5

Esthetic periodontal treatment

A harmonious smile does not just depend on beautiful lips. It cannot be conceived without a perfectly healthy gingival frame and well-aligned natural teeth. Since the smile is a vital part of a beautiful face and there is a high patient demand for beauty, demands for smile enhancement with periodontal surgery, cosmetic restorations, or implant restorations continue to increase as patients live for longer.

The fundamental criteria of dentogingival esthetics are perfectly established and must be a part of the esthetic culture of every clinician. Each practitioner must adopt a scientific approach when analyzing dentogingival esthetic criteria, to establish the main alterations that are needed to their patients’ smiles before proposing orthodontic, surgical, and/or restorative solutions.

The biological rationale

If the goal of a clinician is to reduce the depth of periodontal pockets, surgery remains the treatment of choice for moderate to deep pockets (4–6 mm and > 6 mm). But if the goal is to gain a clinical attachment, root planing without raising a flap will yield better results than root planing with flap raising for pockets with little to average depth (1–3 mm and 4–6 mm). On the other hand, for deep pockets (> 6 mm) and esthetic gingival concerns, it is the surgical approach that will allow the pocket depth to be reduced and esthetic problems to be resolved (Heitz-Mayfield, 2000).

According to Claffey et al. (2004), surgical and nonsurgical therapies achieve similar results in terms of overall improvement of clinical conditions, and allow clinical attachment levels to stabilize within the context of regular follow-up therapy and with good personal plaque control.

The logic of active periodontal treatment today is therefore based on the association of four phases (Range, 2008) (Figs 5.1a–d):

- Initial therapy: to reduce inflammation by means of mechanical debridement and chemical irrigation.

- Reevaluation: to measure the patient’s response and weigh the risks and benefits of possible surgical treatments.

- A possible corrective phase: to reduce the pockets if they pose a risk of progression of the disease. Resective procedures will reestablish a positive periodontal structure compatible with a high level of plaque control, and/or regenerate infra-bony lesions, cover gingival recessions, and finally correct ridge deformities.

- Maintenance therapy: to reinform the patients about the disease, reinforce the patient’s oral hygiene, eliminate etiologic factors, regain dental health, and prevent recurrence of disease.

It is important to understand the essential role of dental hygiene, because the absence of, or a deficiency in, dental hygiene induces more bacteremia than the surgery itself. The prescription of antibiotics cannot compensate for a lack of dental hygiene (Lesclous, 2011).

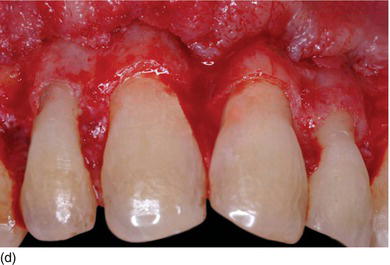

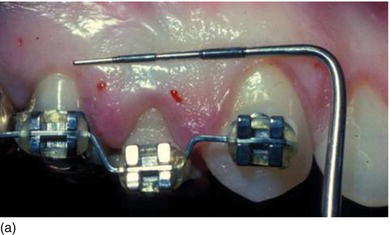

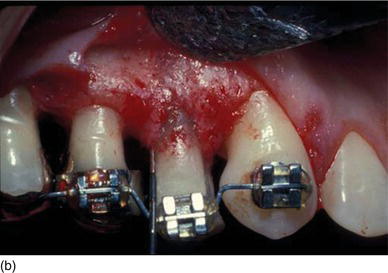

Figure 5.1 (a) The patient at the initial consultation, with gingival inflammation. (b) The healthy aspect of the gingiva 6 weeks after initial preparation. (c) Multiple gingival recessions on the left maxillary arch showing the instrument used for the incision and then raising the flap. (d) The healthy aspect of the gingival margin and interproximal papillae 3 months later.

The composition of an esthetic and functional dentoalveolar gingival unit (DAGU) or periodontal restorative interface (PRI) must take into account the periodontal health of the gingiva, the bone, the interdental papillae, and the biological space. Periodontal therapy is concerned, first and foremost, with maintaining the health of periodontal structures and correcting any gingival disharmony to achieve a balanced gingival contour for each smile.

Disharmony in the gingival contour can be easily managed with periodontal plastic surgery through resective (gingival smile), additive, orthodontic, or biological procedures (gingival recession), but this treatment is much more challenging in implant surgery because of the differences between the tooth and implant surfaces. Eventual periodontal corrections cannot be envisioned without evaluating the position of the mucogingival line, the height and thickness of the keratinized gingiva (KG), the sulcular depth, the position of the interdental papillae, and the level of the alveolar crest (Levine and McGuire, 1979). Therefore, visual precision – without any guesswork or estimation based on emotional considerations – is vital for successful, predictable, and cost-efficient treatment.

More recently, instrumentation such as Chu’s Aesthetic Gauges (Hu-Friedy Inc., Chicago, IL) has been created to diagnose and predictably treat esthetic tooth discrepancies and deformities. These new probes could also evaluate clinical and anatomical teeth dimensions, and could now secure the treatment through the application of quantitative standards (Chu, 2007):

- The metallic gauge helps to provide quick and simple analysis of the osseous crest location midfacially and interdentally. It has a deliberate curvature of the tip, which is coincident with the curvature of the tooth and root. This allows easier negotiation of the osseous crest location, particularly in the thin biotype. This increased dimension allows greater stability and confidence during the sounding process. Chu’s metallic gauges can be used repeatedly to determine the amount of midfacial osseous tissue to be removed during surgery (see Figs 4.12b, c).

- The T-bar gauge is used to measure a noncrowded anterior dentition and the In-line gauge is used for a crowded dentition (see Fig. 4.19h).

- The measurements are mathematically aligned, with a preset individual tooth proportion ratio of 78%. The practitioner can accurately and simultaneously evaluate the length (vertical arm) and width (horizontal arm) and, therefore, visually assess the correct tooth size and proportion, before, during, and after the surgical crown lengthening procedure.

- The Crown Lengthening Gauge, or In-line gauge tip, is designed to measure the midfacial length of the anticipated restored clinical crown and the length of the biological crown (i.e., from the bone crest to the incisal edge). The short arm of the In-line tip is of the same length and cross-section as the long arm of the T-bar tip (see Fig. 4.19i).

- The color-coded marks on the shorter arm represent the clinical crown length, and the corresponding color markings on the longer arm represent the biological crown length at the bone level.

During the osseous resection procedure, the visualization of these two parameters compels the clinician to focus on the end-goal of the treatment, since the blueprint for bone removal is clearly delineated.

Crown lengthening procedures

Nowadays, crown lengthening procedures have come to be accepted as an esthetics-driven form of periodontal surgery. In crown lengthening procedures, the clinician must address the biological width and consider the different biotypes in order to avoid potential postoperative complications (Ingber et al., 1977). The biological width can vary slightly from patient to patient and from anterior to posterior teeth (Gargiulo et al., 1961; Kois, 1994). Thus, the biological width, the periodontal health, and the stability of the gingival margin after crown lengthening are important when one is trying to achieve ideal esthetics. Whatever the treatment plan option, the key to esthetic success depends on the preservation of the buccal cortical plate and interproximal bone of the alveolar sockets, and on the symmetry of the gingival contour which frames the natural teeth.

It is important that the same quantity of bone be removed or retained in order to create normal biological parameters. Authentic esthetic dentistry is only possible if the periodontal space is in perfect condition (Lowe, 2009).

The biological objectives

Indications

Crown lengthening procedures are indicated to provide adequate tooth structure in cases of subgingival tooth fracture (Hu et al., 2008), subgingival caries (Hempton and Esrason, 2000), root resorption (Reddy, 2003), uneven gingival levels, unesthetic short crowns due to tooth wear, inadequate axial height for retention of restorations, altered passive eruption of a single or multiple teeth, and, finally, in cases of a gingival smile – called a “gummy smile” – with short natural crowns.

The objective of crown lengthening in restorative cases is to increase the axial length of the crown, and to strengthen the anchoring of the restored teeth, by surgically moving the alveolar crest bone to a more apical position, thereby providing adequate tooth structure to safely prepare the restoration. It also helps to reestablish the new physiological biological width.

The alveolar bone resection will depend on the type of the apical level of the restoration:

- If the restoration has a suprasulcular limit, the amount of bone resection should leave a minimum of 3.0–3.5 mm of sound tooth structure from the restoration margin (see Fig. 4.29b).

- If the restoration has an intrasulcular limit, the amount of bone resection should leave a minimum of 2.5–3.0 mm of sound tooth structure from the restoration margin (see Fig. 4.29c).

Figure 5.2 (a) Old anterior teeth preparation, violating the biological width, with irregular gingival contour. (b) The clinical aspect, with supragingival temporary crowns, 3 months after the bone has been surgically removed and the flap sutured more apically. (c) The final ceramometal anterior restorations after new subgingival preparation that respects the biological width 15 years later.

Subgingival preparation for esthetic restoration should not be initiated before a healthy sulcus is present (Figs 5.2a–c). This will take varying amounts of time, depending on the biotype (Rosenberg et al., 1980).

In nonrestorative cases, crown lengthening is an independent procedure and is mainly performed to enhance esthetics. Excessively short teeth, lack of tooth display, and excessive gingival display require clinical crown lengthening, which can present a clinical dilemma for the esthetic-oriented periodontist.

The overall treatment of the gingival smile is multidisciplinary, leading to teamwork focused on the various elements that make up the smile, and most particularly on the position of the upper lip line (Miskinyar, 1983).

There is a specific treatment corresponding to each etiology, with which – in most cases – will be associated complex therapy, peripheral complementary treatments, or gingivoplasty, with or without restorative treatment (Toca et al., 2008).

According to Goubron et al. (2011) the objective of the treatment should be to:

- Reestablish an ideal and symmetrical gingival margin.

- Obtain correct dimensions for the tooth crown.

- Harmonize the smile from the first and second premolars on the right side to the first and second premolars on the left side.

- Maintain a long-term result with the optimal biological width, and that has a distance of 3 mm from the new gingival margin to the reshaped (osteoectomy–osteoplasty) crestal bone.

The architecture of the gingival margin should follow the alveolar bone margin that is found 3 mm below the cervical limit of the restoration. The alveolar bone contour should resemble the margin of the restoration, but displaced 3 mm apically to respect, and allow for the reformation of, the normal biological width and sulcus (Lowe, 2004).

Any esthetic modification should take into consideration perfect knowledge of the position of the teeth and of the desired symmetry of the gingival profiles.

The rationale

The need to establish the correct tooth size and the proportions of the individual teeth drives the periodontal component of esthetic restorative dentistry (Chu, 2007).

Midfacial surgical crown lengthening has traditionally been performed to establish a healthy biological dimension of the dentogingival complex as an adjunct to esthetic restorative procedures. This procedure involves a multifaceted decision-making process, with the endpoint being whether or not hard and/or soft tissues can be excised and/or should be repositioned. Therefore, it is important to determine the position of the underlying bone in relation to the gingival tissue.

In order to obtain desirable final results in the esthetic region, preservation of the interproximal papillae is essential (Nemcovsky et al., 2001). Several authors have suggested that 3 mm of supracrestal tooth structure be established during surgical crown lengthening (Kois, 2006).

It is important to establish a consistent measurement that is representative of the dentogingival complex dimension, which is critical for health and for restorative success when performing surgical crown lengthening. Patients who exhibit asymmetrical gingival levels, and those with greater than 3–5 mm of maxillary gingival display, or both, may be candidates for surgical gingival and/or alveolar bone repositioning to improve their esthetics. Typically, these patient types have adequate amounts of attached gingiva to prevent the mucogingival junction from being encroached upon after the resective procedure. If an adequate amount of free gingiva exists, minor asymmetries can be corrected by means of internal gingivectomy or gingivoplasty alone. A minimum sulcus depth of 1 mm must always remain after any tissue resection, unless alveolar bone crest is repositioned in the apical direction as well.

Current crown lengthening procedures

The treatment modality for esthetic crown lengthening should be based on detailed diagnosis in each case, because the type of therapy selected by the clinician will have direct implications for the esthetics (Kao et al., 2008). Like the gingival margin and the bone level, the periodontal biotype can vary after crown lengthening surgery, depending on the patient’s osseous biotype (Pontoriero and Carnevale, 2001).

Depending on the clinical situation regarding the amount of keratinized gingiva in the gingival margins, with or without disharmony in relation to the alveolar crest to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ), there are two main clinical protocols for the treatment of these gingival anomalies:

- This is used without flap elevation and with a marginal incision to create, at a new level, a harmonious gingival margin contour without osseous resection, when there is an excess of gingival tissue (> 3–5 mm, Type I-A) with a correct marginal bone crest relation with the cemento-enamel junction (> 1.5–2.0 mm) (Figs 5.3a–v).

- It is used with flap elevation, with a sulcular incision and osseous resection, when there is inadequate gingival tissue (≤ 3 mm, Type II-A) with a correct marginal bone crest relation with the cemento-enamel junction (>1.5–2.0 mm) (Figs 5.4a–f).

- Adequate gingival tissue (>3–5 mm, Type I-B), with an inadequate marginal bone crest relation with the cemento-enamel junction (<1 mm). A marginal incision is recommended, with an apically repositioned flap (Figs 5.5a–f).

- Inadequate gingival tissue (≤ 3 mm, Type II-B), with an inadequate marginal bone crest relation with the cemento-enamel junction (< 1 mm) and/or gingival disharmony. A sulcular incision is recommended, with an apically repositioned flap (Figs 5.5g–k).

- Crown lengthening could be also combined with implant therapy, carried out during the same surgical session, to achieve a better planned and more esthetic result (Figs 5.5l–q).

- Forced eruption is the most common procedure for restoring an isolated tooth in order to prevent gingival disharmony with the adjacent teeth after the procedure (Figs 5.6a–c). If the bone is located below the mucogingival line, the amount of keratinized gingiva and bone will increase without changing the level of the mucogingival junction. On the other hand, if the mucogingival junction is below the bone crest, the amount of keratinized gingiva will remain constant, followed by a coronal movement of the mucogingival junction, but the bone will still move coronally (Chu and Hochman, 2011).

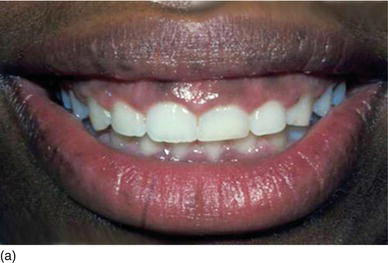

Figure 5.3 (a) A top model’s gingival smile, with short crowns and an absence of make-up, to avoid drawing attention to herself. (b) A frontal view of the gingival smile, with pigmented attached gingiva. (c) The intrabuccal right profile, showing excessive amounts of KG. (d) The left profile, also showing a large band of KG (Type I-A). (e) An internal beveled supracrestal incision involving the tip of the papillae on the anterior teeth combined with a sulcular incision; the gingival margin is then removed. (f) Continuous silk sutures after surgery on the maxillary and mandibular teeth, leaving 3 mm of gingival tissue from the bone crest.

Figure 5.3 (g) After a scalloped internal bevel incision has been extended around all of the right maxillary and mandibulary teeth, the gingival margin is removed and continuous silk sutures are put into place. (h) After a scalloped internal bevel incision has been extended around all of the left maxillary and mandibulary teeth, with double contour incisions on molars, continuous silk sutures are put into place. (i) Her new confident and enthusiastic smile, now enhanced by make-up. (j) The frontal view of the patient’ new smile, showing longer teeth. (k) The right profile aspect of an excessive gingival display (Type I-A). (l) The left profile with excessive gingiva, more pronounced than on the right lateral.

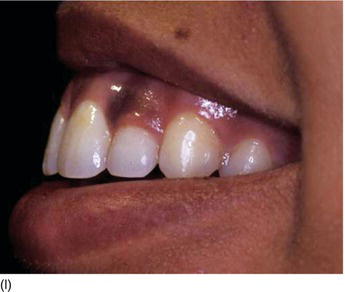

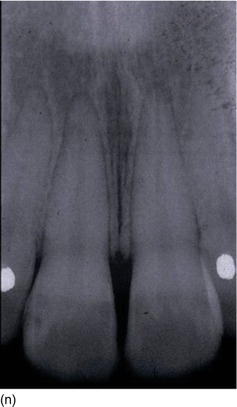

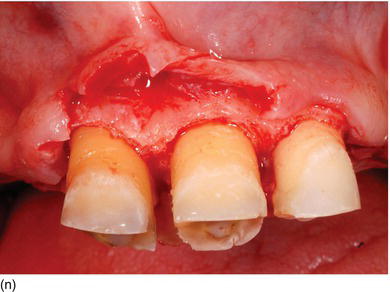

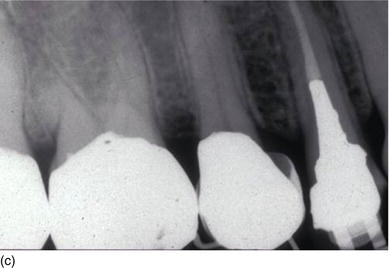

Figure 5.3 (m) The frontal view, showing the excess of gingiva with gingival disharmony. (n) A semilunar marginal internal incision not involving the tip of the papilla. (p) The same type of incision as on the right side, with a higher incision on the lateral. (o) An X-ray of the central incisors, revealing the absence of a contact point and a correct interproximal bone level. (q) Checking the level of the gingival margin on the right anterior teeth. (r) The clinical aspect at the end of the surgical session.

Figure 5.3 (s) The clinical aspect 2 weeks after surgery. (t) The 6-month postoperative result on the right profile of the smile. (u) The patient now feels good about herself and uses make-up. (v) A gingival display of < 1 mm on the left profile, in harmony with the lip contour.

Figure 5.4 (a) A smile before surgery, with dentogingival and lower lip disharmony. (b) Short clinical crowns and an irregular gingival margin level on the right side (Type II-A). (c) Full thickness flap elevation, with harmonious apical bone resection. (d) Three months postoperative healing after an apically repositioned flap. (e) Laminate ceramic veneers from cuspid to cuspid with gingival harmony. (f) A beautiful smile, with the three components – the lips, teeth and gingiva – in harmony. (Courtesy of Dr. M. Okawa, Tokyo, Japan.)

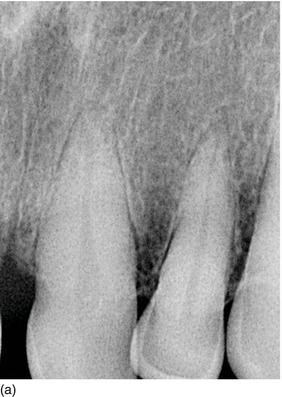

Figure 5.5 (a) X-rays of the right anterior teeth, with the interproximal bone level at the CEJ. (b) The patient’s occlusal deep bite, with an excessive amount of KG (Type I-B). (c) After orthodontic treatment was completed, full-mouth flap elevation was performed after marginal incision, with the bone crest at the CEJ level. (d) Buccal osseous resection to restore the biological space between the CEJ and the BC. (e) An apically repositioned flap, showing longer teeth. (f) The full-mouth ceramic restoration, with a normal occlusal relation (Restoration Dr. Raygot C, Paris, France).

Figure 5.5 (g) The anterior lower teeth, with delayed passive eruption and abrasion (Type II-B). (h) After full-thickness flap elevation, the bone almost reaches the CEJ level. (i) The bone is resected apically and harmoniously 2 mm below the CEJ. (j) The sutures will be removed 1 week after the surgery. (k) Laminate veneer restorations on the eight lower anterior teeth (restorations by Dr. S. Koubi, Marseille, France).

Figure 5.5 (l) Abrasion of the anterior teeth, with collapse of the posterior bite. (m) The bone crest level close to the CEJ. (n) Crestal bone resection to establish a minimum of 3–4 mm from the CEJ level and improve the structure of the teeth for preparation of the restoration. (o) The occlusal aspect of the ridge after implant osseointegration and soft tissue maturation. (p) The same occlusal aspect with the implant abutments. (q) The full mouth fixed and with rigid dento-implant restoration. (Courtesy of Dr. A. Peivandi, Lyon, France.)

Figure 5.6 (a) Forced eruption performed before crown lengthening. (b) During the process of forced eruption, the KG increased in height in comparison to the adjacent teeth and the bone moved down. (c) The excess of bone was resected only on the premolar, keeping the correct bone level on the adjacent teeth.

The two surgical approaches, more or less invasive, involving gingival resection with osseous resection are the closed flap technique and the open flap technique, as follows.

The closed flap technique on Type I-A

This technique can be used in lieu of a flap elevation procedure to make the correction and complete the restorative process without the healing time required for open flap crown lengthening surgery (Figs 5.7a–j). Pati/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses