4

Chairside management of the fearful dental patient: behavioral modalities and methods

In the preceding chapters, we have discussed the basic concepts associated with phobias and emotions of anxiety and fear. We have also mentioned the various common determinants associated with creating fearful dental patients and their chairside implications as determined by the findings of numerous dental and nondental clinical studies. The previous chapters discussed numerous factors that affect the assessment, collection of information, and identification of the dentally fearful individual, as well as chairside implications and considerations that can affect the success or failure of treatment.

In this chapter, I would like to present both a model that brings together findings from past studies and personal experiences, and a cohesive chairside program that follows from that model, for the behavior management and lessening of fear of dental treatment before, during and after the office visit. Using this model and clinical program, dental practitioners should be able easily to formulate and adapt a similar successful chairside model program suitable to their unique needs and practice styles. By utilizing this information and combining it with their own personal experiences, they can construct, as I have done, a successful chairside approach that lessens, and makes manageable, dental fears found in the clinical practices of dentistry.

THE CONCEPT OF THE DENTAL PRACTITIONER A S A “FACILITATOR OF CHANGE”

One of the first changes I recognized that had to take place before I would see any successful modification of a patient’s behavior was that I would first need change my own behavior and approach to both the anxious, fearful person as well as the nonfearful ones. As dental practitioners, we do make changes automatically to accommodate every patient problem, and every patient complaint, whether confronted with it in our office, or when we try to convince patients to improve their home care. We become empathetic, bending in our verbal and nonverbal behavior to make them comfortable and at ease. We modify a technique to make it appear less fearful. Most of the time, we make these changes quite naturally, fitting our responses to meet the demands of the situation better, and sometimes we do this without even realizing that we have, in fact, changed a portion of our routine.

Conversely, patients often do the same to us when they attempt to:

- control their treatment;

- lessen a fee;

- insist upon a certain type of restoration; or

- change an appointment date.

Dworkin1–3 mentions that one of the basic clichés of any change in behavior or attitude involving an interpersonal relationship between two or more individuals is that when the behavior of one individual within a relationship changes, that change compels others in that relationship to change too. If dental practitioners wish to change the behavior of patients to more positive and well-meaning goals, then it is self-evident that clinicians must first consider examining and modifying their own behavior, and do the same when required. When dental practitioners change their behavior to meet the needs of others in the dentist–patient interpersonal relationship, they demonstrate an understanding that such behavior change is a reciprocal process. When this reciprocal process works well, each individual has changed to behaviors that are both personally and interpersonally acceptable and positive. It is important to remember that when individuals seek dental care, they are in reality seeking a change, a change in their oral health and their well being. The rewards for making these behavioral changes include having a more compliant, appreciative and long-lasting patient relationship, as well as a much easier work environment. The patient becomes more enjoyable, and the dental practitioner feels not only more relaxed, but more satisfied as a healing health professional.

This change on the part of the patient may involve a wish for a different treatment plan or a change in treatment behaviors and attitudes from a past practitioner. There are a number of factors that the dental practitioner can focus upon that influence a patient’s behavior, such as:

- physical and psychosocial environment;

- individual patient /dentist’s perceptions;

- vicarious patient learning habits; and

- past negative and positive patient experiences.

Thus, the concept of change needs to be understood as it relates to:

- change that concerns the dentist as an agent of change;

- change that concerns the dental patient.

Change associated with the dental practitioner

It cannot be stressed enough that in order for the dental practitioner to be able to cause a patient to understand, be motivated, accept, appreciate, and continue treatment without negative and disruptive behavior, the practitioner must be able to create changes that favor a positive patient relationship. The interaction and relationship that exist between patient and dentist is a mix of psychological/emotional variables including:

- fear;

- self-esteem;

- variations in personalities,

- environment, and

- parental and cultural influences.

These patient factors are also found to some extent within the practitioner, who inevitably has self-esteem needs, as well as personality traits that were either learned or perhaps inborn. Ideally, these practitioner characteristics are largely positive and can be used to good advantage by the dentist as a change agent. But in any case, the practitioner as a person is an equal contributor to that complex interaction we call “the dentist–patient relationship.” When these factors collide with each other and the relationship that ensues is not positively shaped, such a relationship can shift from friendship to anger and frustration. Behaviors that negatively affect and shape the patient–dentist relationship need to be minimized by effecting a change that creates a positive flavor to the dentist–patient interaction.

Chairside clinical implications of change

The occurrence of positive changes in the dentist–patient interaction permits the practitioner to maximize his or her ability:

- to efficiently gather and provide information;

- to determine and discuss reasons for past inappropriate dental behavior, and develop a positive change strategy for specific individuals; and

- to develop trust and rapport more easily, leading to treatment compliance and patient satisfaction.

The dental practitioner must deal on a daily basis with a variety of inappropriate behaviors and conflicts—having typically received little to no education in how to understand or manage them. Too often, these psychological, emotional, cultural, and economic concerns result in behaviors that lead to uncompleted treatment. That these aversive behaviors present frequent difficulties, which interfere with treatment, is reason enough for dental practitioners to want to take suitable actions to create an environment that permits only positive behavior while minimizing the negative ones. The practitioner must develop an increased willingness to listen, along with an increased sensitivity that causes them to become totally aware of what the patient perceives his or her needs and goals to be. This must include an increased effort and determination to gain an understanding and perception of the cause of a patient’s negative actions, along with conduct on the part of the dentist that demonstrates the practitioner perceives these behaviors as problematic and is willing to help the patient cope with them. Practitioners must constantly engage their patients and learn to use a variety of behavioral strategies that minimize conditions the patient perceives to be negative and maximize those the patient perceives to be positive.

A facilitator of change

The dental practitioner must act as a “facilitator of change” and implement change whenever the dentist–patient interaction is perceived to be either becoming uncomfortable or interfering in the optimal provision of care. In this situation, it is the dentist who must be the first in the relationship to institute change, permitting the patient’s behavior change to be the result of the practitioner’s new behavior.

For me, the way to attain these goals successfully, and to be able to change when circumstances within the ongoing interaction demand, has been through the use of:

- pretreatment, as well as mid-and posttreatment questionnaires;

- a well-developed set of listening and communication skills;

- a clear set of behavioral change or behavior modification strategies; and

- a readiness to change my routine behavior to behavior that meets the needs and goals of the patient without sacrificing any of my own objective and subjective needs and goals.

The information collected from a compilation of items studied on prior on questionnaires 4–20 and presented to patients in the form of self-report questionnaires, provides me with the information necessary, to gain an insight into needs, goals, and make-up of the individuals seeking care. It permits me to be pre-prepared to change from my professionally trained method of providing care to an approach that initially will not appear threatening and in conflict with the needs and care the patient perceives he or she requires.

For example, this is a situation I am sure many practitioners have encountered, the patient who does not wish to have local anesthesia. Dentists, however, routinely works with such anesthesia for the comfort of the patient and the ease of providing pain-free dentistry to their patients. I often used the following example to my students when discussing the need for the practitioner to institute a change in behavior in order to accomplish a desired end result, in this case, the restoration of a large carious lesion.

A young man had presented to our office for the restoration of several large carious lesions. The information collected from our pretreatment questionnaires and initial office consultation provided little information concerning any fear of dental treatment, either past or present. There was no apparent fear of needles, no past negative experience with previous care, and a medical and dental history that was essentially uneventful. The patient stated that after his discharge from active duty and a lengthy period of unemployment, his oral care had slipped.

After completing the required periodontal prophylaxis, we suggested to him that we begin by treating the largest of the decayed teeth first. The patient informed me that he was a former Green Beret and that he could withstand a great deal of pain, and that he preferred no regional anesthetic. He stated he had endured far worse discomfort on the battlefield than that caused by drilling a tooth. I agreed to begin without a local anesthetic even though I doubted he could endure the discomfort that was to follow.

By proceeding in this manner, that is, agreeing to accept the patient’s self-perceived lack of need of anesthesia, I have immediately demonstrated:

- That by offering to change my normal operating behavior, I am permitting the patient to realize that his current need for no anesthesia, has been recognized by me and that it supersedes my need to use Novocain routinely.

- That I am an individual who is sensitive to his motivations and perceptual needs, and is willing to proceed initially in a manner less threatening to his well-being.

In doing so, I am confirming a willingness to adapt to his needs immediately rather than trying to figure out what other motives are behind his refusal to want anesthesia. However, although I am willing to change my behavior, I expect that the patient will have a mutual and reciprocal willingness to modify his behavior, should circumstances arise that interfere with my ability to provide excellent dentistry. If my change of behavior is to act as a vehicle and initiate a reciprocal positive change in his behavior, when required, a mutual understanding has to be reached: that should during the preparation of the tooth the drill causes undue discomfort and result in frequent interfering movements, the patient must be willing to change and permit me:

- to demonstrate that I can provide a relatively pain-free injection; and

- to complete the dental treatment in a comfortable and pain-free manner thanks to the use of anesthesia.

Chairside clinical consideration

To be able to facilitate a change in a patient’s behavior, the dentist must consistently:

- Recognize when the patient or the practitioner perceives that a problem exists.

- Discuss the existence of the problem, and validate the patient’s perception that a problem exists.

- Implement an appropriate strategy to alleviate the immediate difficulty.

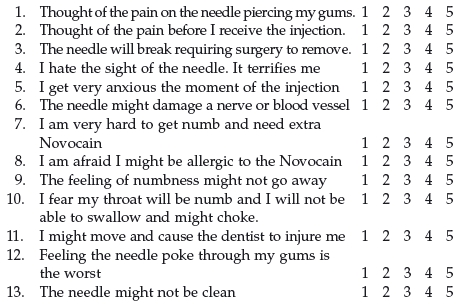

If in this case, the patient still refuses to receive anesthesia, and I believe that without it an inability exists on my part to restore the tooth properly, I do not immediately institute treatment without attempting to learn the reasons for the patient’s refusal. Highly anxious patients often report more pain during dental injections.21–29 I find it imperative to know exactly why the patient refuses the dental injection by posing the following questions on a scale of Likert scale 1–5.

This series of questions is posed during the initial consult with the patient, and as the responses are elicited, I discuss each one, attempting to find out what if any past experiences or vicariously learned negative cognitions are influencing the responses. We also attempt to inform patients about newer techniques now available, if I determine that their present thoughts are influenced by past out-of-date experiences and knowledge. If necessary, I will devote additional time to demonstrating my technique using topical anesthetic, and if that is insufficient, I will add the nitrous oxide-oxygen conscious-analgesia concept, the objective being to demonstrate that dental anesthesia administration can be pain free and permit discomfort-free dentistry to occur. I also like to remind the patient that drilling can excessively overstimulate the nerve tissue fibers and that local anesthesia not only prevents pain now, but also keeps the tooth healthier and pain free in the future.

This questionnaire is hand held by the patient as we address and discuss each item on the sheet.

Situations Associated with My Fear of the Dental Injection

1. not at all, 2. very slightly 3. Moderately fearful, 4. severely fearful 5. Avoid completely

I am bothered

If after going over the entire questionnaire I cannot change the patient’s behavior, I then suggest that a referral might be needed to seek any hidden emotional or psychological disorders influencing the patient’s decision in this matter.

Change associated with the dental patient

The process of helping the patient change begins, obviously, with the practitioner ascertaining what the patient’s perception of the problem is, and then providing assurance that the problem is one which is valid—and valid simply because the patient perceives it to be so. It is not necessary most of the time for the practitioner to know the exact and true cause of the fear. The real objective of the dentist in facilitating a change is to identify and manipulate whatever factors exist in the psychosocial–physiological environment that are presently fearful to the patient, so as to be able to deliver the desired optimal dental care today and understand what will be required tomorrow.

Three chairside clinical objectives

- Determine the needs, goals and motivations of patient.

- Assess the existing relationship between the dentist and patient, i.e., the degree of trust and rapport that exist, in an effort to determine the best behavioral modality to utilize so as to achieve the best behavioral results.

- Relate to the patient in terms and wordings that are designed to minimize circumstances the patient perceives as negative and threatening, and to maximize those conditions the patient perceives to be positive and not threatening or fear provoking.*

In my practice, to accomplish the first of these three objectives—determining needs, goals and relevant past experience—we utilized questionnaires such as those found on Chapter 2.

First, and most important, is the determination of needs and goals of the individual. These factors directly influence the patient’s behavior, with a resulting impact on the practitioner’s ability to affect change. For the dental practitioner it is necessary to:

(1) Understand the patients’ needs, the why s and where they arise from.

(2) Acknowledge those needs and communicate to the patient our understanding of them and our desire to help them achieve and fulfill those needs and goals.

(3) Convey the message as dentists, both verbally and nonverbally, of our intentions and objectives in a manner that is persuasive but not overbearing so as to influence and change their behavior to positive and acceptable modes.

In the preceding chapters, we have emphasized the many emotional, anxious/fearful factors, and feelings associated with past dental care or avoidance of care. These following factors are also equally important considerations in the second objective in producing change: assessing the dentist–patient relationship and the ability for the practitioner to facilitate change. The practitioner should ascertain

- What is this patient’s overall attitude toward dentistry in general?

- Why, if a new patient, has the individual chosen you as his or her new dentist?

- What, if any, are the patient’s negative past experiences, and how have they shaped his or her present fears, attitudes, and emotions?

- What are the patient’s individual personality traits, age, education level, occupation, and past dental history?

- What degree of positive influence, if any, already exists over this patient? Those referred to you by a former patient may already have a certain level of trust in you, facilitating a greater willingness on the part of the patient to accept help offered by the practitioner in coping with such patients perceive to be their problem.

- What are your behavior management and treatment objectives regarding this patient, and how do you intend to achieve them? What are your long term goals?

- What strategy will best suit this individual? How and when will you present this change strategy? Can you reason with this individual? Does the patient have the ability to understand the need and importance of the intended treatment?

The third objective affecting the patient’s change is determining what behavioral strategy a practitioner decides to implement. The dental practitioner, in making this decision, must understand and deal with all of the factors that play a role in the patient’s behavior. The practitioner, in attempting to change a patient’s behavior, must be confident that his or her messages are heard, understood, and accepted as truth by the patient. The message, whether it be a strategy to overcome fear and anxiety or the presentation of a treatment plan, should be presented in an orderly and logical sequence in a manner that will positively influence the behavior of a specific patient.

To construct and influence strategies that will have positive effects on a patient, one must constantly assess a patient’s physical and psychological state of well-being. A periodic review and update of a patient’s history, as well as the degree of positive progress an implemented strategy has provided, will allow the practitioner to identify potential sources of influence clearly as they develop. Constant monitoring of behavioral progress using mid treatment questionnaires also helps eliminate any minor existing negative influences still being perceived by the patient as a problem. I realize that all these tasks must seem monumental and requiring time that may not immediately appear to be rewarding financially. But I can emphatically state that if you are looking to reduce stress, lessen negative behavior, increase patient satisfaction, lessen cancelled and broken appointments, add this modality of “behavior change” to your treatment armamentarium and watch treatment compliance increase.

This concept that I advocate is not a difficult one; in reality, it is quite simple. The issue from where I see it is not that it is difficult to get patients to change away from their negative, aversive and fearful behavior, because it is not; the difficulty is trying to get the dental practitioner to change from only paying attention to the things needed to fix the patient’s dentition. Two elements must change if a practitioner wishes to improve his management skills in treating the fearful patient, and they are the patient and the dentist. I try to attach a change in behavior to a patient’s importance and value they may place on treatment previously rendered or presently needed.

For example:

- For the patient who has recently completed extensive periodontal treatment, I would suggest:

The reason you undertook such intensive and expensive treatment was to improve your oral health, lessen your embarrassing bad breath, and improve your smile and well being. In the past, the cause for your periodontal disease was your lack of brushing, flossing and regular check-ups. Studies have shown that patients who maintain regular dental visits, and exhibit good home care habits, demonstrate fewer reoccurrences of previous periodontal disease and loss of teeth. I believe, that after all you have gone through, this has to motivate you to change your past neglectful behavior. You would not want to go through all that time and expense again, would you?

- A similar approach can be used to motivate the patient who has extensive caries involvement in their dentition, due to neglect and avoidance. To motivate this type of patient, I often search the past dental history, looking for some factor or occurrence that the patient has emphasized as hoping never to experience. A good example is the patient whose history demonstrates parents who wear dentures and who constantly has to listens to them complain about their difficulty with eating or speaking, or with dentures falling out when the wearer is talking. To such patients’ complaining how they hate to always see that or worrying that the same fate could befall him or her, I express empathy and attempt to initiate a change in behavior by trying to use their dislike of their parents’ situation, and to encourage these patients that by restoring their own badly decayed teeth, they prevent a similar repetition of their parents’ problems happening to them.

Remember that it is the dentist who must change first, because it is the dentist who is the vehicle of change for the patient’s change. It is the key to behavioral management success.

However, the dentist as a change agent does not seek to change the patient, per se, but only to change some of the patient’s behaviors and negative emotions, like anxiety, when they arise in the dental office.

STEP-BY-STEP CHAIRSIDE MODEL FOR FEAR AMELIORATION IN THE FRIGHTENED DENTAL PATIENT

Part 1: The office model

The first management technique begins with the first contact the patient has with our office, and that is with the receptionist. Our receptionist has been trained to ask a specific set of questions when a new patient calls for an initial appointment and to listen intently, paying attention to tone and content of the conversation. The receptionist must at all times be dignified, calm, empathetic, and understanding. After securing the patient’s name and phone number in case a disconnection occurs, the receptionist is instructed to ask specific questions regarding the following topics:

- Reason for appointment: The reason for the appointment—emergency or regular check-up. This allows us to determine the exact reason for the appointment.

- Any special concerns, fear, anxieties over treatment, past and present?: This question ideally will inform us of any fears or concerns about specific treatment, dentist’s attitudes, past experiences, or negative thoughts and cognitions. The tone of the patient’s expressions are noted, angry, calm, demanding, full of questions, or only statements of fear and concern about changing dentists. (Answers are noted.)

- Who referred you to this office?: It is important to know this for a couple of reasons: First is so as to be able to thank the individual responsible both for the referral and for having the sort of confidence in our ability to refer another person; second, to determine if individual was a prior frightened individual whom we successfully treated and lessened their fears. If so, it makes the referral even more meaningful. It indicates a past success. (Answers are listed.)

- Specific reason for changing dentist: What specific reasons are influencing changing dentist? This gives us the opportunity to learn past negative feelings or experiences a prior practitioner may have visited on the individual, which we prefer not to duplicate. We are also interested in any positive experiences the patient wishes to relate.

- How long ago was last dental visit?: How long has it been since the patient’s last regular visit to a dentist? It permits us to learn what issues have influenced the avoidance of care, what, if any, negative cognitions in the patient’s psychosocial sphere played a role in influencing the lack of care. (Answers are listed.)

- Specific physical needs, if any: Any special physical needs that the patient requires to ensure their comfort? This permits us to become aware if any special accommodations are required due to a physical handicap or medical disorder.

- The most convenient time for appointments: It is important to inquire whether a patient prefers a morning or afternoon appointment. Some individuals seem to function better during different times of the day, including coping better with fear or anxiety. Handicapped individuals and those with other medical conditions also have their own time of day that they function optimally.

During the initial phone contact, the receptionist can also begin the process of fear/anxiety reduction by informing the frightened patient that this dentist has a special interest in working with individuals who are apprehensive of dental treatment. Whatever the tone or reasons for requesting an appointment, the receptionist should always find a way to comment, “Well, you have come to the right office; Dr. Weiner is known for being very successful in treating fearful and anxious individuals. We have many, many wonderful patients who would gladly attest to that.” Remember, the first contact and the first opportunity to make a favorable impression starts with your receptionist and the initial phone call.

After I have consulted with my receptionist and reviewed both the patient’s responses to the questions and the receptionist’s impressions, notes are entered into the patient’s record concerning the overall impression of the initial contact. This extra time we take helps me to understand the patient’s needs and goals better, and serves as an opportunity to begin to establish trust and rapport. From this point, the patients are mailed a set of questionnaires as determined from their tone, content of information given and overall impression of the initial contact. These are described in Chapter 3, Figures 3.1–3.6. A stamped return envelope is included in the mailing. Usually, the initial appointment will be set up in a well-lit, comfortable area devoid off any equipment or relationship to dental care, and scheduled to permit adequate time for a complete and informative discussion.

Reception room phase of program

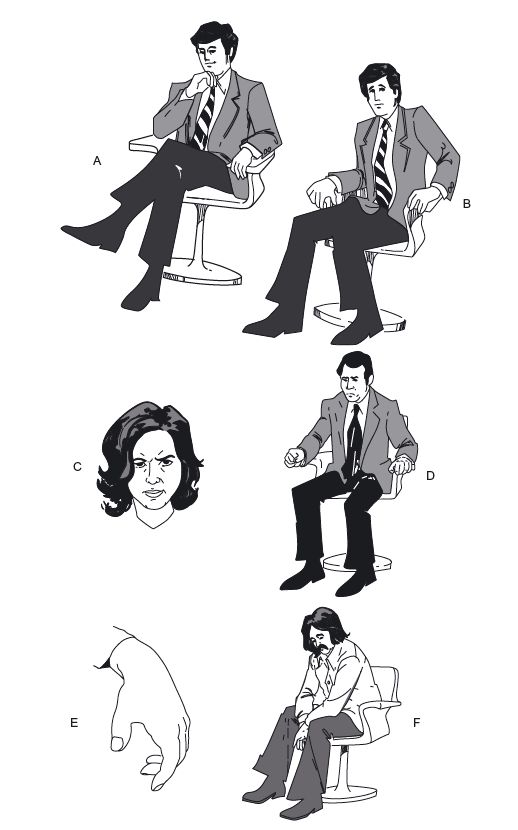

The behavior in the reception area can serve to provide and early indication of the emotional state of the patient, whether or not he or she is anxious, calm, etc. The individual best suited to monitor this behavior is the receptionist. We utilize a patient observation form that permits the receptionist to note the patient’s behavior; the receptionist is instructed, if uncomfortable or anxious behavior is noted, to meet and engage the patient in person (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Reception room monitoring. (A) relaxed, (B) sitting with white-knuckle grip, demonstrating possible anxiety or tendency to leave, (C and D) anger—frustration, (E and F) depression, feeling of hopelessness, “why me?”

Source: Dworkin S. 1978. Behavioral Science and Dental Practice. St. Louis. MO: CV Mosby. Used with permission.

Receptionist Patient Observation Assessment

0 – None at all, 1 – a little, 2 – Moderately, 3 – Severely

| Fidgeting with hands or object | _____ |

| Sitting on edge of chair or leaning forward | _____ |

| Pacing | _____ |

| Frequent changes in sitting position | _____ |

| Repetitious hand or leg movements | _____ |

| Frequent visits to rest room | _____ |

| Arrive on time? Yes___ No___ Never on time | _____ |

The dental practitioner can utilize the information relayed by the receptionist from his or her phone observations, and combine it with the information collected from the return of the previously mailed questionnaires to construct a specific plan for the approaching initial consult. The practitioner upon reviewing all the collected data can determine which areas need to be attended to and which areas in the sphere of dental care the patient does not perceive as presenting major concerns. All the bits of information received from the initial phone call and the returned questionnaires serve as pieces of the puzzle that when put together with the additional information gained during the consultation, guide us in determining what direction we need to proceed to lessen the individual’s fear. The questionnaires and consultation represent a compilation, a log book of the patient’s past fears, experiences, lik/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses