Chapter 21

Ear reconstruction

Introduction

The ear plays an important role in facial appearance. Its prominence is not as high compared with the nose but when it is missing, over-projected, or deficient in some capacity, the eyes will be drawn to the defect. Perhaps even more important is the role this deficiency plays on the psyche of the patient.

The reconstruction of auricular defects range from the simple to the complex. The complexity is often associated with the size and composition of the defect. In some cases, a simple skin graft will enable the reconstruction of small to moderate defects. In other instances, the reconstruction will demand a more sophisticated approach due to the complexity of the defect.

Defects affecting the auricle can be broadly divided to traumatic (including burns), oncologic, or congenital (Figures 21.1a, b and 21.2). In rare circumstances defects secondary to infection can lead to the loss of cartilage and therefore deformation of the ear.

This chapter will describe the anatomical features of the external ear and the relevance to reconstruction. Various classifications of auricular defects will be reviewed and finally, the reconstructive options will be discussed. The reconstruction of the microtic ear will not be discussed much as that is not typically encountered in a head and neck surgical practice. Surgeons involved in microtia repair tend to be most commonly, pediatric craniofacial surgeons.

When the defect is encountered secondary to oncological trauma, a thorough understanding of the histology, size of the tumor, and nodal status becomes very important when reconstructive options are being contemplated. The need for adjuvant therapy needs to be determined. For patients who will need to receive adjuvant radiation therapy, undertaking a long multistage reconstruction may not be the most desirable option. Equally, the reconstructive surgeon also has to consider this when reconstructing secondary defects.

Anatomy

External ear anatomy (pinna)

The ear plays a prominent role in our facial esthetics. The anatomy of the external ear is complex due to the intricacies of the convexities and concavities formed by the skin drape over the cartilaginous structure.

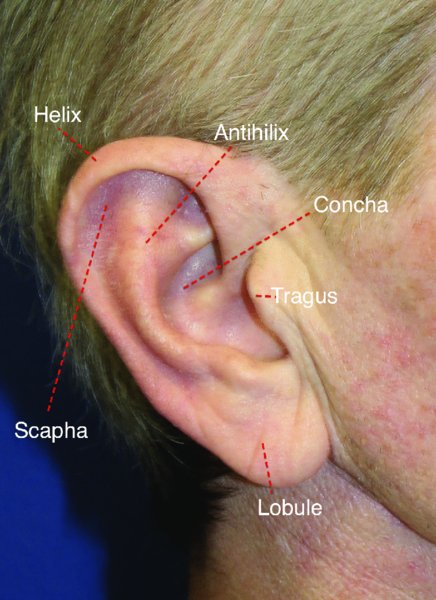

In simple terms, one can divide the ear into large areas: helix and antihelix, the tragus, the concha, and the lobule.

The external ring of the auricle is the cartilaginous helix, anterior and parallel to it lays the Y-shaped antihelix. This cartilaginous concave area at the superior aspect of the auricle between the helix and antihelix is referred to as the scapha. The concave space immediately anterior to the antihelix is the cymba. Between the scapha and the cymba exists a small depression between two convexities (crura); this space is the triangular fossa.

The anterior aspect of the ear at the junction with the cheek is the crus of the helix and inferior to it is the tragus. The external auditory meatus is found in this area and is contiguous with the cavum.

The inferior portion of the auricle is formed by the lobule. The lobule is composed of fat and fibrous tissues and lacks any cartilage (Figure 21.3).

The position of the ear in a cranial caudal and anterior posterior aspect is important, as the spectator can perceive small differences with the contralateral ear. The average head-to-ear angle is 31.1 degrees and for the scapha-to-concha angle it is 106.7 degrees.1

Figure 21.1a View of a patient after traumatic loss of the ear due to an automobile accident.

Figure 21.1b Near amputation of the ear secondary to trauma; only inferior pedicle remains.

Figure 21.2 View of multiple sites of melanoma in the left auricle.

The arterial supply to the ear comes from several vessels. Anteriorly, branches from the superficial temporal artery supply the ear; posteriorly the supply comes from the posterior auricular artery and the occipital artery. The venous drainage comes from the veins accompanying the named arteries.

The external ear receives innervation from the auriculotemporal nerve (anterior superior one-third), the greater auricular nerve (anterior and posterior lower two-thirds), the lesser occipital nerve (posterior superior one-third), and the auricular branch of the vagus, Arnold’s nerve (external auditory canal floor and concha).

Defect classification

Reconstructive options can be categorized by either the characteristics or location of the ear defect (e.g., partial or full-thickness, or upper, middle, or lower third of the auricle) or the type of surgical technique employed.2 The description of the acquired defects as auricular thirds is commonly used and allows the surgeon a quick visual understanding of the location of the defect as well as its potential complexity.

Reconstructive options

The most common defect encountered is a partial helical defect. The helix is the most prominent portion of the ear and is therefore more susceptible to trauma as well as ultraviolet rays, which lead to the development of skin malignancies.

The following section will illustrate various reconstructive options when faced with acquired defects secondary to trauma or primary defects after resection of malignancies affecting the ear.

The cases will demonstrate some reconstructive options for the repair of these varied defects.

Upper third

Case #1

A 78-year-old Caucasian male was referred for evaluation and treatment of a biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma of the upper helix (Figures 21.4 and 21.5). The area was marked for excision and was then resected (Figure 21.6). The defect was then evaluated for immediate reconstruction. The helix was undermined and a Burrow’s triangle was removed in order to advance the helix to obtain primary closure (Figure 21.7).

Figure 21.3 Markings for various subsites of the ear.

Figure 21.4 Initial marking for the resection of a malignant lesion in the helix.

Figure 21.5 Posterior view of the helical lesion.

Figure 21.6 Aspect of the defect after resection of the lesion.

Case #2

An 85-year-old male presented with a small helix lesion which was later diagnosed as a squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 21.8). The area was excised as a triangle or pie shape so as to allow for the primary closure of the defect without significant external defect (Figure 21.9). Once the area was excised, the defect was able to be closed primarily (Figure 21.10).

Figure 21.7 Initial repair after undermining and advancement of the helix to obtain primary closure.

Figure 21.8 Preparation for a V wedge excision of a helical lesion.

Figure 21.9 View of the defect after resection of the lesion.

Case #3

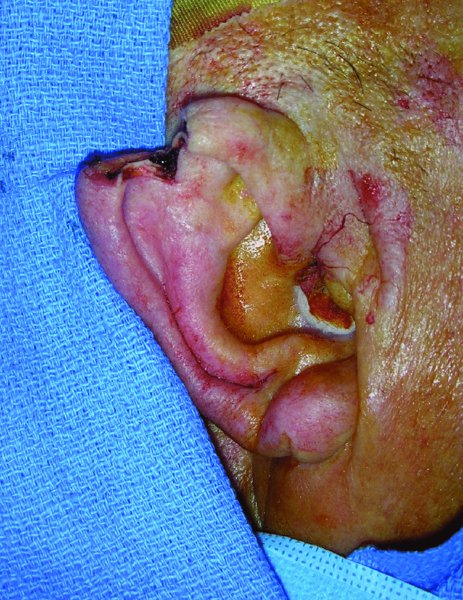

A young man was involved in a motor vehicle accident and suffered loss of the upper and middle external ear. The avulsed ear was de-epithelialized and buried in a pocket in the posterior superior area (Figure 21.11). The patient was later brought back to the operating room where the ear was elevated and skin grafted onto the posterior and superior aspect of the reattached ear (Figures 21.12 to 21.16). The early postoperative appearance of the ear was satisfactory with good take of the graft and appearance (Figure 21.15).

Figure 21.10 Primary repair of the defect with minimal distortion of the ear.

Figure 21.11 Appearance of the left ear after previous trauma and burring of the ear in a soft tissue pocket.

Figure 21.12 Exposure of the buried ear; note the good vitality of the ear.

Figure 21.13 Excellent appearance of the ear and development of the posterior ear flap to be replaced.