21 Periodontal Diseases

This chapter describes the epidemiology of gingivitis and adult periodontitis, their distribution, and the risk factors and background characteristics associated with them. Periodontal diseases have been prevalent throughout human history, although without the obvious secular variations that characterize dental caries. Human remains from the early Christian era show clear evidence of periodontal bone loss.156

PERIODONTAL INFECTIONS AND HOST RESPONSE

Both gingivitis and periodontitis result from bacterial infections. The expression of clinical disease, however, is a function of both bacterial infection and the host response to that infection, mediated by environmental factors like smoking and oral hygiene. Gingivitis is an inflammatory process of the gingiva in which the junctional epithelium, although altered by the disease, remains attached to the tooth at its original level. There are initial, early, and established gingivitis lesions, and a sequential microbial colonization leads to bacteriologically more complex plaque as the lesions progress.176

Periodontitis is also an inflammatory condition of the gingival tissues, characterized by clinical attachment loss (CAL) of the periodontal ligament and loss of bony support of the tooth. Periodontitis develops as an extension of gingivitis, although only a small proportion of gingivitis sites make this transition.112,124,139 What happens in this transition is that supragingival plaque serves as a reservoir for periodontopathogenic organisms,71,201,251 and when this infection is strong enough to overwhelm the host defense, bacteria in supragingival plaque migrate subgingivally to form a subgingival biofilm.180 Inflammatory mediators play an important role in the progression of periodontitis.166,177 A number of microbial species have been associated with destructive periodontitis, although it is unlikely that all of these bacteria are essential players in the disease.179 As is discussed later in this chapter, some of these species have been associated with serious systemic diseases.

Whether or not periodontitis develops after infection, and its severity if it does, are determined by the nature and extent of the host response to these infections. Only some 20% of periodontal diseases are now attributed to bacterial variance, 50% are attributed to genetic variance, and 20% to tobacco use,180 although the contribution of tobacco use may be higher than that.93 Only a small proportion of virtually any population is susceptible to severe, generalized periodontitis, even though most people have these infections to some degree. This has led to the hypothesis that there are two distinct types of periodontitis. One is the plaque and local factors type, the most common form, in which specific pathogens dominate the host response in controlling disease expression; the second is the compromised host type, in which severity and rate of progression are often rapid and are not well correlated with local factors like plaque deposits.166 The compromised host type is less common, responds much less favorably to standard treatments, and is thought to be the type of disease found in aggressive and diabetes-associated periodontitis. Neutrophil abnormalities have been associated with the compromised host form of the disease,178 and at least in aggressive periodontitis the compromised host response is thought to be of genetic origin.50

Many different classifications of periodontal diseases have been proposed; their evolution is well documented in the various world workshops held down the years. These workshops are international gatherings of experts to review the state of knowledge in the periodontal field and were held in 1966,191 1977,110 1989,163 and 1996 (reported in the first issue of Annals of Periodontology). A subsequent workshop in 1999, held to review disease classifications, produced the list shown in Box 21-1. This classification is far more detailed than its predecessor.163 It is becoming increasingly accepted that the periodontal diseases are a family of more or less related conditions, and advances in molecular biology will most likely provide new bases for classifying them in the future.

BOX 21-1 Summarized Classification of Gingival and Periodontal Conditions11

Although these different categories of periodontitis are widely recognized, there are no generally accepted definitions of serious or moderate periodontitis, terms widely used in clinical practice, epidemiology, and public health. Several definitions of serious periodontitis that have been used in epidemiologic studies are shown in Box 21-2. Two of these definitions use CAL plus the presence of pockets, whereas the third is based on a cutpoint on a statistical distribution. When the term serious or severe periodontitis is used in this chapter, the reference is to a degree of periodontitis severe enough to cause or threaten the loss of teeth. There is moderate agreement in the literature that CAL of 6 mm or more is a reasonable cutoff point to differentiate serious from moderate periodontitis; the latter term is usually applied to CAL of 4-5 mm or less. Moderate periodontitis is used in this chapter to mean periodontitis in which pocketing, CAL, or even some bone loss can be clinically or radiographically demonstrated, but the condition is not yet severe enough to threaten the loss of teeth.

CURRENT MODELS OF PERIODONTAL DISEASES

As mentioned in Chapter 16, perceptions of the nature of periodontal diseases changed radically as a result of research during the 1980s and 1990s. The old view of periodontal disease before that time is summarized in the following statement from a 1961 report by an expert committee of the World Health Organization (WHO):

Periodontal disease is one of the most widespread diseases of mankind. No nation and no area of the world is free from it and in most it has a high prevalence, affecting in some degree approximately half the child population and almost the entire adult population. Research and clinical evidence indicate that the damage caused to the supporting structures of the teeth by periodontal disease in early adult life is irreparable, while in the middle adult life it destroys a large part of the natural dentition and deprives many people of all their teeth long before old age. The total effect of periodontal disease on the general health of the populations is unassessable.250

This whole passage conjures up a vision of helpless peoples, all equally susceptible and suffering en masse. It was also accepted at that time that gingivitis invariably progressed to periodontitis, a view that has now changed to recognition that few gingivitis lesions actually make that transition.

Challenges to the concept of universal susceptibility came with epidemiologic studies in low-income countries. These surveys yielded broadly similar results in that they found massive deposits of plaque and calculus, and thus high levels of gingivitis.21 But contrary to expectations, they also found that the prevalence of serious, generalized periodontitis in these poorer countries was little different from that in the highly treated populations of high-income countries.16,17,19,122,131,170 Further substantial modification to the traditional perception of periodontitis came with the demonstration in the early 1980s that the periodontal tissues apparently had the capacity to repair themselves.75 This finding was incorporated into what became known as the burst theory of periodontitis,211 which essentially states that periodontitis progresses in a series of relatively short, acute bursts of rapid tissue destruction, followed by some tissue repair and long periods of remission.125 This view was the converse of the hypothesis of linear progression that had been assumed until that time and resulted from analyzing measurements from individual sites rather than using pooled data as had been done before. The burst theory of periodontal destruction has been accepted by most researchers, and there is now good epidemiologic evidence to support it.28

Basic, clinical, and epidemiologic research from around the late 1970s onward (about the same time that the caries decline was recognized) has therefore led to a perception of the periodontal diseases that can be summarized as shown in Box 21-3.

BOX 21-3 A Current Model of Periodontal Diseases

Although periodontal diseases are constantly becoming better understood, the measurement problems described in Chapter 16 have not gone away. We are still not confident about how to separate susceptible from nonsusceptible people and active from inactive sites.174 Until research finds a suitable way of measuring active disease, then CAL, pocket depth, radiographic bone loss, and gingival bleeding must serve as measures of periodontal diseases, cumbersome and inappropriate for some purposes though they are.

DISTRIBUTION OF PERIODONTAL DISEASES

Geographic Distribution

Over 70% of adults in all parts of the world have some degree of gingivitis or periodontitis.20 Under the old perception of periodontal disease, it was considered that prevalence and severity were greater in low-income countries than in the higher-income world. However, data collected since 1980 in WHO’s Global Oral Health Data Bank,187,188 when added to the results of other epidemiologic studies,15 suggest that, although gingivitis and calculus deposits are more prevalent and severe in low-income nations, there are fewer global differences in the prevalence of severe periodontitis. Gingivitis and calculus deposits can be controlled by personal oral hygiene and professional dental care, so it is to be expected that they are less severe in high-income nations. This geographic profile, in which severe periodontitis is not clearly dependent on the presence of plaque and calculus, is consistent with the compromised host model of periodontitis described earlier.

Prevalence of Gingivitis

At the population level, gingivitis is found in early childhood, is more prevalent and severe in adolescence, and tends to level off after that. The prevalence of gingivitis among schoolchildren in the United States has been around 40%-60% in various national surveys.235 In a national survey of employed adults in 1985-86, 47% of males and 39% of females ages 18-64 had at least one site that bled on probing.237 In the first national survey of adults that measured gingivitis, conducted in 1960-62, some 85% of men and 79% of women were affected.234 Even with allowance for the differences between the two surveys in measurement techniques and the populations studied, it seems fairly clear that there has been an improvement in gingival health over that period.171

Gingivitis is closely correlated with plaque deposits, a relationship long considered one of cause and effect. Studies of the natural history of periodontal diseases in Norway and Sri Lanka found no increase in prevalence and severity of gingivitis between the late teen years and age 40. In Norwegian professionals and students, among whom oral hygiene was excellent,8 and in Sri Lankan tea workers, among whom gingival conditions and oral hygiene were poorer, there was no age-related increase in gingivitis. Surveys in other low-income countries show that gingivitis, associated with extensive plaque and calculus deposits, is the norm among adults.15

Prevalence of Periodontitis

Interpretation of epidemiologic data from before 1980 or so is difficult because the indexes used to measure the conditions before that time are no longer considered valid (see Chapter 16). The impression created by these data was that summed up in the WHO quotation given earlier: “periodontal disease” was uniformly extensive and serious in most populations. Later research, however, in which the use of disaggregated indexes in epidemiology played a prominent part, has led to an almost total reversal of that concept. Data from many parts of the world have now shown that the prevalence of generalized, severe periodontitis is in the range of 5%-15% in almost all populations, regardless of their state of economic development, conditions of oral hygiene, or availability of dental care.15,51,112,229 This relatively low proportion supports a fundamental shift away from the old view of universal susceptibility, even though it still represents a lot of people with serious periodontitis.

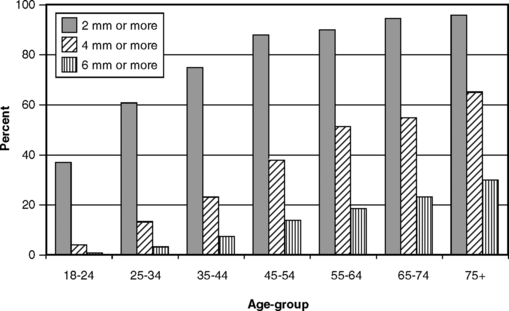

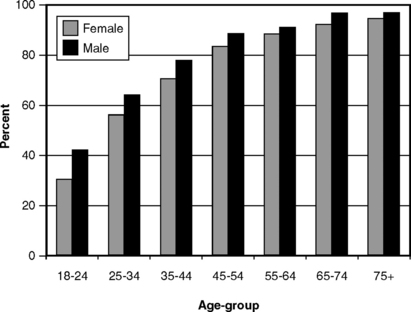

Any assessment of the prevalence of a condition, and the form of its distribution in a population, must begin with a case definition of the disease. Here is the first difficulty, for as described earlier there is no clear agreement on how to define moderate and serious periodontitis. We stated earlier that 6-mm CAL is generally considered serious and 4- to 5-mm CAL moderate, but to many it seems reasonable to say that any CAL should be considered disease. Philosophically that may be true, but in practical terms considering all CAL as disease is not helpful. To illustrate this point, Fig. 21-1 graphs the proportion of adults in the United States with at least one site showing 2-mm CAL. A high proportion of even the younger age-groups is affected, and the condition soon becomes almost universal. CAL of at least 2 mm is so common, and is so often found in persons with functional dentitions, that one has to wonder whether philosophically it should be thought of as disease in a clinical sense. Certainly any criterion that is so commonly met is not useful in epidemiologic research in which risk factors are being sought.

Fig. 21-1 Proportion of U.S. adults with at least one site showing clinical attachment loss of 2 mm or more by age and gender, 1985-86.233

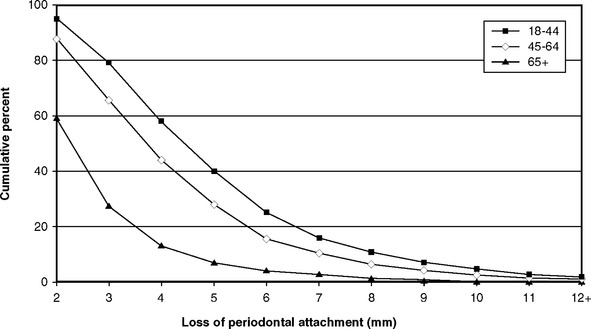

CAL is considered to be the most valid measure of periodontitis,74 even though it measures past disease rather than present activity. If CAL of 2 mm is too common to discriminate between people who are susceptible and those who are not susceptible to serious periodontitis, then where should the cutoff be? Fig. 21-2 graphs the proportion of adults with at least one site showing CAL of 2 mm, 4 mm, or 6 mm, and Fig. 21-3 shows the skewed distribution of CAL in three age-groups. If the use of a 2-mm measure is not sensitive enough (i.e., includes too many false negatives), a 6-mm cutoff may be not specific enough (i.e., it could exclude too many true positives). We stated earlier that CAL of 4-5 mm has generally been considered moderate periodontitis in the literature, so CAL of at least 3 mm, at the upper end of mild periodontitis, seems a reasonable basis for a case definition of periodontitis. In incidence studies, 3-mm CAL is usually taken as the criterion for incident periodontitis because this level is outside the change that could reasonably be attributed to error by a trained, experienced examiner.25

Incidence of Periodontitis

Longitudinal studies of periodontitis onset and progression in community-dwelling populations are inherently expensive and difficult, so it is not surprising that only a few have been conducted. One was the Piedmont project in North Carolina, so named for the five-county geographic region in which a community-dwelling sample (i.e., neither institutionalized nor taken from patient lists at a dental school) ages 65-80 years, mostly rural and of low income, received a series of periodontal examinations in their own homes over 5 years. Periodontal conditions in this group were generally not good. Although the mean number of affected sites at baseline was only a little more than that found in younger age-groups, the severity of disease at those sites was considerably greater.26 When disease incidence (defined as an increase in CAL of at least 3 mm) was assessed for the first 18 months and for the second 18 months separately, CAL during the first period was positively related to CAL in the second period at the level of the individual but not at the site level.24 These findings were confirmed at the 5-year examination: the presence of CAL in the first period did not put a site at risk for CAL in subsequent periods.27 These findings support the episodic, randomized model of periodontitis in susceptible persons. At the mesiobuccal sites examined, increased pocket depth rather than gingival recession accounted for most disease incidence, whereas for buccal sites gingival recession accounted for most incidence.23 The research team found that risk factors were not the same as prognostic factors (their term for risk factors related to the progression of existing disease). However, counted among both risk and prognostic factors were low income, tobacco use, presence of specific bacteria, and use of medications likely to result in soft tissue reactions.

A longitudinal project of major importance was the 15-year study of periodontitis among 480 tea workers in Sri Lanka.131 The group studied had virtually no dental treatment of the type found in developed countries, so the data reflected the natural history of periodontitis. Based on tooth loss and interproximal CAL over the 15 years of the study, it was concluded that some 8% demonstrated rapid progression, 81% moderate progression, and 11% no progression beyond gingivitis. This study provided important evidence demonstrating the range of susceptibility to periodontitis. A subsequent finding on disease incidence in this group was that gingival recession progressed over time on virtually all surfaces, whereas in a comparison group of high-income Norwegians it was largely confined to the buccal surfaces. The buccal-only recession was thought to come from toothbrush abrasion, whereas the all-surfaces recession among the Sri Lankans was seen as plaque related.130

Clinical studies that have followed groups of patients over a period of time have contributed valuable information toward the understanding of periodontitis.73,84,127 These should not be called epidemiologic studies, for when patients are followed then all participants, by definition, are susceptible to the disease. Although epidemiologic research is better for defining risk factors, clinical studies are valuable for studying disease progression in susceptible individuals.

DEMOGRAPHIC RISK FACTORS IN PERIODONTITIS

Gender and Race or Ethnicity

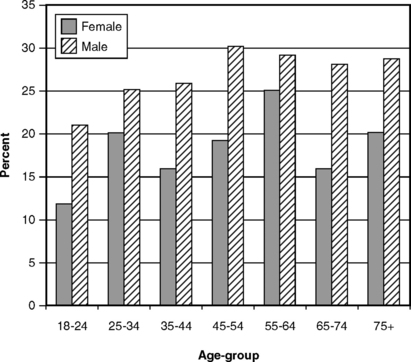

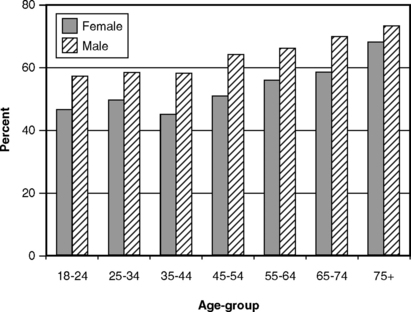

Surveys of periodontal conditions usually show that men have poorer periodontal health than women. This has long been observed and is still the case in the most recent national survey in the United States. Figs. 21-1, 21-4, and 21-5 show that, as measured by CAL, the presence of pockets, and subgingival calculus, women consistently look better than men. In older surveys234,236 this finding was obscured by the greater tooth loss among women, tooth loss that was assumed to reflect the ravages of periodontal disease. More recently, however, differences in tooth loss between the sexes are no longer evident (see Chapter 19). Women usually exhibit better oral hygiene than do men,237 which would explain the differences seen in gingivitis. The fact that women show less subgingival calculus (see Fig. 21-5) is likely to contribute toward their better periodontal conditions as measured by CAL and pocket depth. Current knowledge of the pathogenesis of periodontitis, when added to the epidemiologic evidence, indicates that there are no inherent differences between men and women in susceptibility to periodontitis.

Fig. 21-4 Proportion of U.S. adults with at least one periodontal pocket of 4 mm or more by age and gender, 1988-94.233

Fig. 21-5 Proportion of U.S. adults with at least one site showing subgingival calculus by age and gender, 1988-94.233

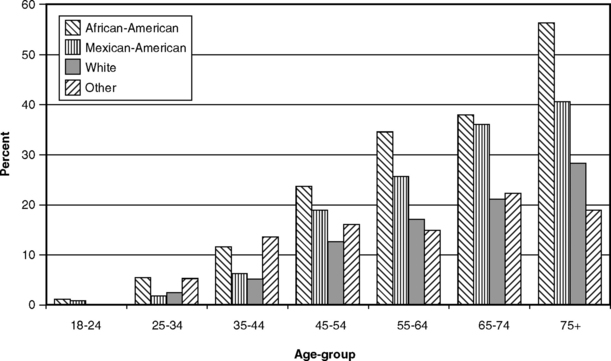

There is also little evidence to suggest different susceptibility to periodontitis among different races. Early epidemiologic studies showed considerable differences between nations190,198 but no consistent associations with race or ethnicity when persons of the same age and oral hygiene status were compared. Reviews presented at world workshops in 1966243 and 197744 also found no differences in disease prevalence that could be attributed to race or ethnicity, and that view essentially still prevails.15 On the other hand, in the 1986-87 national survey of schoolchildren, the prevalence of CAL (at least one site with attachment loss of 3+ mm) in 13- to 17-year-olds was 10% among African-Americans, 5% among Hispanics, and only 1.3% among whites.3 These data did not account for socioeconomic differences, so the differences seen may not be attributable to race or ethnicity.

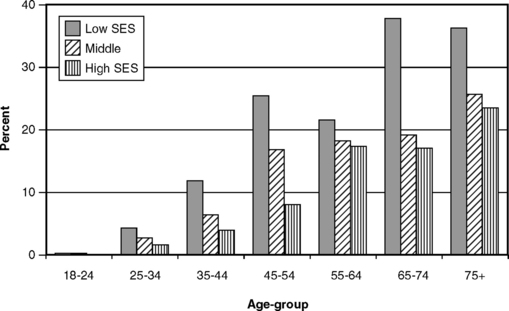

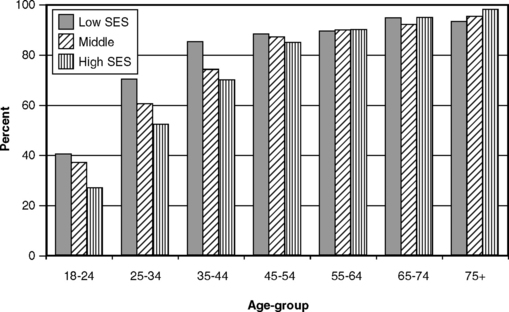

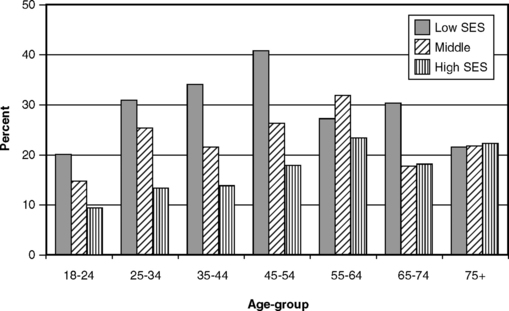

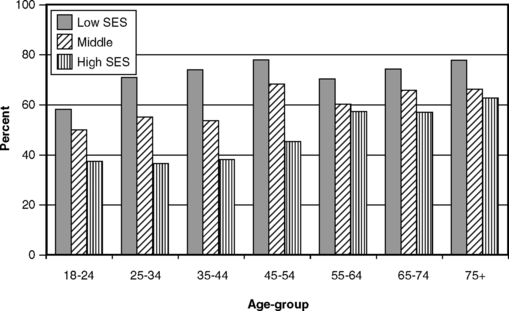

Fig. 21-6 shows the extent of severe CAL in the United States by socioeconomic status (SES), and Fig. 21-7 shows the prevalence of severe periodontitis among four racial-ethnic groups in the United States in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) of 1988-94. Data in these charts are not consistent from one age-group to another except that prevalence is higher at all ages among African-Americans, and this pattern is likely to be associated with SES rather than to reflect true racial differences. The WHO Global Oral Health Data Bank, which maintains data from many nations collected using the Community Periodontal Index, suggests a rather remarkable uniformity of conditions around the world.187,188 Overall, the evidence indicates that race and ethnicity in themselves cannot be considered as demographic risk factors for periodontitis.

Age

The relationship between age and periodontitis is not always an easy one to understand. Much of the problem dates back to the older perception of the disease, in which the interpretation of cross-sectional survey data was generally that the severity of the disease increased with advancing age. However, today we do not view periodontitis as a disease of aging. The greater prevalence and severity of CAL in older people in cross-sectional surveys come not from a greater susceptibility in older people but from the cumulative progression of lesions over time.35

Fig. 21-2 shows the distribution of degree of CAL at the most affected site among adults as measured by NHANES III in United States during 1988-94. These cross-sectional data show that there is a linear relationship between age and the proportion of people with at least one site with 4-mm or 6-mm CAL. By contrast, the proportion of people with at least one site with 2-mm CAL rises rapidly with age and then tends to flatten out at a high level. This suggests that people who get only this low level of periodontitis get it early in life, and as discussed previously it is too common to be of value in discriminating between disease and nondisease.

Fig. 21-4 shows that the relationship between age and the presence of at least one pocket of 4 mm or more is not as direct as that found with CAL. If pockets are taken to reflect active disease (as opposed to CAL, which is a “scar” of past disease), then this weak relationship with age is not surprising.

Age-related findings were a feature of the Sri Lankan studies described previously.131 Earlier reports of these researchers compared the Sri Lankans with a group of college students and professors in Oslo, Norway, a dentally conscious group.8,132,133 The oral hygiene status of the Oslo group was excellent, with no increase in the prevalence and severity of gingivitis from the late teenage years to around 40 years of age. Mean annual CAL in the Oslo group was 0.07-0.13 mm. The Sri Lankan group was followed for 15 years, and as described earlier participants could be categorized into three groups in terms of rate of disease progression: rapid, moderate, and little to none. In the first two groups, periodontitis progressed with age, although naturally much more so in the rapid-progression group, virtually all of whom were edentulous by 40-45 years of age. In the moderate-progression group, the annual mean rate of CAL increased from 0.3 mm when the members were in their twenties to 0.5 mm 15 years later. By contrast, annual CAL in the rapid-progression group averaged 1.04 mm when they were ages 25-29. In the nonprogressing group, average annual CAL was around 0.05 mm and did not change with age.

Rather than showing an increased susceptibility to periodontitis with increasing age, post-1980 epidemiologic studies support the view that those who retain their teeth into old age are likely to be the less susceptible individuals. When periodontitis occurs in susceptible persons, it starts young.* None of these studies demonstrating moderate CAL in young people followed their subjects into later life. These young people may fit the compromised host disease model,166 although without case-control studies or additional longitudinal data this cannot be stated for sure. It fits the pattern of many diseases, however, if the persons most susceptible to periodontitis are those who exhibit the disease in their youth. (We should note that we are not referring here to the specific condition of aggressive periodontitis, which is thought to affect some 0.1%-0.2% of the adolescent population.)239

The likelihood that older dentate people may be of low susceptibility is strengthened by the finding that serious disease is not as common among such groups as once thought. As shown in Fig. 21-3, the distribution of people by their most severe CAL site is skewed, and this skewed distribution is largely independent of age.91 Other analyses of cross-sectional national survey data have also concluded that age is not a major determinant of periodontitis.1,36

Even though there are indications from clinical studies that the aging periodontium does not tolerate plaque as well as it used to, that the nature of the plaque itself may change with age, and that the periodontium recovers from injury more slowly, these potential problems are overshadowed by the patient’s susceptibility to disease.238 This further supports the idea that, when a patient is susceptible to periodontitis, the tendency is seen early. Adult periodontitis in the elderly is characterized by infrequent and slow progression, and does not usually lead to tooth loss. Even in cases in which periodontitis is reported as a leading cause of tooth loss in the elderly (see Chapter 19), it is likely that a lot of the teeth extracted then have been seriously diseased for years rather than becoming that way in old age.

Socioeconomic Status

Generally, those who are better educated, wealthier, and live in better circumstances enjoy better health status than the less educated and poorer segments of society. Many disease conditions are associated with SES, a complex variable that can subsume a lot of cultural factors. Periodontal diseases are among this group13,225 and have historically been related to lower SES.234,236 The periodontal ill effects of living in deprived circumstances can start early in life.206

Gingivitis and poorer oral hygiene are clearly related to lower SES, but the relationship between periodontitis and SES is less direct. Fig. 21-8 shows that there are obvious SES differences only among younger people when CAL is 2 mm or more, but as we have stated several times already, CAL of 2 mm is not a sensitive measure. When those with CAL of at least 6 mm (see Fig. 21-6) are classified by SES, a more consistent difference is seen, especially at younger ages. As shown in Fig. 21-9, when the measure is the prevalence of pockets of at least 4 mm, differences are also seen between SES strata and are most pronounced among the young. Subgingival calculus deposits are also more prevalent among lower SES groups (Fig. 21-10).

Fig. 21-8 Proportion of U.S. adults with at least one site showing clinical attachment loss of 2 mm or more by age and socioeconomic status (SES), 1988-94.233

Fig. 21-9 Proportion of U.S. adults with at least one periodontal pocket of 4 mm or more by age and socioeconomic status (SES), 1988-94.233

Fig. 21-10 Proportion of U.S. adults with at least one site showing subgingival calculus by age and socioeconomic status (SES), 1988-94.233

The widely observed association between SES levels and gingival health is a function of better oral hygiene among the more educated and a greater frequency of dental visits among the more dentally aware and those with dental insurance (who are more likely to be white-collar employees, i.e., those with more education). SES is a complex and multifaceted variable, and it is virtually impossible to remove the effect of SES as a confounder in the race-ethnicity associations seen in Fig. 21-7.

Genetics

The first report identifying a genetic component in periodontitis appeared in 1997.113 Most of the research studies relating to genetics as a determinant of disease have been laboratory and clinical investigations rather than epidemiologic studies but they should still be briefly considered here.

The original 1997 report, based on data from patients in private practices, found that a specific genotype of the polymorphic interleukin-1 (IL-1) gene cluster was associated with more severe periodontitis. This relationship could only be demonstrated in nonsmokers, which indicated immediately that the genetic factor was not as strong a risk factor as was smoking. The IL-1 gene cluster has received a lot of research attention since then. This is appropriate, given that the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 is a key regulator of the host response to microbial infection,147 although IL-1 is unlikely to be the only genetic factor involved.142 IL-1 has been identified as a contributory cause of periodontitis among some patient groups53,

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses