Disease Transmission

Learning Objectives

1 Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

2 Compare bacteria and viruses and give examples of each.

3 Discuss the causes of bacterial endocarditis.

4 Explain the differences between acute, chronic, latent, and opportunistic infections.

5 Identify the modes of disease transmission in a dental office.

6 Explain the concept of the chain of infection.

7 Name five ways in which disease transmission can occur in the dental setting.

8 Name the bloodborne diseases that are of major concern to dental healthcare professionals.

9 Describe the portals of entry for disease transmission in a dental office.

10 Identify the diseases of concern to dental healthcare workers.

11 Explain the precautions necessary when treating a patient with active tuberculosis.

Key Terms

Acute Infection

Aerosols

Bacteria

Bacterial Endocarditis

Bloodborne Diseases

Chronic Infections

Cross-contamination

Direct Transmission

Fungi

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis D

HIV

Host

Host Resistance

Indirect Transmission

Infectious Diseases

Latent Infection

Mists

Opportunistic Infections

Parenteral Transmission

Pathogen

Portal of Entry

Spores

Tuberculosis

Virulence

Viruses

The dental assistant is at risk of exposure to infectious diseases through occupational exposure. In this chapter, you will learn about the organisms that cause infectious diseases and will learn to recognize the diseases that are of particular concern to dental professionals. You will learn how these diseases can be spread within the dental office and the steps you can take to protect yourself, other staff members, and patients from disease transmission in the dental office.

Pathogens

A pathogen is a microorganism that is capable of causing disease. These microorganisms are so small that they can be seen only with a microscope.

Bacteria

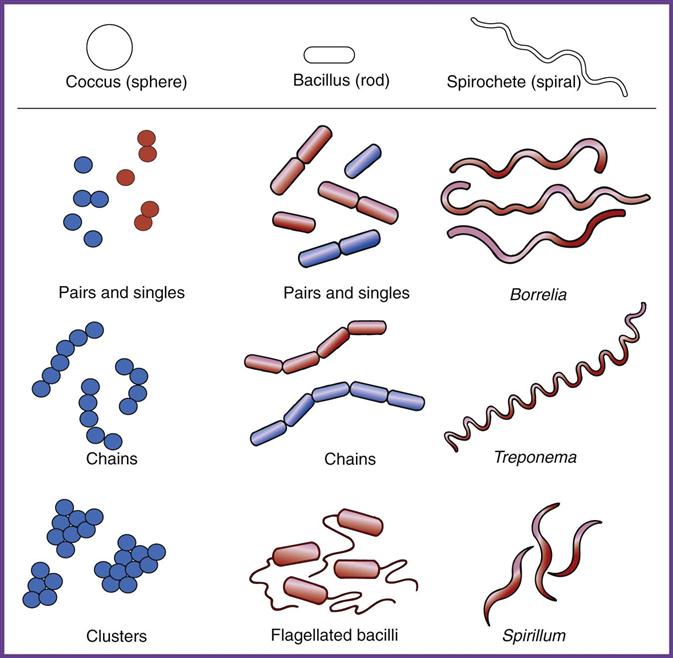

Bacteria (singular bacterium) are a large group of one-celled microorganisms that vary in size, shape, and arrangement of cells. Most bacteria are capable of living independently under favorable environmental conditions. Pathogenic bacteria usually grow best at 98.6° F (37° C) in a moist, dark environment.

A bacterial infection can be spread by many means of transmission. Humans host a variety of bacteria at all times. The skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract are inhabited by a great variety of harmless bacteria, called normal flora. They are beneficial and protect the human host by aiding in metabolism and preventing entrance of harmful bacteria. An infection occurs when bacteria occurring naturally in one part of the body invade another part of the body and become harmful. Most bacterial infections are treated with antibiotics.

When viewed under a microscope, bacteria have three shapes: spherical, rod-shaped, and spiral (Figure 5-1 and Table 5-1).

TABLE 5-1

Shapes of Bacteria and Diseases in Which They Occur

| Shape | Name | Disease |

| Spherical | Streptococci | “Strep” throat, pneumonia, tonsillitis |

| Staphylococci | Boils, skin infections, pneumonia | |

| Rod-shaped | Bacilli | Tuberculosis |

| Spiral-shaped | Spirochetes | Syphilis, Lyme disease |

Spores

Under unfavorable conditions, some bacteria change into a highly resistant form called spores. Tetanus is an example of a disease caused by a spore-forming bacillus.

Bacteria remain alive in the spore form, but are inactive. In the spore state, they cannot reproduce or cause disease. When conditions are again favorable, the bacteria become active and capable of causing disease.

Spores represent the most resistant form of life known. They can survive extremes of heat and dryness and even the presence of disinfectants and radiation. Because of this incredible resistance, harmless spores are used to test the effectiveness of techniques used to sterilize dental instruments (see Chapter 8).

Viruses

Viruses are much smaller than bacteria. Despite their tiny size, many viruses cause fatal diseases. New and increasingly destructive viruses are being discovered and have resulted in the creation of a special area within microbiology called virology (the study of viruses and their effects).

Viruses can live and multiply only inside an appropriate host cell. Host cells may be human, animal, plant, or bacteria.

A virus invades a host cell, replicates (produces copies of itself), and then destroys the host cell so the viruses are released into the body. The various forms of viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

Latency

Some viruses establish a latent (dormant) state in host cells. A latent virus can be reactivated in the future and can produce more infective viral particles, followed by signs and symptoms of the disease.

Stress, infection with another virus, and exposure to ultraviolet light can reactivate the virus. Some HIV patients have experienced prolonged periods of latency and have remained in good health for many years. For example, hepatitis C is known to have a latency period of 15 to 25 years.

Treatment of Viral Diseases

Viruses cause many clinically significant diseases in humans. Unfortunately, most viral diseases can be treated only symptomatically, that is, by treating the symptom, not the infective cause.

General antibiotics are ineffective in preventing or curtailing viral infections. Even the few drugs that are effective against specific viruses have limitations because viruses often produce different types of infection, have different host cells, or can cause serious side effects.

Viruses are also capable of mutation (changing). Viruses can change so they are better suited to survive current conditions and resist efforts to kill them. It is very difficult to develop vaccines against viruses because of their ability to change their genetic code.

Fungi

Fungi are plants such as mushrooms, yeasts, and molds that lack chlorophyll. (Chlorophyll is the substance that makes plants green.) Athlete’s foot, ringworm (which is not a worm), and candidiasis are examples of diseases caused by fungi.

Oral candidiasis is caused by the yeast Candida albicans. All forms of candidiasis are considered to be opportunistic infections, especially affecting very young, very old, and very ill patients. Infants and terminally ill patients are also at risk. Candidiasis is common under dentures in patients with HIV infection.

Oral candidiasis is characterized by white membranes on the surface of the oral mucosa, on the tongue, and elsewhere in the oral cavity. The lesions may resemble thin cottage cheese; wiping reveals a raw, red, and sometimes bleeding base (Figure 5-2). Candidiasis is treated with topical antifungal preparations such as nystatin in the form of lozenges.

Disease Transmission

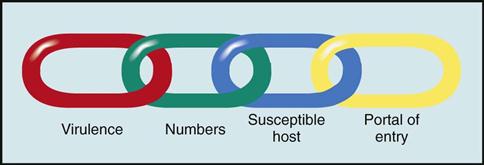

The potential for disease transmission is always present when pathogens find an ideal place to live and grow. Four factors influence the disease-producing capability of a pathogenic organism. Imagine these factors as links in a chain of infection. If one of these links is broken, disease transmission cannot occur (Figure 5-3):

Host resistance is the ability of the human body (the host) to resist a pathogen. The healthier you are, the better your resistance to disease. Lower resistance can result from fatigue, physical or emotional strain, poor nutrition, injury, surgery, or the presence of other diseases.

Virulence, which is also known as infectivity, describes the ability of the pathogen to overcome the individual’s body defenses and cause disease. A highly virulent pathogen is able to overcome the host’s defenses, even in healthy individuals who are able to resist other diseases.

Concentration refers to the number of pathogens that are present. The more pathogens that are present, the better their chances of overwhelming the host and producing disease.

Portal of entry refers to the method by which the pathogen enters the body. The portals of entry for airborne pathogens are through the mouth and nose. Bloodborne pathogens must have access to the blood supply as a means of entry into the body. This can occur through a break in the skin caused by a needle stick, a cut, or even a human bite. It can also occur through the mucous membranes of the nose and oral cavity (Table 5-2).

TABLE 5-2

Portals of Entry for Disease Transmission

| Portal | Examples | Means of Prevention |

| Inhalation | Breathing aerosols generated from handpieces or the air-water syringe, or from uncovered ultrasonic cleaning devices | Wear face masks during chairside procedures and when processing contaminated instruments and surfaces |

| Ingestion | Swallowing droplets of blood or saliva spattered into the mouth; bare hands come into contact with contaminated surfaces or items and the hands then handle food items | Wear face masks, wash hands frequently, keep surfaces free from contamination by using barriers or surface disinfectants |

| Mucous membranes | Droplets of blood or saliva spattered into eyes, nose, or mouth | Wear face masks and safety glasses with side and bottom shields during chairside procedures and when processing contaminated instruments and surfaces |

Infection control efforts are aimed at preventing the transmission of disease and reducing the number of pathogens that are present (Box 5-1).

Types of Infections

An infection occurs when a pathogenic microbe is able to multiply in the tissue in which it is lodged. An infectious disease is one that is communicable or contagious. These terms mean that the disease can be transmitted (spread) in some way from one host to another.

Acute Infection

In an acute infection, symptoms are often severe and usually appear soon after the initial infection occurs. Acute infections are of short duration. For example, with a viral infection, such as the common cold, the body’s defense mechanisms usually eliminate the virus within 2 to 3 weeks.

Chronic Infection

Chronic infections are those in which the microorganism is present for a long duration; some may persist for life. The person may be asymptomatic (not showing symptoms of the disease), but may still be a carrier of the disease, as with hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), or HIV infection.

Latent Infection

A latent infection is a persistent infection in which the symptoms “come and go.” Cold sores (oral herpes simplex) and genital herpes are latent viral infections.

The virus first enters the body and causes the original lesion. It then lies dormant away from the surface in a nerve cell until certain conditions (such as illness with fever, sunburn, and stress) cause the virus to leave the nerve cell and seek the surface again. Once the virus reaches the surface, it becomes detectable for a short time and causes another outbreak at that site.

Opportunistic Infection

Opportunistic infections are caused by normally nonpathogenic organisms and occur in individuals whose resistance is decreased or compromised. For example, an individual recovering from influenza may develop pneumonia or an ear infection. Opportunistic infections are common in patients with autoimmune disease or diabetes and in elderly persons.

Modes of Disease Transmission

Before you can prevent disease transmission in the dental office, you must first understand how infectious diseases are spread (Figure 5-4 and Table 5-3).

TABLE 5-3

Modes of Disease Transmission in the Dental Office

| Mode | Description |

| Direct | Contact with infectious lesions or infected blood and/or saliva |

| Indirect | Contact with a contaminated object, such as instruments, surfaces, or dental equipment |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses