2

Outpatient Management of the Medically Compromised Patient

Perhaps the most challenging responsibility for a dentist is to provide care for medically complex outpatients. A thorough history is necessary to establish the existence and nature of any medical problems to adequately assess risk, anticipate complications, and decrease the likelihood of medical emergencies while providing appropriate dental treatment.

Medical History

History taking should elicit information about specific medical conditions, previous hospitalizations, surgeries, allergies, medications, and physician visits in recent years. A thorough social history including drug, tobacco, and alcohol use; sexual history; and social support system should also be included. Standard health questionnaires will often bring out significant information in the history but should not be relied upon as the sole source of information, due to inaccuracies in completing such questionnaires or omissions, intended or otherwise. They should therefore be used as a starting point for a more thorough verbal history (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Example of a Standard Verbal History Taking Format and Content

Hospitalizations: Dates, reason(s) for admission, and outcomes

Operations: Dates, reason(s) for surgery, and outcomes

Drug allergies: Nature, duration, frequency

Medications: Drugs of particular concern

- Oral contraceptives: Reported decreased contraceptive effectiveness with some antibiotics and/or antifungals

- Immunosuppressive drugs: Steroids, cancer chemotherapy, organ anti-rejection drugs

- Antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals: Need to consider the effect on the oral flora and the risk of superinfection

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): This category includes aspirin because of its effect on platelet function, although there is no clear evidence that this is clinically important with regard to bleeding during dental procedures

This chapter is a review (in alphabetical order) of medical problems that are of potential concern to dentists, with emphasis on the essential elements in the medical history, principles of medical care, and oral health care management considerations.

Allergy to Drugs

A drug allergy is an adverse immunologic reaction to a drug (Appendix 3 and Appendix 6, Table A6-2).

Classification

Immunologic drug reactions can be divided into four categories:

- Type I: Immediate in onset and caused by IgE-mediated activation of mast cells and basophils

- Type II: Delayed in onset and caused by antibody- (usually IgG) mediated cell destruction

- Type III: Delayed in onset and caused by immune complex (IgG: drug) deposition and complement activation

- Type IV: Delayed in onset and T-cell-mediated

The World Allergy Association defines two types of immunologic drug reactions:

- Immediate reactions, occurring within one hour of the last administered dose

- Delayed reactions, occurring after one hour but usually more than six hours and occasionally weeks to months after the start of administration

Significance of the Problem

- Type I reactions imply the risk of immediate and life-threatening reactions (anaphylaxis).

- True allergic reactions to local anesthetics are rare, and they represent less than 1% of all adverse local anesthetic reactions. They may be Type I.

- First exposure to a drug can result in an immediate type (Type I) reaction.

- Anaphylaxis may occur with parenteral administration and can last longer if the allergen is administered orally.

Significant Elements in the History

- Sensitivity to any medications/drugs, foods, or materials such as latex, which can cause itching, rash, swelling, or breathing difficulties. Patients should be asked about details of prior experience with specific drugs that might be used in the course of dental treatment (e.g., antibiotics, opioids, aspirin-containing compounds, anesthetics).

- Risk factors include prior history of allergic drug reaction, recurrent drug exposure, certain disease states (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus [specifically amoxicillin], AIDS), atopy (allergic asthma or food allergy) (Appendix 12, Table A12-1).

Evaluating a Patient with a Suspected Allergic Reaction

See Appendix 3. Determine:

- Nature of the allergy

- Previous history of drug allergy and the therapy: drugs administered and the response to them

- Was this the first exposure to the drug? What other medication(s) were taken at the same time (need to exclude drug interaction)?

- Route of administration and dosage: Exclude overdoses or known adverse side-effects (e.g., nausea and vomiting with opioids)

- Time sequence: How soon after injection/ingestion exposure did the allergic reaction occur?

- Be aware of common drugs with significant allergic potential, and alternative medication(s)

- Allergy to local anesthetics must be qualified:

- Procaine: Allergic reaction is more likely than to other anesthetics but procaine is rarely used in contemporary dental practice

- Lidocaine: Allergic reaction can occur but it is extremely rare. A preservative is usually the cause

- Signs and symptoms: Rash/hives, syncope, tachycardia, peripheral vasodilatation, loss of consciousness, breathing difficulty or anaphylaxis

- Take both supine (lying down) and sitting blood pressures

- Use a stethoscope to auscultate the trachea for stridor (i.e., high-pitched wheezing sound) and the lungs for bronchospasm (wheezes)

- Examine the skin for urticaria (hives or rash); examine the mouth and oropharynx for angioedema

- After the nature of the allergy has been determined, it is important to differentiate it from other known drug-related side-effects, such as syncope, gastrointestinal upset, and overdose

- Although many reactions to drugs and foods are not true allergies, do not expose a patient to a substance identified as a possible allergen in a non-hospitalized, uncontrolled setting without access to appropriate resuscitation drugs, equipment, and personnel.

Dental Considerations

- Less than 20% of patients react to the offending drug when challenged. For example, most patients with penicillin allergy lose sensitivity after ten years

- Local anesthetic reactions are most often from intravascular injection, toxic overdose, psychogenic reaction, or an idiosyncratic event

- In cases of documented or suspected allergy, patients should be referred for testing and/or desensitization by an experienced clinician before exposure to the drug in the dental office

Bleeding Disorders

Significant Elements in the History

The past medical and family history can help determine whether the bleeding disorder is the result of an inherited or an acquired problem. Also ask the patient about:

- The details of prolonged bleeding after previous surgery (especially tooth extraction, tonsillectomy, and adenoidectomy). This will help differentiate between local factors and a systemic problem

- Spontaneous bleeding (e.g., nosebleeds, heavy menstrual bleeding, hematuria)

- Easy bruising, petechiae or hematoma formation, or bleeding into joints

- Anticoagulant medications (e.g., warfarin, aspirin, and other antiplatelet drugs)

- Liver, renal or bone marrow disease, or underlying malignancy

- Alcohol or injection drug use

- Significant exposure to radiation, benzene, cytotoxic chemotherapy, insecticides, or other relevant chemicals

- Malabsorption syndrome

Evaluating for Bleeding Disorders: Laboratory Tests

See Appendix 7.

- The three initial screening tests for patients with a bleeding diathesis are platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

- A normal platelet count, normal PT, and prolonged aPTT are characteristic of hemophilia A, hemophilia B, and heparin therapy.

- The PT/international normalized ratio (INR) assesses the extrinsic pathway of clotting (Factors I, II, V, VII, IX, X).

- The aPTT assesses the intrinsic coagulation pathway (prekallikrein, high-molecular-weight kininogen, Factors XII, XI, IX, VIII) and final common pathway (Factors II, V, X, and fibrinogen) and monitors heparin therapy.

- Platelet count is a quantitative measure of platelets.

- Bleeding time is used to characterize platelet function; however, this test is a poor predictor of oral bleeding and has little (if any) value in dental practice.

- The platelet function assay (PFA) test measures platelet dysfunction (adhesion and aggregation) with greater sensitivity and reproducibility than bleeding time. However, this test is nonspecific and should not be used for general screening purposes without knowledge of other variables that influence the test (e.g., complete blood count, von Willebrand factor levels)

- Tests to define specific platelet or clotting factor abnormalities generally should begin with general screening tests (e.g., platelet count, PT/INR, and aPTT) and then be confirmed with specific tests (e.g., bioassays of specific coagulation factors) by an internist or hematologist.

Specific Coagulopathies

Hemophilias

- The hemophilias are a group of inherited bleeding disorders in which one of the coagulation factors is deficient. The two most common are hemophilia A (Factor VIII deficiency) and B (Factor IX deficiency). Both are X-linked recessive diseases with a wide range of severity that correlates with factor levels.

- Severe disease is defined as less than 1% of normal factor activity, whereas 1% to 5% is moderate, and greater than 5% is mild.

Dental Considerations

- Bleeding may occur anywhere in patients with hemophilia. The most common sites are joints, muscles, and the gastrointestinal tract. With regard to the mouth, the likelihood of bleeding varies with the severity of the disease and the nature of the dental procedure.

- Approximately 25% of patients with severe hemophilia A and 3% to 5% of those with severe hemophilia B develop antibodies (primarily IgG) against the deficient factor. The presence of inhibitors may make the management of bleeding episodes more difficult. In hemophilia B, the development of inhibitors may be associated with some specific manifestations including anaphylaxis and nephrotic syndrome. Inhibitors are much less common in patients with mild or moderate disease.

- The decision regarding the need for blood products replacement for invasive dental procedures should be made with the physician managing the patient’s coagulopathy.

- Prevention of oral disease through frequent dental evaluation, fluoride use, strict oral hygiene, and diet control should be stressed to minimize later need for invasive dental procedures.

- Children should be seen starting in infancy to teach parents proper tooth brushing and to ensure adequate exposure to fluoridation.

- Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated in patients with hemophilia. Pain should be treated with acetaminophen or codeine.

- Moderate and mild hemophilia A can often be managed with the following:

- Desmopressin: Administered intravenously, by subcutaneous injection, or by intranasal spray. Transiently increases plasma levels of Factor VIII two to four times above the baseline via release from endothelial storage sites, and as much as four to six times above the baseline in those who begin with Factor VIII.

- Epsilon aminocaproic acid (EACA): Inhibits plasminogen activation in the fibrin clot and improves clot stability.

- Factors/dihydro-D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP) and routine local hemostatic measures (e.g., gelfoam and primary closure): These are helpful to maintain the clot.

- Patients with severe hemophilia A will often be given fresh frozen plasma or a Factor VIII concentrate (1 unit/kg of Factor VIII concentrate should raise the plasma level of the patient by 2%).

- In invasive procedures the goal is to raise the factor level to 25% to 50% transiently (the half-life of Factor VIII is about 12 hours). Surgical procedures, including extractions, might require raising the Factor VIII level to 100% with a presurgical bolus injection. This is often followed by 4 to 6 g epsilon aminocaproic acid four times daily for six to eight days, beginning six hours after the procedure.

- For less invasive procedures requiring infiltration or block anesthesia, the goal is to raise the plasma level to 15% to 20% transiently.

Hemophilia B

Treat either with Factor IX concentrate or with fresh frozen plasma.

von Willebrand Disease

von Willebrand disease (vWD) is an autosomal dominant disorder of platelet function and Factor VIII activity. It is the most common inherited bleeding disorder, affecting up to 1% of the population. It affects platelet plug formation during primary hemostasis and therefore many of its clinical manifestations are similar to those seen in platelet disorders (e.g., prolonged bleeding time, easy bruising).

Inherited von Willebrand disease has been classified into three types:

- Type 1, accounting for approximately 75% of patients, partial quantitative deficiency of von Willebrand factor

- Type 2, characterized by several qualitative abnormalities of von Willebrand factor. There are four subtypes: 2A, 2B, 2M, and 2N

- Type 3, the most severe form, characterized by a total deficiency of von Willebrand factor

- Patients with vWD tend to have a different pattern of bleeding from hemophilia.

- The treatment of vWD include: desmopressin, replacement therapy with von Willebrand factor-containing concentrates, anti-fibrinolytics, and topical therapy with thrombin or fibrin sealant. The majority of patients with mild or moderate Type 1 disease can be managed with desmopressin alone. Replacement therapy with VWF is usually required in Type 3 disease.

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count under 150,000/μl. It can be congenital, acquired, idiopathic, or secondary to medications or therapy. It is characterized by prolonged bleeding following surgery if platelet counts fall below 50,000/μl.

Dental Considerations

- Minimal trauma (e.g., toothbrushing, eating) can cause bleeding with counts below 20,000/μl.

- The most common presentation is mucosal or gingival bleeding. Large bullous hemorrhages may appear on the buccal mucosa due to the lack of blood vessel protection by the submucosal tissue. Cutaneous bleeding is manifested as petechiae or superficial ecchymoses.

- Unlike patients with coagulation disorders who experience delayed bleeding (several hours or days after trauma), patients with thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction tend to bleed immediately after vascular trauma.

Other Bleeding Disorders

There are many less common bleeding disorders (e.g., Glanzmann thrombasthenia, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome). The severity of the disease may be determined from the medical history. Additionally, it is important to consult with the patient’s physician or hematologist prior to scheduling an invasive procedure.

Medications That Predispose to Bleeding

Aspirin

Aspirin is commonly taken for its anti-inflammatory properties or prevention of coronary ischemic events. Because of its common use, patients might not list aspirin as a medication. There is longstanding dogma that aspirin or other antiplatelet drugs should be discontinued at least five days (the half life for platelets) prior to invasive dental procedures but there are no data to support this practice (including single tooth extraction). The American Heart Association published a statement warning clinicians about the risk of stopping antiplatelet drugs in patients taking them for coronary stents. Avoid aspirin in patients with pre-existing bleeding disorders.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are used for their anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic properties. Unlike aspirin, their anti-platelet action is reversible. NSAIDs should be avoided in patients with qualitative and quantitative platelet defects.

Thienopyridines

Thienopyridines (clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticlopidine) are antiplatelet agents used to prevent thrombotic events in patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or peripheral vascular disease. Normalization of platelet aggregation occurs five to seven days after discontinuation.

Warfarin

Warfarin is often used for maintenance anticoagulation therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation, atherosclerotic vascular disease, history of blood clot, CVA, prosthetic heart valves, and vascular grafts. Prolongation of PT/INR persists for three to four days after the last dose. INR level recommendations for invasive procedures are controversial; however, current literature indicates that moderately invasive surgery (e.g., single tooth extractions) is safe with an INR up to 4.0. Regional nerve blocks, such as the inferior alveolar nerve, should be done with caution. In general, the risk to the patient from altering the warfarin dosage far exceeds the potential problem of bleeding following a dental procedure.

Heparin

Heparin is generally used as an immediate anticoagulation, short-term treatment or a bridge to long-term anticoagulation with warfarin (e.g., for pulmonary embolus or deep venous thrombosis). It remains active five to six hours after the last IV dose. The use of low-molecular-weight heparin (e.g., Lovenox®) has become increasingly popular because of its more predictable pharmacodynamic effect and once-daily administration compared to unfractionated heparin. The elimination half life is about 4.5 hours after a single subcutaneous dose.

Thrombolytics

Thrombolytics (e.g., streptokinase, tissue plasminogen activator [tPA]), are fibrinolytic agents generally used for immediate thrombolytic treatment of stroke or life-threatening blood clot.

Drug Interactions

Broad-spectrum antibiotics used over an extended period may interfere with the intestinal flora and mucosal absorption. Corticosteroids, some antifungals, and oral hypoglycemics among other medications can interfere with INR levels in patients on warfarin.

Dental Considerations

- Consult with the patient’s physician if you are unsure about the impact of the anticoagulant(s) on surgical procedures.

- Infiltration anesthesia is preferred because blocks (e.g., inferior alveolar) could potentially cause bleeding in the pharyngeal space. Consider intraligamental and/or intrapulpal anesthesia for endodontic procedures and infiltration and/or intraligamental anesthesia for extraction procedures.

- Local hemostatic measures: Good surgical technique, pressure, and primary closure should be employed routinely in patients at risk for oral bleeding. The use of topical measures such as gelfoam, thrombin, and topical antifibrinolytics (e.g., epsilon-aminocaproic acid [EACA] rinse) may be used to control mild to moderate spontaneous oral bleeding.

- Exfoliation of primary teeth is generally not a concern because any oozing is usually well controlled by pressure.

Cancer

In cancer patients, the patient’s overall medical status and type of cancer therapy are of major concern. Cancer not only can cause significant morbidity, but can potentially lead to oral bacteremia and sepsis. Patients are at risk for developing oral complications throughout the course of cancer therapy and following cancer therapy due to late effects. Problems that arise are generally from two modes of medical therapy: radiation and chemotherapy.

Radiation Therapy to the Head and Neck Region

Although radiation therapy (RT) for most cancers has no discernible effect on the oral cavity or the provision of dental care, RT for the management of head and neck cancer, which may be delivered with concomitant chemotherapy, has a high incidence of oral sequelae.

Significant Elements in the Medical History for Patients Planned for RT

- Date of diagnosis

- Location and histology of the malignancy

- Tumor size, nodal involvement, and metastases (TNM) classification for staging head and neck tumors (Appendix 25, Table 25-2)

- Previous therapy (e.g., RT, chemotherapy, surgery, or a combination, or the use of radio-sensitizers)

Clinical and Radiographic Examination

- Location and size of tumor, if visible

- Status of soft tissues: Careful examination for oral lesions

- Teeth: Number, mobility, bone support, state of repair, caries, periapical or periodontal infection, impactions with or without potential for communication with the oral flora, gingivitis, periodontal disease

Dental Considerations for Patients Undergoing Radiation Therapy

Factors to consider prior to beginning invasive treatment, including restorative procedures:

- Overall tumor staging (TNM) and patient’s medical prognosis

- Field (i.e., the area receiving the highest dose), total dose, and fractionation (e.g., twice/day); external beam radiation (e.g., conventional RT, stereotactic RT, intensity-modulated RT) vs. interstitial implant (brachytherapy). Note: 6,000 cGy (centigray) = 60 Gy, where Gy is a unit of radiation called a gray, the standard unit of absorbed ionizing radiation dose, and represents 1 joule/kilogram

- The start date for RT

- Plans for radiation stents to decrease the dose to oral structures

- Plans for cancer chemotherapy prior to, during, or after RT

- Risk/benefit of maintaining each tooth: Often determined by location, degree, and potential for odontogenic infection (i.e., periodontal, pericoronitis, caries)

- Risk for developing oral problems as a result of radiation therapy. For example, mandibular teeth, especially molars, present a greater risk for osteoradionecrosis if extracted immediately before, during, or at any time after RT, and the risk of developing trismus and its impact on the ability to provide dental treatment

- Teeth with overall poor long-term prognosis, as well as those that are non-restorable, should be extracted as far in advance of RT as possible

- Periodontal disease: Teeth with greater than 4-mm pockets should be considered for extraction, especially mandibular posterior teeth if the mandible is in the RT portal

- Dental caries: Generally, if shallow, these can be restored before or soon after RT. If the caries are of moderate depth, ensure pulp vitality and restore before RT, or at least use an intermediate restorative material until more definitive restorations can be accomplished

- Status of salivary gland function following radiotherapy. Parotid gland tissue, if in the radiation field, will usually recover from less than 3,000 cGy but can remain non-functional from greater than 5,000 cGy

- Preventive oral care: It is important to educate patients about their increased risk for dental caries (especially in patients at risk for hyposalivation). A preventive oral health care program (e.g., use of fluoride, noncariogenic diet, more frequent dental visits) should be instituted as early as possible.

Major Oral Complications of Radiation

Mucositis

- Mucositis refers to inflammation of the oral mucosa from RT, which can progress to ulcerations. Mucositis is usually short-term, but in severe cases it can limit the RT dose and interrupt the schedule of radiation. Management includes:

- Maintaining oral hygiene throughout therapy

- Bland rinses to debride the mouth, especially in the absence of saliva

- Altering the oral intake to softer/blander foods at the earliest signs or symptoms to prevent pain or damage to friable mucosa

- Topical anesthetic rinses may be helpful for mild to moderately painful mucositis (Appendix 12, Table A12-4). There are many single and combined preparations

- Topical anesthetics should be used with caution in young children due to their inability to expectorate and their higher risk for overdosage and toxicity

- Systemic analgesics or opioids are necessary for more severe pain. NSAIDs or synthetic opioids should be tried first, with escalation to stronger opioids as necessary. Topical therapies may play an important role as an adjunct to systemic pain control

- When nutrition is significantly compromised, surgical placement of a gastric feeding tube may be required to maintain nutrition and avoid breaks in RT

Xerostomia

Radiation to the head and neck can cause both acute and long-term salivary gland hypofunction, leading to xerostomia; difficulty speaking, eating, and swallowing; and an increased rate of dental caries and candidiasis. Intensity modulated radiation therapy is reported to reduce the incidence and severity of salivary gland damage. Although infrequently used, amifostine, which acts as a free radical scavenger delivered intravenously or subcutaneously, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of radiation-induced salivary gland hypofunction.

- Xerostomia can be palliated by the use of oral moisturizing rinses, saliva substitutes, or water (including ice chips).

- Pilocarpine hydrochloride may help to increase salivation and decrease xerostomia in some patients, especially for persistent xerostomia following completion of therapy. The main side effect is excessive sweating.

- Cevimeline, which has been approved for Sjögren’s disease, also may be used. As with pilocarpine, the side effects include sweating and gastrointestinal symptoms (Appendix 6, Table A6-5).

Radiation Caries

Radiotherapy damage to the salivary glands and subsequent dry mouth may drop saliva production to less than 5% of normal. Protective immunoglobulin A and the buffering and remineralizing capacity of saliva are lost, with a resultant salivary pH that can drop below 3.5.

- Patients need dietary counseling along with routine and careful follow-up for as long as the mouth continues to have any degree of dryness, with or without an increased incidence of caries.

- Use of extra-strength fluoride toothpaste is very important.

- A neutral sodium fluoride rinse or brush-on fluoride gel should be used every evening after careful tooth brushing and flossing (Appendix 24, Table A24-2).

- Other adjunct therapies include use of casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate agents (e.g., MI Paste™ MI Paste, Recaldent™) and xylitol-sweetened products.

- The diet should be modified to avoid refined carbohydrates, especially sucrose, and acidic foods and beverages (e.g., iced tea).

Infection

Bacterial

Gingival organisms might not survive during RT but bacterial and fungal pathogens may increase as a result of RT on the mucosa, decreased oral hygiene, increased cariogenic diet and dry mouth.

Fungal

Both pseudomembranous and erythematous candidiasis is common. Fungal infections are often long-lasting and can recur. Management includes topical and/or systemic antifungal agents, and any removable oral appliances must be disinfected nightly (e.g., with dilute bleach solution or Peridex®) (Appendix 12, Table A12-4).

- Clotrimazole troches are given at the onset of infection and continue for the duration of RT. Dissolve clotrimazole troches in water if xerostomia prevents them from dissolving in the mouth. Miconazole is an alternative; some topical preparations may contain high levels of sucrose as a flavoring agent.

- Fluconazole is the usual first line therapy when systemic antifungal medication is required. This medication is dosed once daily and is typically more effective than topical agents and therefore should be considered in cases of refractory infection or in patients in whom compliance with complex daily regimens is a concern.

Osteoradionecrosis

Osteoradionecrosis is characterized by exposed alveolar bone, and is most likely to occur with greater than 60 Gy to the mandible, although the maxilla also can be involved. It is caused by permanent damage to the bone and blood supply, and can occur spontaneously or after an invasive procedure exposing alveolar bone.

Dental Considerations

- Secondary soft tissue infection is common and may require long-term courses of topical and systemic antibiotics.

- Some advanced or longstanding (greater than 6 months) cases may require surgical management, with or without the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

- Invasive dental procedures (e.g., extractions) are best completed prior to RT, with at least one to two weeks for healing.

- Following RT, teeth requiring extraction should be removed as atraumatically as possible, with careful alveoloplasty, primary closure of the mucosa if possible to help maintain the clot, and short-term antibiotic coverage.

Taste Loss/Dysgeusia

Taste loss/dysgeusia is a common problem when the tongue is in the RT field. It usually resolves completely, and the greatest resolution occurs within three months of treatment. Persistent changes at one year are typically permanent.

Trismus

Trismus can arise from radiation, surgery, or a combination of both. It is more common with tumor primary sites in the nasopharyngeal or tonsil region. Soft tissue fibrosis of the tissues surrounding the temporomandibular joint typically develops three to six months after RT and can be progressive.

Dental Considerations

- Oral hygiene practices, speech, nutritional intake, and dental treatment are often challenging for these patients, depending on the degree of trismus. Management requires intensive physical therapy with passive mouth opening exercises or with a device designed for this purpose.

- Some evidence suggests a benefit of exercise that begins during RT.

Tooth and Bone Development

RT has an impact on the developing teeth and on active growth areas of the mandible. Direct, high-dose RT to the dentoalveolar complex during early phases of tooth development may destroy odontogenic precursor cells and result in complete agenesis of the tooth. Radiation at a later stage of dental development or at a lower doses results in more minor defects ranging from microdontia, enamel hypoplasia, incomplete calcification to arrested root development.

Chemotherapy

The major concerns with dental management and chemotherapy are related to direct and/or indirect toxicity to the oral mucosa from cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. The pathobiology for chemotherapy-related toxicity to the oral mucosa is complex and not fully understood. It involves damage to both DNA and non-DNA targets, and generation of messenger signals, leading to the production of a variety of biologically active proteins, including proinflammatory cytokines that damage surrounding tissues. The extent and severity of mucositis are influenced by the specific chemotherapy drug (i.e., stomatotoxicity); dose, route, and frequency of administration; and individual patient tolerance (Appendix 12, Table A12-3).

Significance of the Problem

- Mucositis, which affects upwards of 35% of patients, is typically a short-term, self-limiting effect of chemotherapy that can extend from the mouth through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

- Other potential consequences include infection of oral mucosa, gingival bleeding, and impaired nutrition.

- Mucositis and infection, along with other mucosal toxicities and bacteremia, in particular alpha hemolytic streptococcal from ulcerative mucosa during myelosuppression, are common problems. Thinned mucosa and ulceration also allow for fungi and viruses to invade local tissues and the circulation.

- Symptoms include painful mucosal inflammation that can extend to limited or extensive ulcerations, severe pain, dysphagia, and an inability to tolerate any oral intake.

Significant Elements in the History

When assessing a patient receiving cancer chemotherapy, consider:

- Tissue diagnosis, prognosis, and chemotherapy regimen

- Overall status, including nutrition, current blood counts, debilitation, ability to tolerate dental treatment

Dental Considerations

- Timing and type of chemotherapy: In general, if within the previous three weeks, the oral mucosa and bone marrow may be compromised; the extent is largely dependent on the chemotherapy regimen. Chemotherapy regimens for bone marrow malignancies and conditioning regimens prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are generally more myeloablative compared to those for solid organ neoplasms (e.g., head and neck squamous cell carcinoma) and patients in the former group are at high risk for infectious complications during the period of pancytopenia which typically begins seven to fourteen days after chemotherapy is delivered.

- Cancer patients benefit from a comprehensive oral examination before the initiation of cancer therapies, especially if they are to receive radiation treatments to the maxillofacial region or intensive chemotherapy protocols. Comprehensive preventive oral care appears to diminish the incidence of all oral complications of chemotherapy, but data are lacking.

- Pre-chemotherapy oral hygiene protocols may include root planing and scaling, moderate to deep caries treatment, extractions, and in rare situations, endodontic therapy.

- Gingivitis and periodontal disease involve bacterial plaque adjacent to assumed ulceration in the periodontal pocket and this should be considered a focus of infection in febrile neutropenic patients.

- Blood counts. Exercise caution if the patient has:

- A total white blood cell count less than 2,000/mcL, and more importantly, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) less than 500/mcL. The duration of neutropenia is the greatest risk factor for infection.

- Platelets less than 50,000/mcL. If contemplating surgery prolonged mucosal/gingival bleeding is unlikely with a platelet count greater than 25,000/mcL.

- Pre-chemotherapy oral disease such as gingivitis, periodontitis, and periapical disease are thought to increase the risk for mucositis, local infection, and bacteremia from oral pathogens.

- Younger patients may have a greater risk of chemotherapy-induced stomatitis, perhaps related to a higher epithelial mitotic rate and the nature of malignancies being treated (e.g., leukemias).

- Nutritional status, type of malignancy, duration of neutropenia, and the quality of oral care are also thought to influence the severity of mucositis.

- Surgical procedures:

Pretherapy tooth extractions do not pose significant risk of postextraction complications, but they should be done as far from a period of significant neutropenia as possible because re-epithelialization and general healing of the socket and alveolar bone slows or stops during chemotherapy.- Attempt to get primary closure of the wound. The use of hemostatic packing agents is controversial.

- Consider platelet transfusion one-half hour pre-procedure if the platelet count is under 30,000 to 40,000/mcL.

- Consider antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., clindamycin 600 mg) for tooth extractions that must be done during severe neutropenia (ANC less than 500/mcL).

- Risk of complications from dental treatment: The indication for dental treatment depends on the urgency. Sequelae from postponed treatment also must be considered. For uncomplicated post-surgical healing to occur platelet counts should be maintained above 20,000/mcL for anticipated clot turnover for the following week. The ANC should ideally be maintained at greater than 1,000/mcL for seven to 10 days. Patients might have a coagulopathy from their disease (e.g., leukemia with poor platelet function) as well as from treatment (myelosuppression following chemotherapy).

Prevention of Oral Complications

Preventing and minimizing oral complications during chemotherapy is the goal. Prior to chemotherapy, if the systemic condition allows and there is sufficient time before severe myelosuppressive effects occur, the following measures should be taken:

- Thorough oral examination, including a full-mouth series of radiographs

- Extract hopeless periodontally or cariously involved teeth

- Thorough oral prophylaxis and oral hygiene instruction. Patients should be educated about the relationship between odontogenic disease and problems during chemotherapy

- Orthodontic appliances are almost always removed when intensive chemotherapy is planned, given the potential for gingival inflammation, problems with oral hygiene, and risk of soft tissue injury

- Removable prostheses and appliances generally should be left out of the mouth during periods of neutropenia or thrombocytopenia

- Fluoride: Neutral rinse if the patient can tolerate it or fluoride gel is recommended by some oral care protocols, especially with xerostomia and the desire to arrest carious lesions. Discontinue if mucosal burning sensation occurs. Dose and timing is important with regard to other oral care, such as mouth care, topical anesthetics, and antifungals, so as not to interfere with the benefit of each. For example, mouth care should be done first. Topical anesthetics and antifungals should not be followed by other oral medication or rinses until sufficient time for their efficacy has abated

- Standard oral hygiene (brushing and flossing) should be maintained throughout chemotherapy unless there is gingival bleeding. It is generally felt that the risk of worsening gingival disease (and the resultant increase in potential for bacteremia) is greater than the risk of bacteremia from oral hygiene procedures. In such cases, patients can rinse with sterile saline or bicarbonate or even plain water to debride the mouth and reduce plaque and debris accumulations. Commercial mouthwashes often contain alcohol and can sting ulcerated mucosa, and should therefore be avoided

- Chlorhexidine mouth rinses may be considered in patients with periodontal disease

- Xerostomia is less common with chemotherapy compared to radiotherapy. It can result from anticholinergic medications given for nausea or diarrhea. Some patients note excessive saliva and some experience thick, ropy saliva. Patients also may complain of dysgeusia. Xerostomia in this setting is almost always reversible after chemotherapy and has no significant long-term effects. Therapy is symptomatic (e.g., frequent rinsing with bland, non-cariogenic solutions)

Infection

- During neutropenia, signs and symptoms of infection (e.g., reduces swelling, pain, pus formation) may be muted.

- During severe neutropenia (ANC below 500/mcL), manage with broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics. Consider covering Gram-negatives and anaerobes (e.g., Bacteroides sp., Escherichia coli, Serratia, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella spp.) in addition to the usual Gram-positive oral flora. Elective dental procedures should wait until the ANC rises to more than 1,000/ mcL and platelets to greater than 50,000/mcL.

- For superficial candidiasis provide topical treatment with clotrimazole troches (Appendix 12, Table A12-4). If extensive, or if WBC counts are low, oral or parenteral fluconazole or parenteral amphotericin B may be needed. Some recommend prophylactic oral fluconazole to decrease the incidence of candidiasis but the efficacy is unclear.

- For viral pathogens, the most common is reactivation of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 infection, which tends to be more severe and of longer duration than non-HSV-associated mucositis. The typical vesicular lesions may not be evident in the presence of chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Infection with HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with mucosal vesicles or unusually painful oral ulcerations after chemotherapy.

Mucositis Pain

- Begin with frequent rinses with a bland solution (e.g., baking soda and water) and progress to one of several topical anesthetics (Appendix 12, Table A12-4) with or without lidocaine in equal parts. Morphine mouth rinses may have better efficacy than the standard agents such as lidocaine. Various combinations of an anti-inflammatory, a topical analgesic and/or coating agent (e.g., Kaopectate®) are used. Change to systemic opioids if ineffective. The use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) has been found to be beneficial in pain alleviation in adult and pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.

Bleeding

Gingival bleeding is not uncommon with low platelet counts, especially when prolonged and in the presence of periodontal diseases and associated gingival ulceration. This is usually prevented with good oral hygiene. If brushing and flossing create pain or bleeding, chlorhexidine oral rinses will help to control plaque formation.

- Bleeding usually occurs from the gingival crevice with a very low platelet count (less than 15,000 to 20,000/mcL). If pressure from a wet 2-cm × 2-cm sponge fails to stop the bleeding, a topical thrombin-soaked sponge may be applied to the area and held in place for one to two minutes. Remove the sponge gently so as not to disturb the new clot. There is a degree of concern over the use of topical thrombin because of sensitivity and this should be discussed with the patient’s physician. Avoid any gingival manipulation (e.g., brushing) within 48 to 72 hours of oral bleeding or until the platelet count shows a steady increase.

Nutrition

Weight loss can be a temporary side effect of a sore or dry mouth or throat, nausea/vomiting, poor appetite, diarrhea, or dehydration. Consult with a dietitian. A soft and/or liquid diet (e.g., ice cream and watermelon) may be helpful. Avoid tart or acidic foods (e.g., citrus juices and fruits, seasoning and spices), alcohol, cigarettes, and very hot or cold foods. Sugarless candy or mints can stimulate saliva production, although sharp edges may injure the oral mucosa.

Tooth and Bone Development

Chemotherapy targets rapidly dividing cells throughout the body; therefore, cells that are in non-proliferative germinal stage (e.g., second and third molars in an infant) develop normally and remain unaffected by chemotherapy. Most dental defects from chemotherapy are localized and complete tooth agenesis is rare.

Osteonecrosis from Intravenous Bisphosphonate Therapy

Bisphosphonates are given to inhibit osteoclastic activity (Appendix 12, Table A12-2). The intravenous route is used in clinical practice for the management of cancer-related conditions such as bone metastases from breast, prostate, and lung cancer and management of lytic lesions due to multiple myeloma. Since it was first reported, the term bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) has been adopted for this condition. It is defined as exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than eight weeks, in the absence of radiation therapy to the jaws (Appendix 25, Table A25-1). Risk factors for the development of BRONJ are:

- Intravenous route of administration; longer duration is associated with increased risk

- Local factors including dento-alveolar procedures, anatomy, and presence of oral disease

Dental Considerations for Cancer Patients Undergoing Intravenous Bisphosphonate Therapy

The dental evaluation for patients exposed to intravenous (IV) bisphosphonates is similar to patients undergoing radiation therapy. Factors to consider include the following:

- Cancer diagnosis and patient’s overall prognosis

- Type, duration, and route of administration of bisphosphonate therapy

- Risk/benefit of maintaining each tooth: Location, degree, and potential for odontogenic infection (i.e., periodontal, pericoronitis, caries)

- It is unclear at this time if patients are more at risk from a dental extraction than from leaving in place a broken down but not obviously infected tooth

- Exercise caution with all dental procedures to keep trauma to soft tissues at a minimum, and avoid exposing bone whenever possible

Cardiovascular Disorders

Significance of the Problem

There are a large number and nature of cardiac conditions of concern to dentists. Some require no change in dental management and others may put patients at considerable risk for dental procedures. In general, if unsure about the patient’s cardiac condition, consult the patient’s primary care physician or cardiologist for details before dental treatment. Decisions on management rest with the treating dentist, who takes ultimate responsibility for issues such as antibiotic prophylaxis (Appendix 23, Table A23-1).

Considerations Concerning Bacteremia

The oral cavity, and the gingival crevice/periodontal pocket in particular, have a large and varied potential population of bacterial species, and bacteremia from this site is common. However, there are little scientific data to suggest that invasive dental procedures are a significant cause of distant site infection (e.g., infective endocarditis), given that far more frequent bacteremia occurs from naturally occurring sources such as tooth brushing and chewing food. Consider that:

- Any manipulation of the gingiva can cause a bacteremia, and a single dental extraction may have a bacteremia incidence of over 90%.

- Routine cleaning (scaling) of teeth is as likely as, or more “invasive,” than an extraction with respect to causing bacteremia.

- The incidence (and perhaps magnitude) of bacteremia likely increases with the number of teeth extracted. The usual duration of a bacteremia ranges between 10 minutes to more than an hour. The duration is likely dependent on host immunity and other factors and the volume of organisms entering the circulation. Pre-surgical antibacterial mouth rinses may have little if any effect on the incidence of bacteremia.

- Systemic antibiotics alter the nature and reduce the incidence and duration of a bacteremia, but it is not clear to what extent they reduce the risk of distant site infections (e.g., infective endocarditis).

Infective Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the myocardium (usually a valve) of the heart by circulating pathogenic organisms.

Congenital Heart Disease

Congenital cardiovascular malformations can be cyanotic (dominant right-to-left shunting), non-cyanotic (dominant left-to-right shunting) or without shunting. Cyanotic defects include tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great vessels, anomalies of the tricuspid valve, pulmonary atresia, pulmonary stenosis, Eisenmenger’s syndrome, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome (aortic atresia). Surgical correction of these defects is often accomplished in infancy and early childhood. Non-cyanotic defects include ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), patent ductus arteriosus, coarctation of the aorta, aortic valve stenosis, and mitral valve prolapse.

Cardiac/Vascular Prostheses

Prosthetic heart valves are either mechanical (man-made materials, usually carbon alloys) or biological/porcine. Mechanical valves are placed in about 60% of patients and they typically require life-long anticoagulation therapy, most commonly with warfarin.

Dental Considerations

- Congenital cardiac defects are associated with many syndromes (including Down syndrome), inborn errors of metabolism, and connective tissue disorders (e.g., Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, lupus erythematosus). A careful cardiac history should be taken for these patients.

- 2007 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend antibiotic prophylaxis in the following four groups of cardiac patients given their higher risk of IE with bad outcome (Appendix 21, Table A21-1):

- History of IE

- History of heart transplant with an associated new valvular lesion

- History of unrepaired congenital cyanotic heart disease

- Prosthetic valve

- Rheumatic heart disease and other conditions such as mitral valve prolapse (MVP) put people at risk for infective endocarditis but the data to suggest these people benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures is lacking. AHA guidelines do not recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for any dental procedures for this “moderate risk” group of patients.

- Appropriate laboratory tests for patients taking warfarin is an INR. Rarely, the warfarin dose might need to be adjusted to bring the INR within a safe range for dental procedures, usually less than 4.0. The risks of decreasing the INR (e.g., stroke, thrombosis) greatly outweigh any risk of prolonged bleeding from extractions and other invasive procedures.

Cardiac Pacemaker and Nonvalvular Cardiovascular Devices

Implanted devices, such as cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), are increasingly important in the management of heart failure and the prevention of sudden death from arrhythmias.

Dental Considerations

- The risk of ICD infection from a dental procedure is very low or nonexistent. The AHA does not recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with nonvalvular cardiovascular devices undergoing dental procedures because of lack of evidence to suggest increased risk of device infection.

- Use of certain electronic dental devices, including ultrasonic scalers, electric pulp testers and electrosurgery units, and battery-operated composite curing lights, should be avoided because of possible interference with pacemaker function, at least in vitro.

Myocardial Infarction

Significance of the Problem

- Patients with myocardial infarction (MI) may have low cardiac output and/or arrhythmia (e.g., atrial fibrillation).

The major concern is prevention of additional infarction and heart muscle damage.

Dental Considerations

- MI within past six months: Clinical dogma and textbooks suggest that elective procedures should be avoided during this period, but this is based on data that more MIs occur during surgery under general anesthesia. Data are not available concerning the risk of outpatient dental treatment.

- MI more than six months ago: For stressful dental procedures, it is advisable to consult the patient’s physician concerning coronary vessel and myocardial involvement, previous coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), arrhythmias, medications, the presence of other vascular disease, and whether or not the patient has a pacemaker or defibrillator.

- The patient may be on warfarin or aspirin therapy for anticoagulation. The INR (if on warfarin) should be less than 3.5 to 4.0 for invasive procedures.

- Avoid long and/or stressful procedures; multiple short appointments may be preferable unless the patient has to travel long distances. Be cautious if using epinephrine as a vasoconstrictor in local anesthetic. Consider nitrous oxide.

- Be aware that gingival hyperplasia can occur with calcium channel blockers.

- Although there is likely an association between periodontal disease and atherosclerosis, independent of common risk factors (e.g., smoking), a causal link has not been established.

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG)

Reestablishment of blood flow to blocked coronary vessels is important, if it can be done within hours of an MI to prevent ischemia and cardiac muscle cell death.

Dental Considerations

- The major concern for dentists is myocardial infarction. Consult the patient’s physician, asking the questions outlined in the MI section above.

- Although some clinicians allow the same six-month delay before resuming dental treatment following CABG surgery as for patients with a history of MI, there is no well documented need to wait longer than six weeks.

- There is no evidence of a risk of infection of grafted coronary vessels from dental procedures.

Angina

Angina occurs when myocardial oxygen demand exceeds supply.

Dental Considerations

- The major concern is to reduce the possibility of an anginal attack. Ask the patient:

- Does angina occur at rest?

- What are the precipitating factors (e.g., exercise, stairs, emotional stress), frequency, duration, timing, severity of attacks, and response to medication?

- Do you have a coronary stent? Patients may be on antithrombotic therapy with antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant drugs.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided.

- Elective treatment is reasonable if the angina is stable and well controlled by one to two nitroglycerin tablets, and if episodes are less frequent than one per week. Avoid elective treatment if these limits are exceeded because the angina is considered unstable. Crescendo (increasing frequency) angina patients are at high risk for MI. Consult the patient’s physician before treatment.

- Assess vital signs at each appointment.

- Many patients with angina are on one or more of the following drugs: nitrates, beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers.

- Side effects from beta blockers include bradycardia, conduction disturbances, and fatigue.

- Side effects from calcium channel blockers include bradycardia, worsening heart failure, headache, and dizziness.

- The patient’s nitroglycerin tablets or spray should be readily available during the procedure. If attacks are more than one per week, or if the patient is fearful and non-elective care is planned, consider nitroglycerin use at the start of the appointment.

- Consult the patient’s physician when considering sedation or with questions concerning anticoagulation, exercise tolerance, or risk from invasive/stressful procedures.

- Do not stop antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy for dental procedures.

- Respiratory depressants such as opioids, barbiturates, and other sedatives can worsen the cardiovascular status.

- Nitrous oxide/oxygen relative analgesia can be used safely in cardiac patients, but the oxygen content should not drop below 35%.

- Use of local anesthetics with vasoconstrictors is controversial with some cardiac defects. The benefits of vasoconstrictors (e.g., more profound and longer anesthetic effect) probably outweigh the risks in most cases, but restricted outflow track defects (e.g., aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) are an exception. Avoid concentrations of epinephrine greater than 1:100,000 parts epinephrine and restrict the total volume of local anesthetics.

- Consider short appointments.

- For restorative treatment on elderly patients, particularly in teeth with existing restorations, pulpal discomfort is likely to be minimal and anesthetic may not be necessary. This should be discussed with the patient in advance.

Congestive Heart Failure

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a common and complex clinical syndrome caused by a variety of cardiac diseases that have a common origin in any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood. It is important to understand the status and stages of the CHF.

Classification

The New York Heart Association classification assigns patients to one of four functional classes, depending on the degree of effort needed to elicit symptoms (Appendix 6, Table A6-3):

- Class I: Symptoms of HF only at activity levels that would limit normal individuals

- Class II: Symptoms of HF with ordinary exertion

- Class III: Symptoms of HF with less than ordinary exertion

- Class IV: Symptoms of HF at rest

Significant Elements in the History

- Patients often have a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) and variable levels of compensation, and might be on multiple medications and dietary measures to control and balance cardiac function (Appendix 6, Table A6-3).

Dental Considerations

- If well compensated, patients can undergo elective dental treatment. If not, stressful treatment should be deferred until the patient is stable. Signs of poor compensation include:

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND): Patient awakens at night short of breath as a result of pulmonary congestion

- Orthopnea: Patient might have to sleep with two or more pillows to prevent pulmonary fluid congestion. Patients with orthopnea probably have a low tolerance for the supine position in the dental chair. Consider conducting dental treatment with the patient in the upright or semi-upright position as tolerated

- Shortness of breath (SOB) or dyspnea on exertion (DOE): Ask how many steps or flights of stairs the patient can climb without having to stop and rest

- Pedal edema: Results from right heart failure. Question the patient about swollen ankles and examine for a depression left after pressing a swollen ankle with a finger (pitting edema).

- Body weight: Can fluctuate by a pound or more per day. It is used as an indicator of therapeutic measures and reflects changes in body water.

- Because patients can have orthostatic hypotension (as a result of medication), raise them to a sitting position in several stages over several minutes. Ask them to sit with their feet on floor for 2 minutes before standing upright.

- Patients might have urinary urgency during morning appointments in response to a diuretic. Ask if they would like to use the bathroom before the procedure.

Heart Transplantation

The major concerns are life-long immunosuppression and current cardiac status.

Dental Considerations

- The impact of immune suppression on oral infection and risk for distant site infection from the mouth are unclear. Immunosuppression focuses on lymphocytes, and is at a higher level in the first six months following transplant, after which it is reduced to a lower level.

- Bacterial endocarditis is a concern, as valve damage might follow catheterization for heart muscle biopsy (for evidence of rejection). Consider using prophylactic antibiotics for invasive procedures as per AHA guidelines (Appendix 23, Table A23-1).

- Oral complications include xerostomia, oral candidiasis (secondary to steroids use) and cyclosporin-induced gingival hyperplasia.

- Patients may be anticoagulated with warfarin and should be tested for INR and evaluated as per patients following MI.

- Patients might be best managed by having dental treatment after cardiac transplantation, depending on their overall status and the nature of the indicated dental treatment. A severely compromised patient in cardiac failure is likely at greater risk from dental treatment of any kind before transplantation, in spite of the concern for post-transplant immunosuppression.

- Avoid elective treatment with less stable patients and during a rejection episode.

Cerebrovascular Accident

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA; stroke) presents in a variety of ways, including but not limited to headache, nausea and vomiting, numbness, weakness or paralysis of one side of the body or the face, confusion, and aphasia (inability to speak) (Appendix 5). A transient ischemic attack (TIA) might be a warning of an impending CVA and therefore requires urgent assessment.

Dental Considerations

- CVA generally fall into two distinct categories with occasional overlap:

- Ischemia, which is characterized by diminished and inadequate blood flow to the brain. This is caused by:

a. Thrombus: in situ clot in a small or large artery caused by atherosclerosis or other intravascular injuryb. Embolus: A clot that is formed elsewhere and travels to the small or large arteries of the brain. This is often seen in patients with atrial fibrillation

- Hemorrhage, which is characterized by bleeding within or surrounding the brain. This is caused by:

a. Intracerebral hemorrhage: Most commonly small vessel bleeding directly into the brain parenchymab. Subarachnoid hemorrhage: Most commonly ruptured aneurysm that bleeds into the CSF

- Ischemia, which is characterized by diminished and inadequate blood flow to the brain. This is caused by:

- Both the onset and extent of the symptoms depend on the severity of the event, whether ischemic or hemorrhagic.

- Patients with a history of CVA might be on anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, aspirin). An INR test, in the case of warfarin, is necessary to evaluate the risk of bleeding from invasive dental procedures.

Arrhythmias

Arrhythmia is defined as any cardiac rhythm that does not originate in the sinus node and follow normal atrioventricular conduction pathways. There is a wide variety of arrhythmias, some of which are of significant concern for dental procedures.

Significant Elements in the History

- What is the nature of the arrhythmia?

- Is the arrhythmia symptomatic? The following require medical attention:

- Syncope or near syncope

- Sustained periods of irregular rhythm

- Does the arrhythmia pose a risk to the patient in the dental office setting?

- Is the patient anticoagulated?

- Does the patient have an implanted device such as pacemaker or defibrillator?

Dental Considerations

- Patients with atrial fibrillation as well as some other arrhythmias are often anticoagulated with an increased risk for bleeding from dental procedures.

- Epinephrine in local anesthetics is not recommended and patients should be monitored during dental procedures.

- Consult with the patient’s physician.

- See above for considerations in patients with implantable cardiovascular devices.

Hypertension

Significance of the Problem

- Hypertension is a very common medical condition. Upwards of 29% of Americans, about 58 million to 65 million people, are estimated to have the condition.

- Only about 50% have their blood pressure under control.

- Hypertension is also a problem of childhood, but routine blood pressure measurement for children has a low yield for undiagnosed hypertension.

Classification

See Appendix 6, Table A6-4. The definition is based upon the average of two or more properly measured readings at each of two or more visits after an initial screen.

- Normal blood pressure: Systolic under 120 mmHg and diastolic under 80 mmHg

- Prehypertension: Systolic 120 to 139 mmHg or diastolic 80 to 89 mmHg

- Hypertension: Stage 1: Systolic 140 to 159 mmHg or diastolic 90 to 99 mmHg

- Hypertensive urgency: Asymptomatic patients with diastolic greater than 120 mmHg without evidence of end-organ damage

- Hypertensive emergency/malignant hypertension: Severe hypertension with systolic usually greater than 180 mmHg with evidence of end-organ damage (e.g., CNS: retinal hemorrhage, exudates, papilledema, headache, CVA; Cardiac: MI, CHF; Renal: proteinuria)

Dental Considerations

- The major concern is precipitating a hypertensive crisis, stroke, or MI.

- Patients often show poor compliance with blood pressure medications and diet. They need reinforcement concerning the importance of medications in preventing cardiovascular problems.

- Side effects of antihypertensives vary and can include orthostatic hypotension, synergistic activity with narcotics, and potassium depletion. Beta blockers will decrease the response to medications (e.g., epinephrine) used to treat anaphylaxis.

- The use of epinephrine in patients with hypertension is controversial. However, the benefit from prolonged and more profound anesthesia is thought to outweigh the risk of systemic effects (e.g., acute increase in blood pressure or arrhythmia). Do not use concentrations greater than 1:100,000 parts epinephrine. Aspirate the syringe prior to injection and avoid intravascular injection.

- Poorly controlled or uncontrolled patients should not have a stressful dental procedure until their hypertension is under control. Elective treatment also should be avoided if the blood pressure is significantly above the patient’s baseline or if it is greater than 180 mmHg systolic or greater than 100 mmHg diastolic.

- Patients in pain may have some lowering of their pressures after local anesthesia.

- Monitor the blood pressure before, during, and after treatment.

Diabetes Mellitus

Significance of the Problem

- The estimated prevalence of diabetes among adults in the United States ranges from 4.4% to 17.9%.

- Microvascular and macrovascular disease result in complications such as myocardial infarction, stroke, end-stage renal disease, retinopathy, and foot ulcers.

- Good glycemic control decreases the risk of progression of complications of micro- and macrovascular disease.

- Diabetics are at increased risk of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease (CAD) compared to non-diabetics. In addition, they are more likely to have atypical symptoms of angina and myocardial infarction (MI).

- Prevention of cardiovascular morbidity is a major priority; this is achieved through aggressive medical management of blood glucose as well as other risk factors such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia.

- Blood pressure and cholesterol level goals are lower in diabetics than in nondiabetics.

- Hypoglycemia is a life-threatening risk of aggressive blood glucose control and should be carefully monitored.

Classification

- Type 1 (formerly insulin-dependent or juvenile onset): Patients produce little or no insulin. This type accounts for about 10% of all diabetics. There is a greater tendency to ketoacidosis than with Type 2. Most children with diabetes have Type 1 and have a lifelong dependency on exogenous insulin. Causes: autoimmune, idiopathic

- Type 2 (formerly non-insulin-dependent or adult onset): Non-ketosis-prone diabetes. Insulin receptors display diminished sensitivity to insulin. Causes: genetic predisposition, obesity

- In type 2 diabetes, disease onset is insidious

- Gestational diabetes: Onset of impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy, usually returns to normal after childbirth, with increased risk of developing diabetes within five to 10 years

Hyperglycemia

- Can occur as a result of an infection, MI, stroke, weight gain, pregnancy, hyperthyroidism, steroids, fever, dehydration or non-compliance with medical care.

- Signs include flushed face, dry skin, dry mouth, weakness, dehydration, Kussmaul (very deep and rapid) respirations, elevated pulse, decreased blood pressure, and lethargy.

- Patient can show polydipsia, polyphagia, and polyuria (the “polys”); there might also be abdominal pain, nausea, or unconsciousness. Can result in diabetic coma, with the patient in a hyperosmolar state.

- Hyperglycemia can progress to ketoacidosis and coma over several hours or days in patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Early recognition is important. Give basic life support if indicated. Get immediate medical assistance.

Hypoglycemia: Insulin Shock

- Loss of consciousness occurs rapidly if the blood glucose falls to below 50 mg/100 cc. Common causes of hypoglycemia are omission or delay of meals, excessive exercise prior to meals, overdose of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, and stress.

- It usually appears first as decreased cerebral function, mental confusion, headache, dizziness, changes in mood, hunger, nausea, and increased epinephrine activity (sweating, tachycardia, piloerection, increased anxiety) as an endogenous reaction to raise blood glucose.

- The patient may appear intoxicated and might progress rapidly to unconsciousness, convulsions, and coma.

Treatment

- Early recognition

- Give the patient oral or parenteral simple carbohydrates (e.g., orange juice, soda, sugar)

- Get immediate medical assistance

- Provide basic life support

Significant Elements in the History

- Age of onset

- Control of glucose levels

- Compliance with medical management

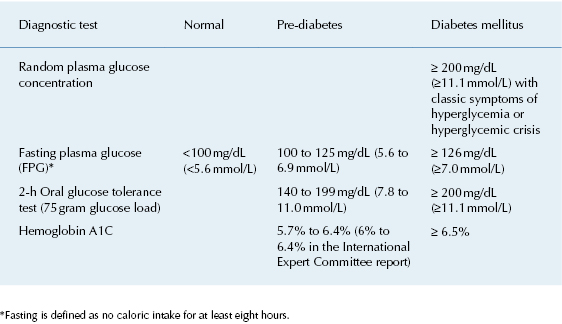

- Hemoglobin A1C level (Table 2.1)

- Symptoms: Excessive thirst, nocturia, malaise, decreased appetite, nausea/vomiting, hyperpnea

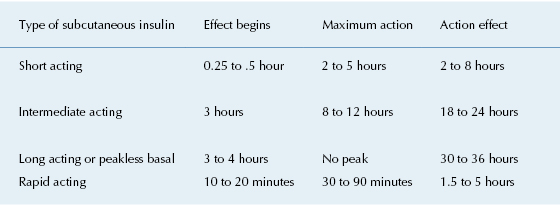

- Treatment: Make a note of the patient’s diet, insulin dosage, route, frequency, and timing of injection. The type of insulin should be noted (Table 2.2). Some patients might use an insulin pump to deliver steady doses of insulin

- Hospital admissions: Record admissions for uncontrolled state (e.g., insulin reactions, diabetic coma)

- Other complications of diabetes: Retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy, gastroparesis

Table 2.1. Screening Tests for Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus

Table 2.2. Types and Durations of Insulin Therapy

Dental Considerations

General

- Be aware that Type 1 diabetics might have significant atherosclerotic deposits at a younger age than non-diabetics and can therefore have asymptomatic, but significant, vascular disease. Diabetes is the major reason for kidney disease under the age of 25 years and the main cause for dialysis at any age.

- There is an association between diabetes and periodontal disease but the issue of causation in the oral/systemic link with diabetes is controversial and under investigation.

- Dry mouth and xerostomia are common signs and symptoms in diabetics.

- Hyperglycemia can lead to impaired granulocyte phagocytosis and chemotaxis. Data are unclear as to the risks for postoperative infection following dental procedures.

In Well-Controlled Diabetes

- Patients should be scheduled for morning appointments and receive their normal insulin dose if they are able to eat after the procedure; otherwise, reduce the insulin dose.

- Ensure that the patient has eaten a normal breakfast, supplemented with orange or other sugar-containing juice.

- Have glucose available during the treatment.

- Resume normal insulin and oral intake immediately after the procedure.

- Periodontal disease is a common complication of diabetes and it can contribute to poor glycemic control and mortality from ischemic heart disease and nephropathy.

- Annual dental examination is recommended in both dentate and non-dentate diabetic patients. In a 2004 U.S. survey, 67% of respondents with diabetes reported a dental visit in the preceding twelve months.

In Poorly Controlled Diabetes

Major concerns in dental management are avoiding hypoglycemia in the dental office and a poor response to dental and periodontal infections.

- Consider consulting the patient’s physician for extensive periodontal or oral surgical procedures.

- Avoid stressful procedures.

- Although antibiotic coverage is often recommended it is rarely if ever indicated for invasive dental procedures, and there are no data to support this practice. Although there is in vivo evidence to suggest an increased risk of infection (from decreased neutrophil function) this is not evident clinically. However, infection in diabetics is often difficult to control and their medical management can be complicated by even asymptomatic oral infection (e.g., generalized periodontitis).

- Issues of increased risk of oral infection and impaired wound healing are controversial.

- Problems with infection: Admission to the hospital might be indicated for any diabetic with severe oral infection.

- The insulin requirement may be affected by oral infection or generalized periodontal disease: Discussion with the physician about the need to adjust insulin dose may be warranted after resolution of the infection.

Drug Abuse

Prescription and Non-Prescription Drugs

Significance of the Problem

The Fourth Edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM IV) gives a list of 11 classes of substances that can cause intoxication, abuse, and dependence:

- Intoxication: Reversible syndrome of maladaptive behavioral or psychological changes, such as mood lability, cognitive impairment, or poor judgment after ingestion of a substance

- Abuse: Pattern of substance use that results in job, interpersonal, or repeated legal difficulties, and/or recurrent substance use in physically hazardous situations

- Dependence: Maladaptive pattern of substance use characterized by repeated ingestion despite physical or psychological problems caused by the substance, ingesting larger amounts of the substance over longer periods, unsuccessful efforts to limit its use, tolerance to its effects, and physiologic withdrawal

Opioids

The prevalence of prescription opioid abuse in the United States has increased in the past decade, and has become one of the fastest growing drug problems in the nation.

Dental Considerations

- History taking for a patient who admits to abusing opioids should focus on the amount of drug used recently, route of administration, last use, previous attempts at drug treatment, and problems that have resulted from drug use. Using a direct approach and asking questions concerning drug abuse as part of the overall history taking makes this easier for both the patient and clinician.

- Keep meticulous records. Prescription numbers should be written out to avoid forgeries (e.g., “Disp: 10 (ten) tabs”).

- Opioids cause central nervous system depression and repeated use causes opioid tolerance.

- The risks of interaction between prescribed and abused drugs should be discussed with the patient.

- There is an increased incidence of hepatitis B and C and HIV in intravenous drug users. Liver function and coagulation tests should be checked for the possibility of decreased drug metabolism, coagulopathy, and possible chronic hepatitis.

- Between 1% and 7% of Caucasians of European descent have a genetic defect placing them at risk of respiratory depression from small doses of codeine. A patient history of adverse reactions to codeine consistent with intoxication should prompt selection of a different drug or markedly lower dose.

- Rampant caries can occur as a result of xerostomia, excess refined carbohydrates in diet, poor oral hygiene, and overall neglect.

- Concurrent psychiatric conditions are common.

- Defer elective care for patients that are under the influence of cocaine. Cocaine can potentiate cardiac arrhythmias in the presence of certain drugs (e.g., epinephrine).

Methamphetamines

Methamphetamines have a variety of stimulant, anorexiant, euphoric, and hallucinogenic effects. Recreational use has reached epidemic proportions in the United States and elsewhere in the world.

Dental Considerations

- Consider the possibility of methamphetamine intoxication and immediate medical referral for any diaphoretic patient with hypertension, tachycardia, severe agitation, and psychosis. Acutely intoxicated patients may become extremely agitated and pose a danger to themselves and others.

- Methamphetamine intoxication ranges from the virtually asymptomatic to those in sympathomimetic crisis with seizures, metabolic acidosis, and imminent cardiovascular collapse. They may be agitated with tachycardia and psychosis.

- Patient examination may identify mucosal injuries from insufflation (snorting), oropharyngeal burns in methamphetamine smokers, and gingival hypertrophy. Extensive caries (“meth-mouth”) and general destruction of the dentition is common in chronic methamphetamine abuse due to bruxism, decreased saliva production, and poor nutrition and dental hygiene.

Alcohol

Alcoholism is defined by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and the American Society of Addiction Medicine as “a primary chronic disease with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations.”

Significance of the Problem

- Approximately ten percent of Americans abuse alcohol.

- It is a highly prevalent and disabling condition, associated with high rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidity and early mortality.

- It is often progressive and fatal. It is characterized by impaired control over drinking, preoccupation with the drug alcohol, use of alcohol despite adverse consequences, and distortion of thinking, most notably denial.

- Alcohol can be a significant contributing factor to hepatitis, hypertension, tuberculosis, pneumonia, pancreatitis, and cardiomyopathy. Half of all cases of cirrhosis in the U.S. are due to alcohol abuse.

- Alcohol abuse contributes to cancers of the mouth, esophagus, pharynx, and larynx, especially in combination with tobacco use.

- It is associated with several psychiatric disorders, notably mood disorders such as depression, eating disorders, and anxiety disorders.

Dental Considerations

- Treatment should be deferred with patients that appear to be under the influence of alcohol because of the risk of injury, decreased gag reflex, and problems of informed consent. Morning appointments may be best.

- Alcoholic liver disease may be associated with laboratory abnormalities including but not limited to:

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST or SGOT)

- Alanine aminotransferases (ALT or SGPT)

- Gammaglutamyl transferase (GGT)

- The most common pattern of liver biochemical test abnormalities with alcoholic hepatitis is a disproportionate elevation of serum AST compared with ALT, usually greater than a 2:1 ratio.

- Consider laboratory tests to assess bleeding tendencies (PT/INR to detect vitamin-K-dependent Factors II, VII, IX, X) and liver function (e.g., ability to metabolize medications): Hepatitis screen, AST, ALT, bilirubin, albumin; HIV (if indicated) (Appendix 18).

- A history of delirium tremens (occurs 72 hours to 96 hours after the last drink) is important because this can be fatal without appropriate medical management.

- Opioids should be avoided due to concern for respiratory depression when combined with alcohol.

- Educational materials on this topic are available for patients.

- www.uptodate.com/patients

- World Health Organization (www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/en)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (www.niaaa.nih.gov)

- A possible relationship between alcohol-containing mouth rinses and oral cancer has been suggested. This relationship has not been firmly established, but for the time being the use of alcohol-containing mouth rinses in high-risk populations should be restricted

Fever of Unknown Origin

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is defined as a prolonged febrile illness without an established etiology despite intensive evaluation and diagnostic testing. Evaluation for an oral source comes late in the evaluation for a source of FUO because true FUO would be a very rare finding in a non-immunosuppressed patient without any oral signs or symptoms or oral infection.

Classification