Long Face Growth Patterns

Maxillary Vertical Excess with Mandibular Deformity

• The Role of Growth Modification in the Preadolescent Patient

• The Orthodontic Camouflage Approach

• An Orthodontic Molar Intrusion Approach

• Postsurgical Orthodontic Maintenance and Detailing

• Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

• Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

• Temporomandibular Disorders: Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

The prevalence of a long face growth pattern at a prominent U.S. maxillofacial center was documented as representing 22% of jaw deformity evaluations as judged from the parameter of excessive anterior facial height.114 The lower anterior facial height was specifically long in 88% of the affected individuals.54,74,75 The term long face is generally used to describe a maxillofacial growth pattern that typically also includes a gummy smile, an anterior open bite, and a lack of chin prominence. This combination of problems seems to be harder for the individual to live with; it results in a personal and family decision to seek treatment more frequently than most other patterns of dentofacial deformity (e.g., mandibular deficiency alone).112 Halfway around the world, in South Africa, Reyneke estimated that, in his orthognathic practice, approximately 30% of those seeking treatment have a long face with complaints about a gummy smile and concerns caused by malocclusion.117

The basic diagnostic criteria for a long face growth pattern include an excessive anterior facial height (i.e., the elongation of the lower third) that leads to disproportion between facial height and width.26,28,69,70 Studies confirm that the excessive eruption of the posterior maxillary dentition causes the mandible to rotate downward and backward (clockwise rotation) and results in increased lower facial height.24,34 This makes any baseline mandibular anteroposterior deficiency seem worse and any true mandibular prognathism seem better.31,123 As the mandible rotates down and back during facial development, the lower incisors often adapt by becoming more upright, with crowding. The mandibular clockwise rotation tends to separate the upper and lower incisors vertically, thereby creating an open bite with an accentuated curve of Spee.76 Not all long face growth patterns involve an anterior open bite. The maxillary incisors also supra-erupt.111,139 The anterior bite may stay closed or even become deep, depending on the extent of maxillary and mandibular incisor supra-eruption.5,23,71,93–97,133 Whether the incisor relationship remains deep, normal, or open, lip incompetence (i.e., ≥4 mm of lip separation at rest) occurs, with mentalis strain that results from attempts to achieve lip closure.27,99,100

Functional Aspects

• Wide lip separation occurs, with excessive effort required during attempts to achieve lip seal.

• Chronic obstructive nasal breathing as a result of increased intranasal airway resistance (e.g., septal deviation, enlarged inferior turbinates, tight nasal aperture, elevated nasal floor) is frequent (see Chapter 10).

• Classic articulation errors in speech as a result of the anterior open bite and lip incompetence are expected (see Chapter 8).

• Chewing and swallowing difficulties caused by the anterior open-bite malocclusion are expected (see Chapter 8).

• Detrimental effects on the dentition and the periodontium as a result of long-term traumatic malocclusion, the displacement of the teeth outside of the alveolar bone housing, or previous camouflage orthodontic and restorative treatments may be seen.

• The incidence of temporomandibular disorder may be higher than it is among individuals with normal jaw harmony and occlusion (see Chapter 9).

Clinical Characteristics

• Excessive anterior facial height, primarily in the lower third of the face

• Lip incompetence (i.e., resting lip separation of ≥4 mm)

• Increased exposure of the gingiva with a broad smile (i.e., a gummy smile)

• Increased frequency of anterior open bite (although one third of patients present with a normal or deep bite and only 15% have an open bit of >4 mm)

• Mandibular deficiency with Class II malocclusion is frequent (this can range from Class I to Class III)

• A mandible that is rotated downward and backward (i.e., clockwise rotation)

• An excessively full, curled lower lip when in a relaxed position

• Increased vermillion exposure of the lower lip

• A constricted or narrow alar base width, with depressed paranasal regions

• The appearance of a flat or sunken midface, without aesthetically pleasing facial curves or contours

• A negative vector relationship of the ocular globe to the lower eyelid

Dental Findings

• Anterior open bite (may be normal or deep)

• Excessive alveolar height in the anterior maxillary region (this will raise the floor of the nose and partially obstruct nasal airflow)

• Mandibular incisors that are upright, with crowding

• Accentuated curve of Spee as a result of the overeruption of the mandibular incisors

• Tendency toward a narrow, V-shaped maxillary arch with posterior crossbites (this is seen in approximately 50% of patients)

• Occlusal surface enamel wear on the posterior teeth as a result of grinding (secondary occlusal trauma) or previous occlusal equilibration performed in an attempt to close the anterior open bite

Radiographic Findings

• Excessive eruption of the maxillary posterior teeth (i.e., the distance from the palatal plane to the cusps of the molars)

• Maxillary horizontal deficiency

• Clockwise rotation of the maxilla (i.e., an increased palatal plane angle)

• Increased lower anterior facial height

• Clockwise rotation of the mandible (i.e., an increased mandibular plane angle)

• Normal or short mandibular ramus height

• Mandibular posterior teeth not excessively erupted

• Excessive eruption of the maxillary and mandibular incisors: with enough anterior hypereruption, a normal or deep overbite is more likely

• Measurable excessive eruption of the maxillary incisors (i.e., the distance from the floor of the nose to the incisal edge)

• Measurable excessive eruption of the mandibular incisors (i.e., the distance from the menton to the incisal edge)

Fields and colleagues presented simplified cephalometric diagnostic criteria.44 If a patient has all three of the following criteria, he or she can be considered to have a long face growth pattern:

Etiologic Considerations

Current thinking is that both environmental influences and inherited tendencies play a role in the development of a long face.53,66,67,85–87 A significant percentage of patients with long faces have been found to have an increased oral and decreased nasal breathing pattern.25,33,37,52,59,82,134,146,150 Interestingly, nasal obstruction is not always present with long face growth patterns, but an open-mouth posture during development is typical. Other causes of an open-mouth posture in the preadolescent patient have been shown to result in similar long face dysmorphology.1,2,4,51,61,78,80,140 This includes muscle weakness syndromes (e.g., Moebius syndrome, facial nerve palsy, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy) and the presence of a large tongue (e.g., Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, hemangioma, vascular malformations, neurofibromatosis, Proteus syndrome; see Chapter 4).

There is experimental animal model research to support the theory that a long face anterior open-bite malocclusion is a physiologic adaptation to an open-mouth protrusive tongue posture that is present during facial development (see Chapters 4 and 10).62–65 It has also been clarified that, in humans, a resting open-mouth protrusive tongue posture is an etiologic factor in the development of a long face with an anterior open bite. Interestingly, the intermittent occurrence of tongue thrust during speech and swallowing is not thought to be the cause of an open bite. In fact, periodic tongue thrusting is an adaptive response to an open bite rather than the cause.47 When the incisors overlap in an average way (i.e., with a normal overbite), the normal-sized tongue is naturally placed behind the teeth to create the necessary anterior seal for successful swallowing and the articulation of specific consonant sounds (see Chapter 8). In the presence of anterior open bite, the normal tongue must protrude past the teeth to seal against the lips. This is an expected adaptive mechanism to assist with swallowing and speech. Confirmation that the protrusive tongue position during swallowing and speech is a reversible adaptation has been routinely documented after the individual with a long face and an anterior open bite undergoes successful orthognathic surgery and orthodontic treatment.89,142,155 When the open bite is closed with the use of sound biologic mechanics (i.e., without orthodontic dental compensation) and when lip competence is achieved through surgery (i.e., there is no longer excess lower facial height), there is a fairly reliable elimination of the tongue thrust without the need for active myofunctional physical therapy retraining. However, if a skeletal anterior open bite has been closed with the use of unsound orthodontic maneuvers (i.e., excessive eruption of the anterior teeth or buccal tipping of the molars outside of the alveolar bone housing) and if lip competence is not achieved (i.e., inadequate facial height shortening), dental relapse is to be expected. In this case, tongue thrusting should not be blamed for the recurrent malocclusion.

An Orthodontic Molar Intrusion Approach

Sato and colleagues believe high-angle Class II malocclusions can be corrected with the use of “multiloop edgewise arch wires.”124 With the use of tip-back mechanics and vertical elastics, the researchers believe that the occlusal plane inclination can be altered by intruding the molars via the autorotation of the mandible and the closure of the open bite. Unfortunately, scientific evidence in support of this method of treatment for a patient with a long face and an anterior open bite has not been forthcoming.

With the use of skeletal temporary anchorage devices, the intrusion of the molars has been recommended by some to close an open bite.105,157,158 Man-Suk and colleagues completed a study to examine the long-term stability of anterior open-bite correction via the intrusion of the maxillary posterior teeth in adults.88 In the first group (n = 5 adults), mini-screw implants were placed on the buccal and palatal sides, between the roots of the maxillary second premolars and first molars and between the roots of the maxillary first and second molars. Intrusion forces were directly applied to the molars with elastomeric chains. In the second group (n = 4 adults), mini-screw implants were placed on the buccal side only between the roots of the maxillary second premolars and first molars and between the roots of the maxillary first and second molars. A rigid transpalatal arch was placed before applying the intrusive forces to prevent the buccal tipping of the teeth. Lateral cephalograms were taken at the initial evaluation and again at 1 and 3 years after treatment. The cephalograms were traced and analyzed. The study documented that the maxillary first molars were intruded on an average of 2.39 mm during treatment, with relapse of 0.45 mm at the 3-year follow up (i.e., 22.9% relapse). A majority of the relapse occurred during the initial posttreatment year. The molar relapse had a significant effect on the eventual incisal overbite. There was no significant difference in molar relapse or the maintenance of overbite between the two different methods of skeletal anchorage used. It would appear as though there is currently no known way to fully retain an orthodontically intruded molar.

For patients with borderline long face growth patterns in whom the open bite has been successfully closed with the use of orthodontic mechanics and in whom the remaining gummy smile and lip incompetence is only mild, a vertical reduction with horizontal advancement genioplasty may improve the profile aesthetics and lip competence enough to be a satisfactory compromise for the patient (see Chapter 37 and 40).

Definitive Reconstruction

Timing of Orthognathic Surgery

Orthodontic or surgical interventions undertaken in the individual with a long face growth pattern will not be definitive if significant jaw growth continues after treatment. In our experience, when the increased intranasal airway resistance is simultaneously managed as part of the definitive jaw reconstruction, excessive ongoing vertical growth ceases.108,110 Even if minor degrees of vertical growth were to continue, it should occur in both the mandible and the maxilla in a proportionate way.

Horizontal jaw growth maturation may be analyzed with the use of serial lateral cephalometric radiographs. These sequential radiographs can be used to make direct mandibular measurements. Surgery is delayed until the deceleration of growth can be documented. The best evidence available indicates that, when orthognathic surgery is undertaken in the mandibular-deficient patient as early as completion of the adolescent growth spurt, forward growth of the mandible almost never occurs.135 Further horizontal growth of the maxilla at this age is also not expected.

For all of these reasons, proceeding with definitive orthognathic and intranasal surgery for the patient with a Class II long face growth pattern when he or she is as young as 14 years old is generally safe from a growth perspective, but only after the eruption and orthodontic alignment of the teeth (Fig. 21-4).

Preorthodontic Periodontal Considerations

Orthodontic attempts to compensate the occlusion in the patient with a long face growth pattern may result in gingival recession along the labial aspect of the lower incisors and the buccal aspect of the posterior maxillary teeth. The advantage of bicuspid extractions in the mandible or the maxilla should always be considered to achieve full positioning of the dental roots solidly in the alveolar bone (see Chapter 6).

When lip competence and an improved nasal airway have been achieved as a result of jaw and intranasal procedures, the dryness of the gingiva (ex. inflammation) will also diminish (see Chapter 6).

Orthodontic Preparation for Orthognathic Surgery

The orthodontic mechanics should be oriented toward positioning of the teeth solidly in the alveolar housing within each arch and specifically within each maxillary segment as indicated.128,132,145,149,151 A goal is for the teeth to occlude together appropriately at the time of surgery and after finishing orthodontics. The preferred and anticipated occlusion is best confirmed via the periodic review of dental models (see Chapter 5).

With maxillary surgical segmentation planned, the orthodontist’s presurgical goal is to level the teeth independently within each segment. With a decision made to also defer arch expansion to the surgical phase (i.e., segmental osteotomies with widening), the orthodontic alignment of the teeth within each segment becomes the preoperative objective. Furthermore, there is no need or advantage for the orthodontist to create a space at the planned interdental osteotomy sites (i.e., between the lateral incisor and canine on each side or between the central incisors), because the roots are naturally divergent (see Chapter 17). The orthodontic preparation before surgery should incorporate the following basic concepts:

1. The mandibular arch is leveled with the use of standard orthodontic mechanics before surgery. A patient with a long face does not generally have a severely exaggerated curve of Spee in the lower arch. Therefore, complete leveling is generally carried out before surgery (with or without the need for extractions).

2. The presence of an excessive reverse curve of Spee in the maxillary arch is an indication of a skeletal problem rather than a dental one. Orthodontic leveling of the arch in segments (i.e., four incisors, the canine through the second molar on the left side, and the canine through the second molar on the right side) is generally consistent with the skeletal dysmorphology, and it is carried out before surgery. With the curve of Spee orthodontically leveled in each of the three components, segmental Le Fort I osteotomies will allow for the placement of the three individually leveled components over the orthodontically leveled mandibular arch to achieve the preferred occlusion at operation.

3. The presence of a narrow maxilla is an indication of skeletal dysplasia rather than dental malposition. Orthodontic tooth movement should remain consistent with the narrow skeletal width. Each posterior segment (i.e., the canine through the second molar on the left side and the canine through the second molar on the right side) should be independently orthodontically leveled. Segmentation of the down-fractured maxilla will then adjust the arch width to the orthodontically leveled mandibular arch. If the posterior teeth have not been orthodontically positioned fully within the alveolar housing (e.g., if there is buccal tipping of molars), dental relapse after surgery with a return of the narrow maxillary arch width and the open-bite malocclusion is more likely to occur (see Chapter 17).

Basic Mandibular Arch Mechanics

• Routine orthodontic mechanics are used to level, align, close up spaces, and achieve appropriate arch form in the lower jaw.

• Extraction of a bicuspid in each quadrant (or of a single incisor, in rare cases) or interproximal reduction may be needed in the lower arch to uncrowd the dental crowns, to set the roots solidly in the alveolar housing, and to correct incisor inclination.

Basic Maxillary Arch Mechanics

• In the presence of vertical skeletal discrepancies, presurgical orthodontic stabilization may be achieved with sectional finishing wires that conform to the arch shape of each segment.

• If no vertical segmental skeletal discrepancies exist, then the maxillary arch is leveled with a continuous arch wire. Care is taken to prevent the forward flaring of the incisors. Posterior intrusion mechanics are also avoided, because they predispose the patient to late dental relapse.

• The advantage of bicuspid extractions to position the remaining roots solidly in alveolar housing should always be considered.

• In our experience, planning the interdental osteotomies between the canines and the first bicuspids is rarely preferred. Segmentation in this location is technically more time-consuming for the orthodontist (i.e., precise intercanine width orthodontic detailing becomes necessary), and it is more prone to dental injury and periodontal sequelae (i.e., pocketing and gingival recession) from the interdental osteotomy at surgery.

• Segmentation between the lateral incisors and the canines is generally preferred. When segmenting in this location, it is not necessary or advantageous for the orthodontist to create space at the planned osteotomy sites, because the roots are naturally divergent. The advantages of segmenting the maxilla in this location (i.e., between the lateral incisor and the canine) on each side and then parasagittally (i.e., down the hard palate) include the simplification of orthodontic mechanics, the prevention of periodontal sequelae, and the ability to positively influence incisor inclination without negatively affecting the vertical facial height.

Basic Surgical Approach

The surgical approach for the treatment of a classic long face is best carried out through a combination of osteotomies, including Le Fort I osteotomy in segments, bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies, and oblique osteotomy of the chin (Figs. 21-1 through 21-10).* Management of the anterior neck soft tissues—including cervical soft-tissue flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysmal muscle plication—can also be carried out, if desired (see Chapter 40). The removal of the impacted wisdom teeth is frequently recommended for long-term dental health. If this is planned, it can be accomplished at the same time (see Chapters 15 and 16).

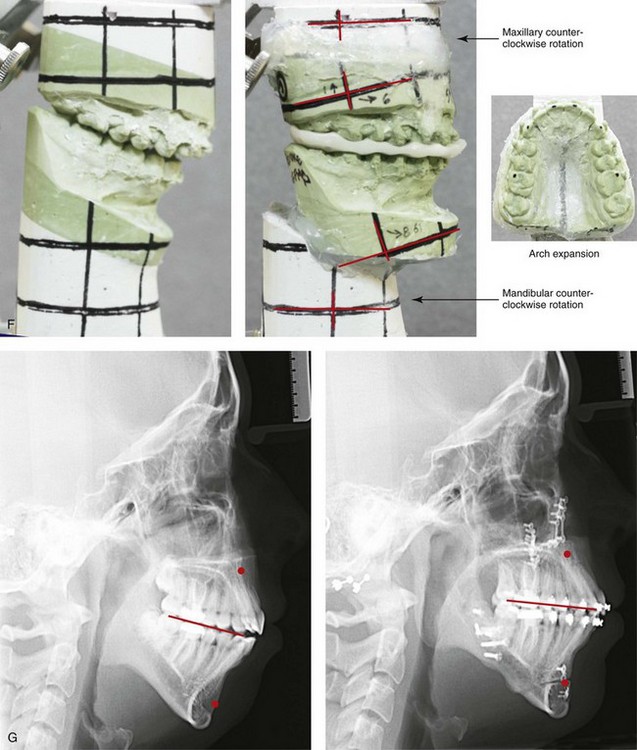

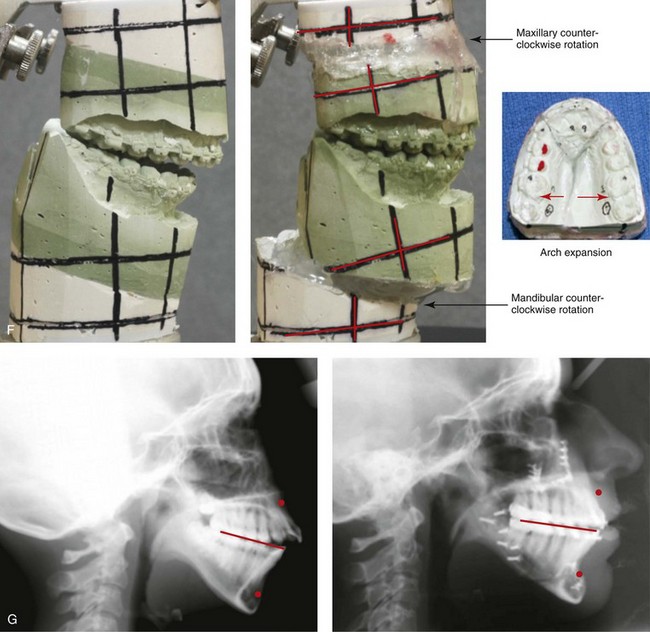

Figure 21-1 A 15-year-old girl arrived with her parents for surgical evaluation. Her history and physical examination confirmed nasal obstruction, heavy snoring, lip incompetence, difficulty chewing, and frequent speech articulation errors. The facial aesthetic concerns included an awareness of a weak chin, a gummy smile, and the impression of having a large nose. The patient had been under an orthodontist’s care since the mixed dentition. Rapid palatal expansion and full bracketing with attempted closure of the anterior open bite were not successful. Further evaluations were carried out by a speech pathologist and an otolaryngologist, and a fresh look was taken at the patient’s orthodontic needs. Orthodontic decompensation in combination with orthognathic and intranasal surgery was chosen. The simultaneous procedures carried out included Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, and vertical shortening, counterclockwise rotation, arch expansion, and the correction of the curve of Spee); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontic decompensation in progress, and after the completion of treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses