deciduous canine. Under these circumstances, tipping the first premolar into the canine location reciprocally creates space for the canine in the first premolar place and the canine will usually respond with autonomous eruptive movement.

Fig. 8.4 A distally displaced maxillary canine, transposed with the first premolar.

Many of these teeth may then come down without the application of orthodontic forces, although full eruption may take many months, sometimes extending into a year or more. Nevertheless, and even though there may be no apparent reason for this natural process to be retarded, a good number remain unerupted or in their partially erupted state for a very long time and hardly progress. Therefore, following the mesial movement of the first premolar in the earlier part of the treatment, these teeth should be exposed and actively drawn to the labial archwire, using light elastic traction or an auxiliary nickel–titanium wire placed piggyback style over the existing heavier base arch. Leaving an orthodontic appliance in place for all this time without exploiting it to erupt and align the canine is counterproductive, insofar as its presence runs the risk of producing the deleterious side-effects of caries and periodontal inflammation and is to be discouraged. Thus, when the impacted tooth shows no signs of erupting or does not fully erupt within a reasonable period of time after space has been prepared for it, orthodontic traction and alignment should be initiated.

If the tooth remains unerupted and situated above the level of the line of the attached gingiva, the window technique exposure will leave it with an undesirable labial attachment consisting of oral mucosa. Consequently, an apically repositioned flap or a fully closed flap exposure will be more appropriate, and the tooth brought down by direct traction to the labial archwire of the appliance. Many clinicians tend to judge severity of transposition by the relative positions of the crowns of the two affected teeth, when the only valid determinant of severity is in the relative positions of their root apices. As the result, the inexperienced practitioner may be unwisely drawn into attempting to bring the teeth to their ideally corrected order – a task that requires considerable clinical skill and an extended treatment time.

If the displaced canine can be moved mesially while it is still relatively high, then the danger of root proximity of the affected teeth, as they are drawn past each other across the narrow alveolar width, is reduced. However, while a closed surgical exposure may be preferred with a high canine, this can only be conveniently used when the direction of traction is vertically downwards. It is not easy to adapt the method when the direction of traction has more than a minor degree of mesial or distal component, because the elastic thread or closed coil spring that may be used will cause soft tissue impingement.

Nevertheless, if full correction of the transposition is to be undertaken, it is wise initially to place an eyelet attachment on the mesial aspect of the exposed canine, so that mesial traction will not generate a mesio-lingual rotational component on the tooth as it moves forward. Once the crown of the tooth has been moved into its correct location, the eyelet is removed and a bracket of the type used on the other teeth is placed in its ideal position on the tooth to complete the remaining movements needed, usually mesial uprighting, palatal root torqueing and a degree of de-rotation.

Mandibular Canines

Mandibular impacted canines are rarely seen and, as the result, the more bizarre cases are published as single case reports in the literature [18, 19]. The very few numerically significant case series that have been published have gathered the cases from many centres and individual practitioners, on an international multicentre basis [20].

Impacted mandibular canines are usually chance findings and are not discovered because the condition is almost always symptomless. The over-retained deciduous canine may not raise the suspicions of a dental practitioner until well into the second decade of life and often even later. It seems possible that females are more frequently affected, although the evidence for this is tenuous, given the lack of large sample studies. The frequency with which this phenomenon occurs has been quoted as being 20 times less frequent than the parallel condition in the maxillary arch. While maxillary impacted canines crossing the mid-palatal suture has not been reported, mandibular canines do cross the symphysis (Figure 8.5) and have been reported to have reached as far as the permanent molar on the opposite side [21, 22].

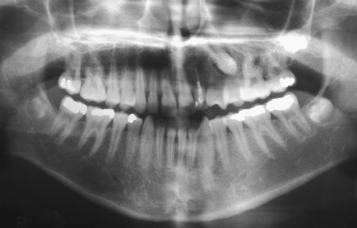

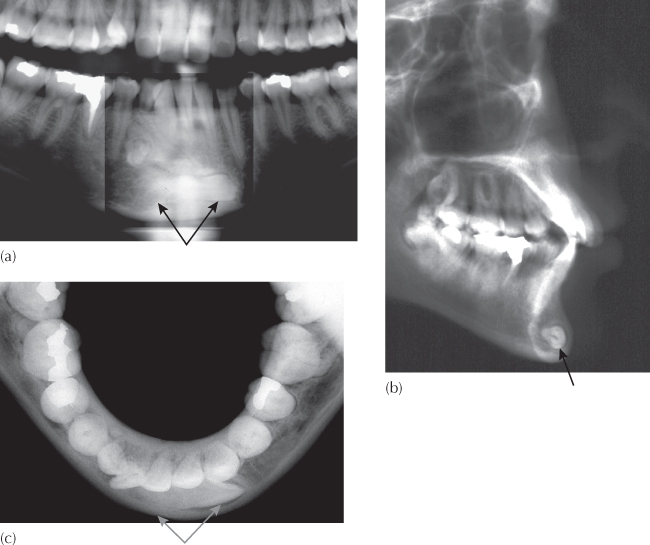

Fig. 8.5 The crown of the horizontally impacted right mandibular canine overlies the root of the erupted mandibular canine of the opposite side.

(Courtesy of Dr T. Weinberger.)

They may sometimes be located on the lingual side of the alveolar process, when they will appear as a palpable hard swelling under the lingual mucosa. They are more frequently to be found buccally ectopic or in the general line of the arch. They travel relatively large intra-osseous distances and may become embedded in the chin prominence.

The first clue to the existence of an impacted canine is the over-retention and lack of mobility of its deciduous predecessor and this should stimulate the clinician to perform a radiographic examination.

Regarding aetiology, there may be obvious local factors to which the condition may be attributed, namely supernumerary teeth, odontomes (Figures 8.6 and 8.7) and an enlarged dental follicle. However, it is important to note that soft tissue lesions, such as expanding radicular cysts that may have developed from non-vital deciduous first molars or canines, are potent displacing agents for developing adjacent teeth (see Figure 11.7). Nevertheless, for most of these cases, including the extreme examples, there is no apparent local cause and it seems likely that a hereditary primary tooth germ displacement may account for the abnormal angulation of the long axis of the tooth [23]. If this angulation is between 30° and 50°, there is a good chance that the tooth will migrate across the midline in a relatively short period of time, while an angle in excess of 50° will make this eventuality virtually certain.

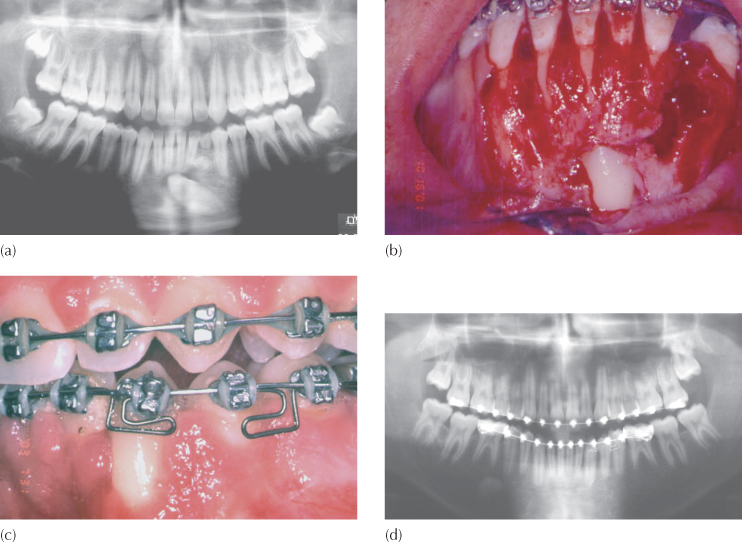

(a) The left mandibular canine has been grossly displaced distally and inferiorly because of an odontome, and is in close association with the lower border of the mandible.

(b) A true occlusal view of the canine/premolar area.

(c) After alignment and space-opening, surgical removal of the over-retained deciduous tooth and odontome has permitted attachment placement.

(d) Rapid improvement in position has occurred. Note the deleterious effects on archform and midline due to the use of a base arch of inadequate gauge.

(e) A periapical view in the latter stages of resolution. Note that the tooth has responded well, despite having been covered with repaired and calcified bone after attachment bonding at the time of the closed exposure.

Fig. 8.7 (a) Panoramic view of the mandible with mental region – the contrast of the mid-section over the chin has been altered to show the horizontally impacted canine, with compound odontome. (b) Cephalometric radiograph shows the canine to be completely horizontal and at 90° to the mid-sagittal plane and the film. (c) Occlusal view of the anterior mandible.

Although there is some anecdotal evidence alleging a remarkably high speed of migration of these teeth, this is difficult to assess since these cases are usually seen post-factum and, even when seen before much of the movement has occurred, most patients will be advised to have interceptive or corrective treatment. Few will be merely kept under observation (i.e., supervised neglect!), given that a worsening of the situation seems inevitable.

Interceptive treatment should generally be instituted as soon as the anomaly is discovered. The extraction of the deciduous canine may exert a positive influence to alter the orientation of the aberrant permanent canine. By also extracting the first deciduous molar, the first premolar may often be influenced to erupt early, assuming it has about half of its expected root development. This will have the effect of providing more space in the alveolar bone distal to the canine because, with the eruption of the tooth, the broader diameter of the crown will have given way to the narrower root diameter adjacent to the canine. Removing a non-vital deciduous canine or first molar, particularly if these had been associated with an unresolved granuloma or with cystic change, may encourage a dramatic improvement (see Figure 11.7).

When a canine has progressed beyond the mesial side of the lateral incisor, the majority of authorities have advised extraction of the canine itself, leaving the deciduous canine in place. Alternatively, if the case is considered to be an orthodontic extraction case, this tooth will be tagged for extraction rather than the more usual choice of a premolar.

Corrective orthodontic treatment may seem to be the best choice, but this is likely to be disappointing, particularly if the tooth is on the labial side and has migrated mesially, which essentially means that it has developed into a transposition. Good 3-D imaging of the area will be necessary in order to decide if orthodontic treatment can provide a good answer. The periapical radiograph will most often provide adequate qualitative information regarding the mandibular canine, unless it is very deeply displaced. This is because it may not be possible to insert the film sufficiently deeply into the lingual sulcus. In these cases, a panoramic view may provide a better view of the tooth and its mesio-distal orientation. A true occlusal view will be required to provide the third dimension needed to accurately localize the tooth and it is important to remember that the central ray of the X-ray machine should pass along the long axes of the mandibular incisor teeth for this view to be of value. In the midline region, the missing aspect will be depicted on the lateral cephalogram that will have been taken to assist in the diagnosis and treatment planning of what initially appeared to be routine orthodontic treatment (Figure 8.7). In this type of case, extraction may sometimes be the only practical line of treatment. Given the presence of the roots of adjacent teeth immediately superior to it and the narrow dimensions of the mandibular body in this area, there may be inadequate room for successful orthodontic manoeuvre, particularly when a partial or complete transposition of teeth is to be corrected. A parallel anomaly occurring in the maxillary arch will usually be much more amenable to treatment, because the impacted tooth may be temporarily moved from the narrow alveolar ridge inwards into palatal bone to permit the movement of an adjacent tooth.

For most of the impacted mandibular canines, however, the radiographic evaluation will indicate a reasonable prospect for orthodontic alignment. In line with the general principles set out in Chapter 4, an orthodontic appliance is placed and space is prepared in the arch to accommodate the tooth before its exposure is undertaken.

Lingually impacted mandibular canines will almost invariably be found with their root apex in their normal location and the lingual displacement of the crowns of the teeth is due to an abnormal orientation of the long axis – a tipping displacement. Therefore, orthodontic realignment involves merely a corrective tipping movement of the crown in a buccal, extrusive and, possibly, distal direction. The tooth should be exposed, an attachment bonded to the buccal aspect and the wound fully closed with the sutured flap, unless the tooth is very superficial. In this way, traction from the attachment direct to the labial archwire is all that is needed to bring it to its place. The wire ligature pigtail, tied to the bonded attachment at the time of surgery, is rolled downwards to form a loop, close to the sutured gingival tissues. An elastic chain is placed across the span between first premolar and lateral incisor, and its middle portion is stretched downwards with a haemostat or ligature director and ensnared in the rolled down pigtail. This provides a light, easily measurable and vertically directed force on the impacted tooth, with a wide range of action. Alternatively, an auxiliary nickel–titanium wire may be passed through this rolled-down pigtail and through the brackets of a number of teeth on each side, under the main arch, to achieve the same effect.

Migration, Transmigration and Transposition

Mupparapu [21] has attempted to classify buccal canines – teeth that are remarkably prone to the most bizarre eruptive movements – into five types, as follows:

1. Mesio-angular, lying inferiorly to the front teeth and, with its crown crossing the midline and termed a transmigrated tooth.

2. Impacted horizontally below the apices of the incisors.

3. Erupted mesially or distally to the contralateral canine.

4. Impacted horizontally below the apices of the contralateral canine and premolars.

5. Vertical, coinciding with the midline. It is the only type which may be declared a true transposition ab initio, rather than as the result of migration.

A special case, therefore, must be made for the buccally displaced mandibular canine, migrated, transmigrated or transposed mesial to the lateral incisor. Although very uncommon, it is the most frequent form of transposition in the mandible, aside from third molars. The crown of the canine will need to be moved buccally in order to sidestep the lateral incisor root, before being moved towards the archwire. As with the parallel situation in relation to the buccally displaced maxillary canine, the orthodontic and periodontic prognoses of treatment for these teeth deteriorate in inverse relation to the amount and type of mechano-therapy used. Nevertheless, in a minority of these patients, full resolution of the transposition may be successfully achieved provided the cases are carefully selected, taking into consideration the periodontal prognosis, in addition to the biomechanics.

In theory, it is possible to apply appropriate tipping and bodily movements to move the tooth back from whence it has clearly come. However, the more horizontal the tooth, the greater will be the need for a large component of force being applied through its long axis – a horizontal ‘intrusion’, which is clearly futile. The tooth will also need to be drawn below the incisor apices with its crown exposed in highly mobile mucosa and in the deepest part of the labial sulcus. Even the more amenable mesially migrated canines will need to be drawn distally and occlusally, but also laterally in order to skirt the roots of one or more incisors. Once the crown of the tooth has been brought to its place in the arch, the canine root must be distally uprighted and finally lingually torqued to an appreciable degree. Given in the best circumstances, it will be appreciated that it is unlikely there will be much bone covering the root on the labial side of the treated tooth, its clinical crown will be long and the marginal soft tissue on the labial side will be largely devoid of attached gingiva. Treatment will have been inordinately long to achieve an acceptable orthodontic result, but it will be accompanied by a poor periodontal outcome (Figure 8.8).

(a) A transmigrated mandibular left canine has traversed the midline, with over-retained deciduous canine and odontome.

(b) At surgical exposure, the canine is located inferior to the right central incisor and is situated below the depth of the sulcus.

(c) In the final stages of orthodontic treatment aimed at completing the uprighting of its root and lingual root torque, the clinical crown is very long due to gingival recession and there is deep periodontal pocketing on the mesial side of the canine.

(d) Root paralleling of the teeth is good, but apical root resorption is present on all teeth carrying orthodontic attachments. There is crestal bone loss in the immediate area of the affected canine. The periodontal prognosis of this tooth contrasts sharply with the success of the orthodontic treatment.

There remain three additional and alternative lines of treatment for the non-crowded case. The clinician may:

1. extract the canine, leaving the deciduous canine in its place, provided its root is of reasonable length and prognosis;

2. extract an incisor and align the canine in its place, leaving the deciduous canine in place;

3. align the two teeth in the transposed relationship which, in the mandibular arch, may offer the optimal solution [24–27].

In the presence of crowding, extraction of the deciduous canine and the adjacent permanent incisor, or of the deciduous canine and the permanent canine, should be considered in addition (or in preference) to a more conventional choice. The space provided may then be used for the relief of crowding as an integral part of a comprehensive orthodontic treatment programme that includes other aspects of the malocclusion.

One final thought in regard to transmigrated mandibular canine relates to its innervation. It should be remembered that, regardless of the distance it travels, the tooth takes with it the blood vessels and nerve supply with which it started out life. This needs to be taken into account when considering the surgical exposure or removal of the tooth under local anaesthetic cover.

Mandibular Second Premolars

Crowding and Space Loss

Perhaps the most common cause of impaction of the second mandibular premolar is the early extraction of its deciduous predecessor, although this has become less common with the decline of caries in the Western world. With the loss of the second deciduous molar, the adjacent permanent molar will usually tip mesially and ‘roll’ lingually. Additionally, there will be a degree of distal drifting of the first deciduous molar of the same side, but total elimination of the space for the second premolar does not often occur. The result will be that this successional tooth will be blocked from erupting into the line of the dental arch. Given that its early developmental position is slightly lingual to the line of the arch, and that it is prevented from migrating upwards in the normal manner, it either will move more lingually and erupt on the lingual side, or it may remain impacted and beneath the ‘pitched roof’ formed by the two adjacent erupted and tilted teeth.

The radiographic method for these cases is very similar to that described for mandibular canine teeth. The periapical film is used to provide detail but, in the mandibular premolar area, it also provides a lateral horizontal view in this area. In theory, therefore, it may be supplemented by an occlusal view to provide the third dimension and enable accurate localization. Unfortunately, the occlusal view has the X-ray beam passing through the full thickness of the body of the mandible and, unless the tooth is markedly displaced to the lingual or buccal side it will not be possible to differentiate it from the mass of bone. If its presence can be confirmed in the periapical view and there is no clear view of the outline of the tooth on this film, it will be safe to assume the tooth to be close to the line of the arch and undeviated buccally or lingually.

Alignment requires space, and this may be achieved by re-siting the drifted teeth back in their former or improved positions using a fixed orthodontic appliance with a coil spring. This may often require intermaxillary (class 3) traction to reinforce the anchorage of the lower jaw and to prevent undesirable incisor proclination.

Alternatively, extraction may sometimes be necessary, in which case the impacted tooth or its immediate premolar neighbour may be the tooth that will be sacrificed along with a matching tooth in the other three quadrants of the mouth, in order to treat the overall malocclusion. Given space by distal movement of the molar and/or by mesial movement of a distally tipped first premolar or by extraction of the adjacent premolar, an impacted premolar tooth will normally erupt with considerable speed without further assistance.

From the periodontal point of view, surgical removal of unerupted mandibular second premolars, which may be needed in an extraction case, may leave a marked bony defect in the area, even after the excess space has been closed and adjacent teeth have been fully uprighted. This may be accompanied by a deep mucosal fold or cleft in the interproximal area in the site where the extraction had been made. This may disappear once space closure has been completed, although it may persist and thus prevent the regeneration of bone in the interproximal area, to cause a periodontal defect.

Abnormal Premolar Orientation

The second deciduous molar of the lower jaw has much to answer for in relation to the non-eruption of its permanent successor, not merely when it is prematurely lost due to the ravages of caries, but also when its presence is abnormally prolonged. The second premolar tooth germ is not always in its ideal developmental position, directly between the mesial and distal roots of the deciduous molar. Indeed, an abnormal angulation or location seems to be a frequent finding.

The premolar may often be tipped more distally, initiating resorption of only the distal root, leaving the mesial root of the deciduous molar largely intact. This will lead to over-retention of the deciduous tooth, often despite the complete disappearance of the distal root and much of the coronal dentine. A periapical radiograph will show the long-rooted premolar very superiorly positioned, almost inside the distal part of the crown of the deciduous tooth, whose long and thin spicule of the mesial root remains, grimly resisting exfoliation. A parallel scenario may occur with resorption of the mesial root due to mesial tilt of the second premolar from early on in its development, although it seems to enjoy a lesser frequency. In either of these cases, as long as the degree of tilting is relatively slight and the tooth is relatively high up in the alveolus, the extraction of the deciduous tooth will usually suffice to achieve the rapid and trouble-free eruption of the premolar tooth. Space is never a problem in these cases, since the second premolar has a smaller mesio-distal crown width than its healthy predecessor.

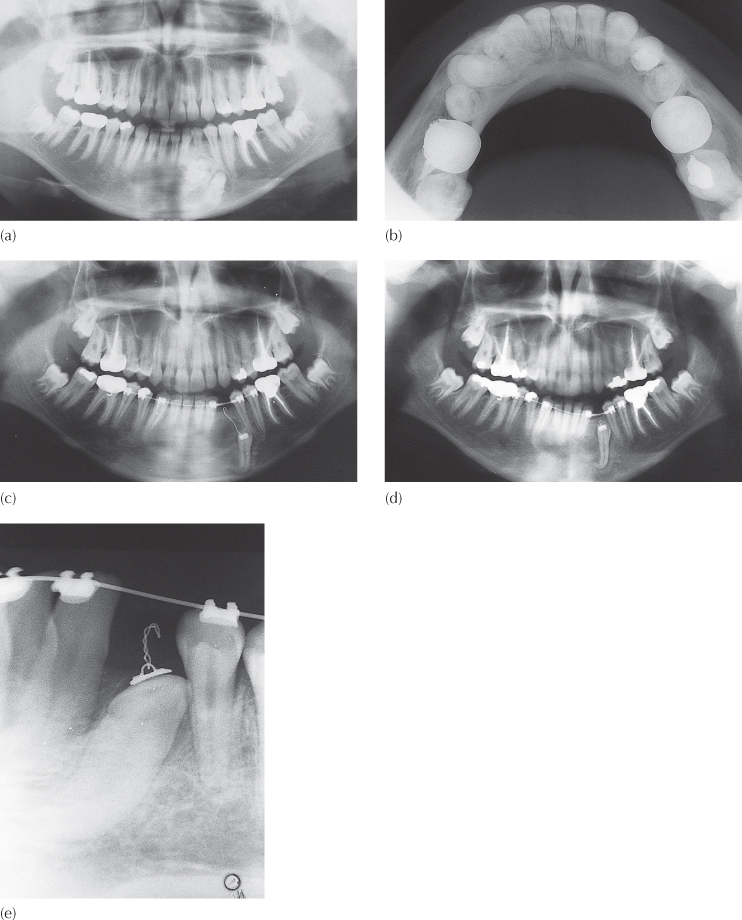

A premolar tooth which has a stronger distal tilt is usually situated more apically, and the distal-occlusal aspect of its crown is in close relation with the mesial root of the first permanent molar. The second deciduous molar is usually over-retained at the time of detection and more than adequately holding the space in the arch (Figures 8.9 and 8.10).

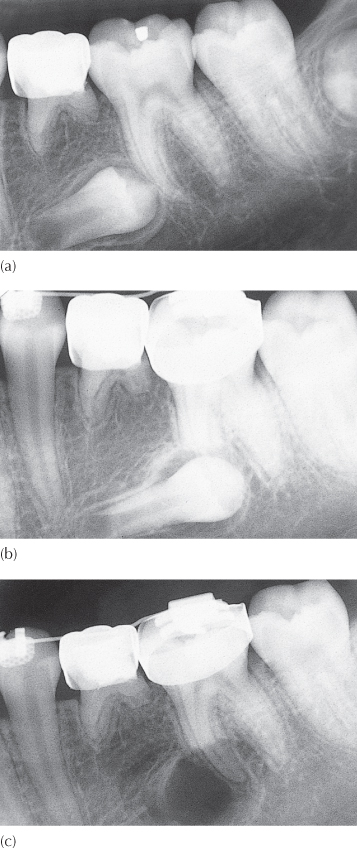

Fig. 8.9 (a) A late-developing left second premolar, horizontally oriented. (b) A year later, the tooth has moved distally to overlap the mesial root of the first permanent molar. (c) Extraction reveals some resorption of the mesial root of the molar.

(Courtesy of Professor Y. Zilberman.)

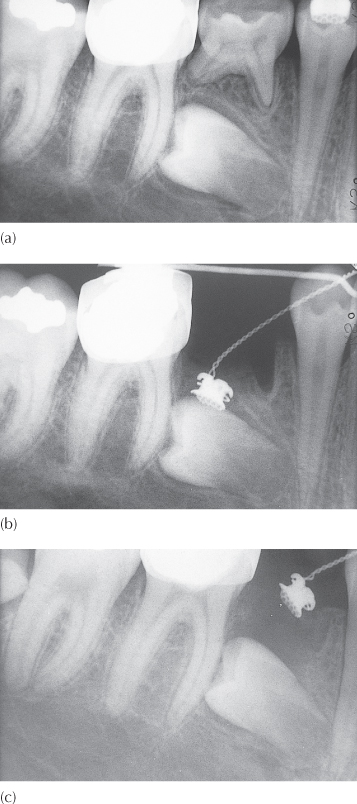

Fig. 8.10 (a–c) Serial periapical views of a failed attempt to bond an edgewise bracket to an inadequately developed second mandibular premolar.

(Courtesy of Dr D. Harary.)

In terms of aetiology, it has been found that an exaggerated disto-angular malposition of the unerupted mandibular second premolar is associated with agenesis of its antimere [28] and with retarded dental development. In Chapter 6, we have alluded to the existence of a connection between second premolar anomaly and palatally displaced canines, which are similarly affected by late development. It seems that individuals with both maxillary canine and mandibular second premolar anomalies suffer greater delay in dental development [29].

In these cases, a space-holding device should be used when the deciduous molar is removed to prevent tipping of the permanent molar, and an attempt may also need to be made to upright the premolar. An appropriate space-maintaining device may be designed in many ways, but, classically, a buccal and lingual bar may be soldered to two bands to form a simplified fixed bridge, which is then cemented to these teeth. Alternatively a single rigid bar, with terminal loops or a mesh pad at each extremity, may be bonded to the buccal surface of the first molar and first premolar. This is a fairly good alternative provided it is well clear of the occlusion, although it may still become debonded by occlusal forces transferred through bulky and hard foods. Because of its small size, the debonded bar with terminal loops on a mesh pad presents a potential hazard, since it may be ingested or, worse, inhaled by the patient.

At surgery, only the mesial and occlusal aspects of the impacted and distally tipped premolar tooth are exposed and, where possible, an eyelet should be bonded to this area of the crown of the tooth, carrying a twisted steel pigtail ligature. The tooth is fairly deep down and an open exposure is likely to leave the mesial root of the first molar exposed and devoid of attachment. For this reason, the flap should be completely sutured back into its place and the stainless steel ligature wire pigtail, ligated through the bonded eyelet, becomes the means of applying force to the unerupted tooth.

An elastic chain may be stretched between a hook on the fixed band of erupted first premolar and first molar, parallel to and overlying the rigid bar. Once in place, the middle of the elastic chain is drawn downwards with artery forceps and ensnared in the pigtail ligature to apply a vertical erupting force to the impacted tooth. The greater the degree of movement required, the more substantial must be the anchor base, and, where indicated, a fixed lingual arch to the opposite molar may be advisable.

This region of the mouth does not provide easy access to permit acid etch bonding and, particularly when the orthodontist is not present to do this part of the surgical procedure, eyelet attachment may not be possible (Figure 8.10). When this is the case, more radical surgical compromises may have to be made in order to salvage the tooth. Wider exposure is indicated and a buccal or lingual extension to the exposure may be needed, depending on the orientation of the tooth (Figure 8.11). This will then hopefully provide the needed access for bonding the attachment, with a satisfactory degree of reliability.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses