Traumatic Dental Injuries: Examination, Diagnosis, and Immediate Care

Eva Fejerskov Lauridsen, Simon Storgård Jensen, and Jens O. Andreasen

It is well documented that the majority of traumatic dental injuries occur in children. Thus, in a Swedish study, 83% of all individuals with acute dental trauma were younger than 20 years of age [1]. Injuries to primary or permanent teeth can appear rather severe, particularly when associated with trauma to supporting tissues (Figures 18.1 and 18.2). The situation is distressing for both the child and parents. It is important that the dentist and the other members of the dental team are well prepared to meet the many complex and challenging problems in the care of dental emergencies (Box 18.1).

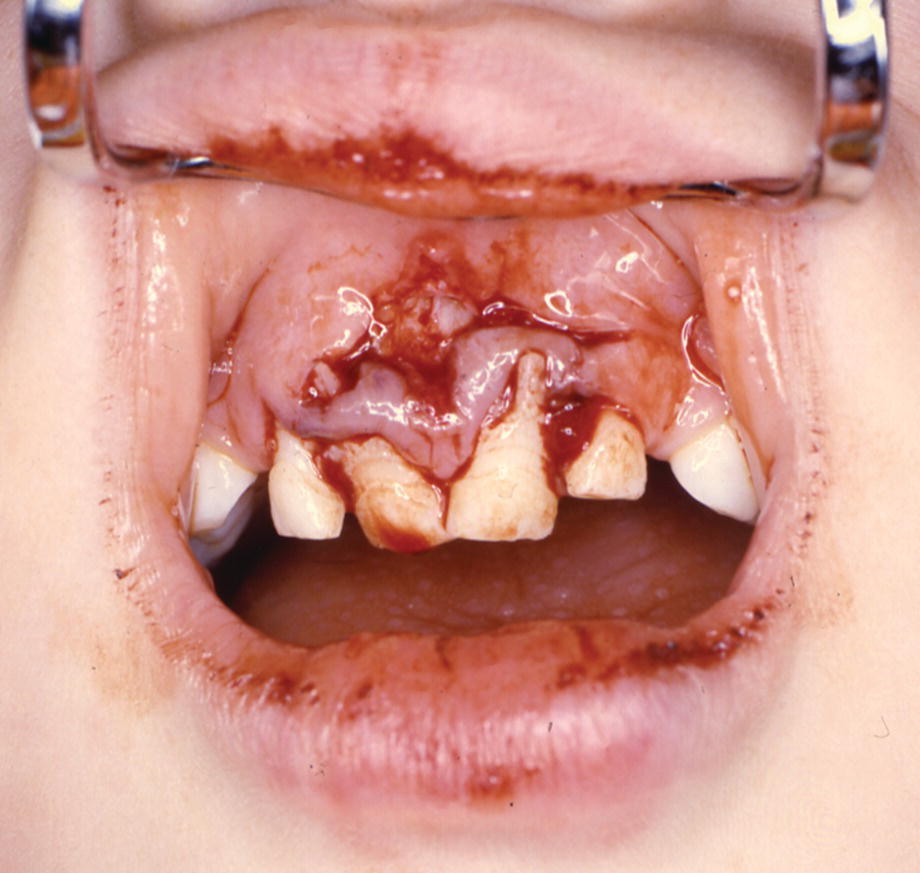

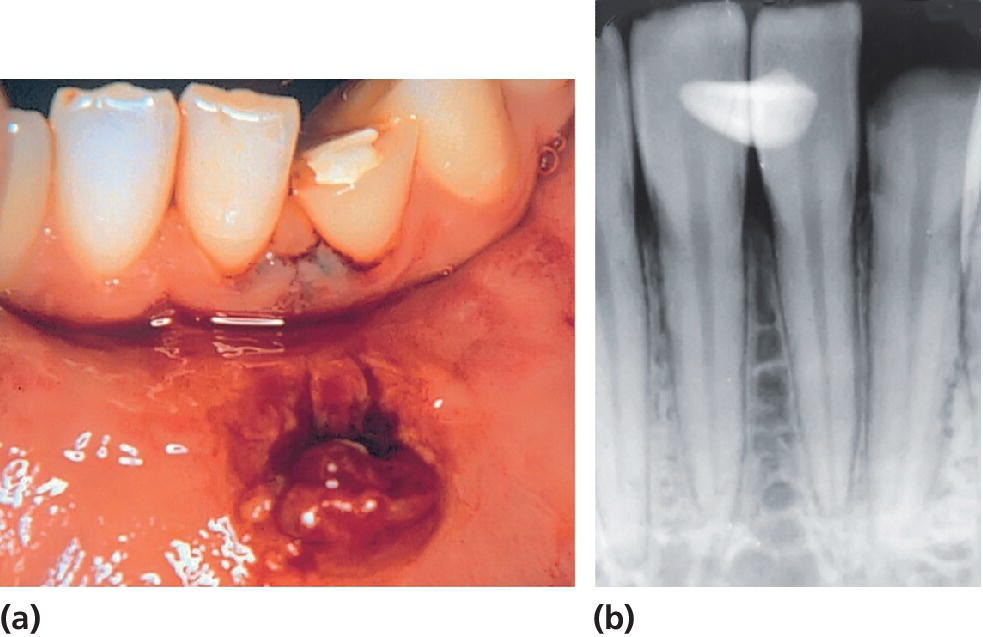

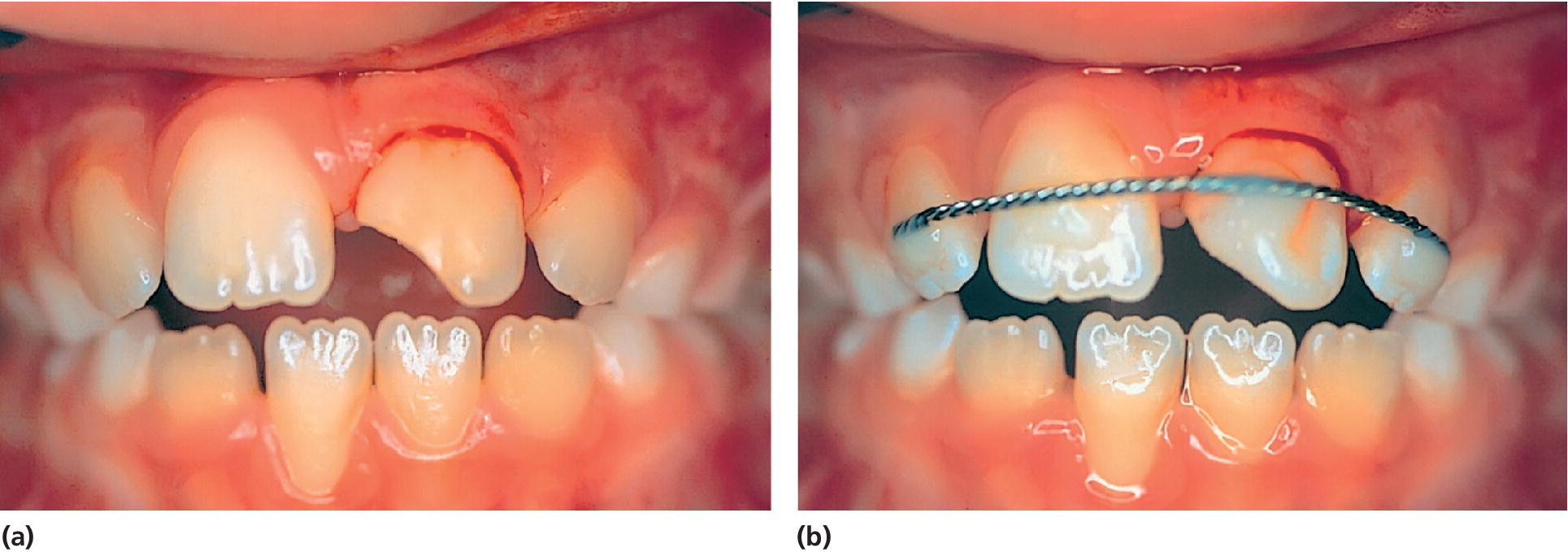

Figure 18.1 A 4‐year‐old boy with lateral luxation of three primary incisors and extensive gingival laceration.

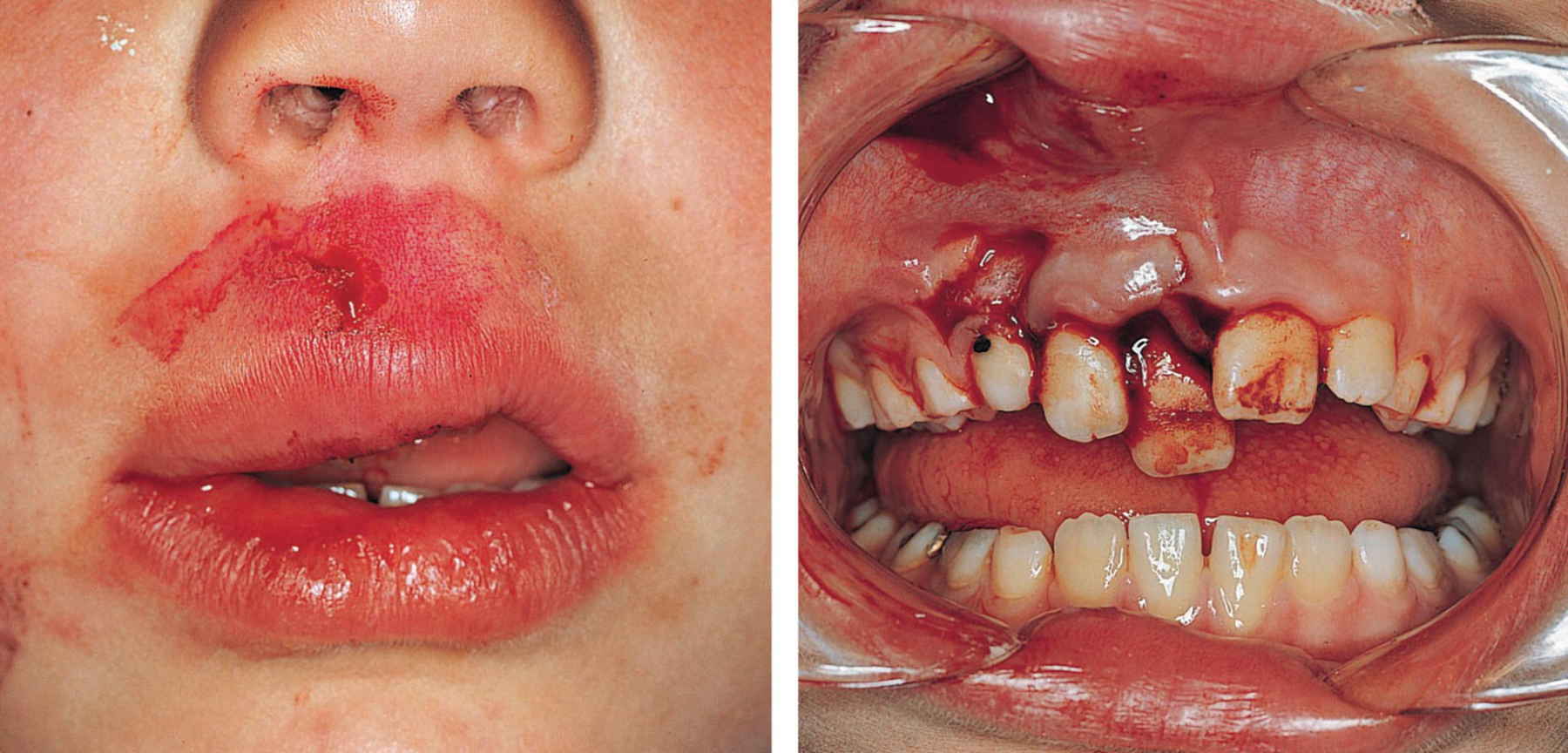

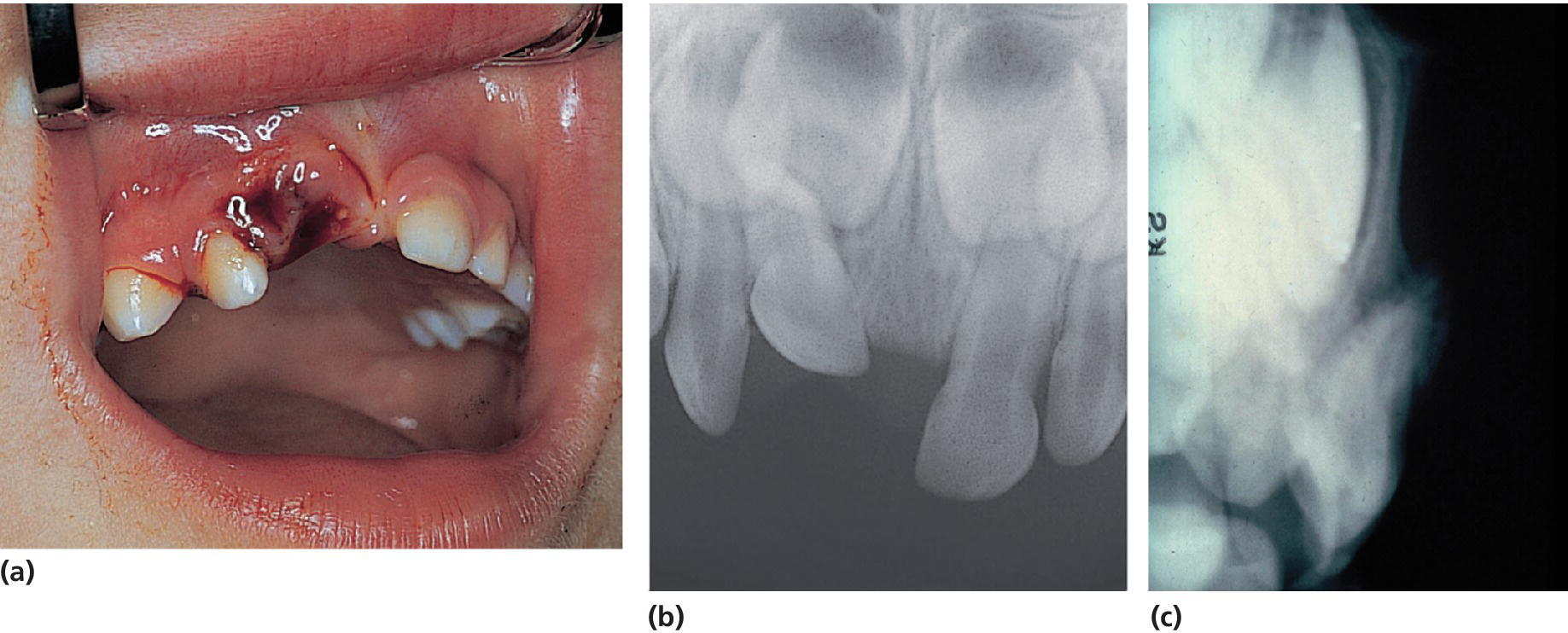

Figure 18.2 The patient has had an impact where the force has been transmitted through the upper lip to the teeth and the alveolar process. Note the lip laceration and abrasion and the displacement of the right central and lateral incisors.

Epidemiology

Traumatic dental injuries are frequent. A Danish study showed that 30% of children had suffered traumatic dental injuries in the primary dentition and 22% in the permanent dentition [2]. The incidence of injuries to primary teeth increases from 1 year of age, and most traumas involve children younger than 4 years of age. In the permanent dentition, the most accident‐prone time is between 8 and 10 years of age (Figure 18.3). Boys appear to sustain injuries to permanent teeth twice as often as girls. Traumatic dental injuries usually affect one or two of the anterior teeth, and especially the maxillary central incisors (Figure 18.4) [3].

Figure 18.3 Percentage distribution of 1275 children with traumatic dental injuries related to age at the time of injury.

Source: Skaare & Jacobsen 2003 [3]. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 18.4 Distribution of injuries of the most frequently injured permanent teeth: 97% of all injuries affected the incisors.

Source: Skaare & Jacobsen 2003 [3]. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Etiology

In a young child learning to walk and to run, muscle coordination and judgment are incompletely developed and falling injuries frequently occur. Trauma to the orofacial area may also be part of child physical abuse. The characteristics of this unfortunate condition are presented in Box 18.2.

A Norwegian study of children aged from 7 to 18 years reported that 48% of all dental traumas occurred during school hours and 52% during leisure time. Nearly half of the leisure‐time injuries occurred when children were playing. Ten percent happened in traffic, and half of these were bicycle accidents. Twenty‐five percent occurred while partying or visiting bars and clubs [4].

In contrast to common belief, only 8% of all injuries were sports related. Finally, in the age group 16–18 years, 23% of all orofacial injuries resulted from violence [4].

Examination

To ensure that all relevant data are recorded, a standardized trauma form is recommended [5]. This form serves as a checklist for the dentist at the initial visit and at subsequent appointments.

History

When the patient is received for treatment, the first step is to gain an initial impression of the extent of the injury. Is there a need for immediate medical care? Is the patient’s general condition affected? If not, the following questions should be asked to end up with a correct diagnosis, and allow treatment planning:

- When did the injury occur? The time interval between injury and treatment can influence both the treatment procedure and the expected outcome. Thus, optimal repositioning of a displaced permanent tooth is difficult if treatment is delayed. The time factor is also very critical for the prognosis of avulsed teeth.

- Where did the injury occur? This information is important for insurance and social security purposes. The place of accident also provides information on the need for tetanus prophylaxis in replantation cases.

- How did the injury occur? The nature of the blow may provide clues as to the type of injury to be expected. For example, when a blow hits the chin, the mandibular arch is forced against the maxillary arch, with jaw fracture or crown–root fractures in the premolar or molar regions as possible resulting injuries.

- Was there a period of unconsciousness? If so, for how long? Is there headache? Amnesia? Nausea? Vomiting? Excitation or difficulties in focusing the eyes? These are all signs of brain concussion and require medical attention.

- Is there any disturbance in the occlusion? Can imply luxation injury, alveolar fracture, jaw fracture, or luxation or fracture of the temporomandibular joint. Limitations of mandibular movement or mandibular deviation on opening or closing the mouth indicate that the jaw may be fractured.

- Have there been previous injuries to the teeth? Answers to this may explain radiographic findings, such as pulp canal obliteration and incomplete root formation in a dentition with otherwise completed root development.

Medical history

A short medical history should include information about medication, allergies, bleeding disorders, and other conditions that could interfere with treatment or prognosis. Ask also if the patient is covered by antitetanus vaccination.

Extraoral examination

Palpation of the facial skeleton and mandible and note is taken of soft tissue swelling, bruises, or lacerations to the face and lips. Deep lip wounds are examined closely with respect to tooth fragments or other foreign bodies (Figure 18.5).

Figure 18.5 (a) Crown fracture of mandibular lateral incisor and mandibular lip lesion. (b) A radiograph reveals the fractured tooth fragment hidden in the lip lesion.

Intraoral examination

The examination must be systematic and include the recording of:

- swelling, laceration, and hemorrhage of the oral mucosa and gingiva

- abnormalities in occlusion

- missing, displaced or mobile teeth, fractured crowns, or cracks in the enamel.

It is important to examine all teeth within a traumatized area and, in close bite situations, also teeth in the opposite jaw. Particular note is taken of the following factors:

- Displacement. The direction (intrusion, extrusion, retrusion or protrusion) as well as the extent (in millimeters) of displacement should be recorded. Minor displacements can be difficult to detect. In such cases it is helpful to examine the occlusion as well as radiographs taken at various angulations.

- Mobility. The degree of mobility is assessed in both a horizontal and vertical direction, keeping in mind that immature permanent teeth and primary teeth undergoing root resorption may have quite extensive physiologic mobility. When several teeth move together en bloc, a fracture of the alveolar process should be suspected.

- Reaction to percussion. The handle of a mouth mirror is tapped gently against the teeth in both a horizontal and vertical direction. Tenderness to percussion indicates damage to the periodontal ligament. A high metallic tone implies that the injured tooth is locked in bone.

- Color of the tooth. Discoloration may appear almost immediately after the injury. Special attention should be paid to the palatal surface in the gingival third of the crown.

- Reaction to sensibility tests. It is usually not possible to obtain reliable information from a young, frightened child. However, in the permanent dentition electrometric sensibility testing should be performed whenever possible. It gives important information about the neurovascular supply to the pulp, and provides a baseline value for comparison at follow‐up examination. The contralateral uninjured tooth or another comparable tooth serves as a control. The most reliable response is obtained when the electrode is placed upon the incisal edge. It is important to explain the purpose of the test and the type of reaction to be expected.

Radiographic examination

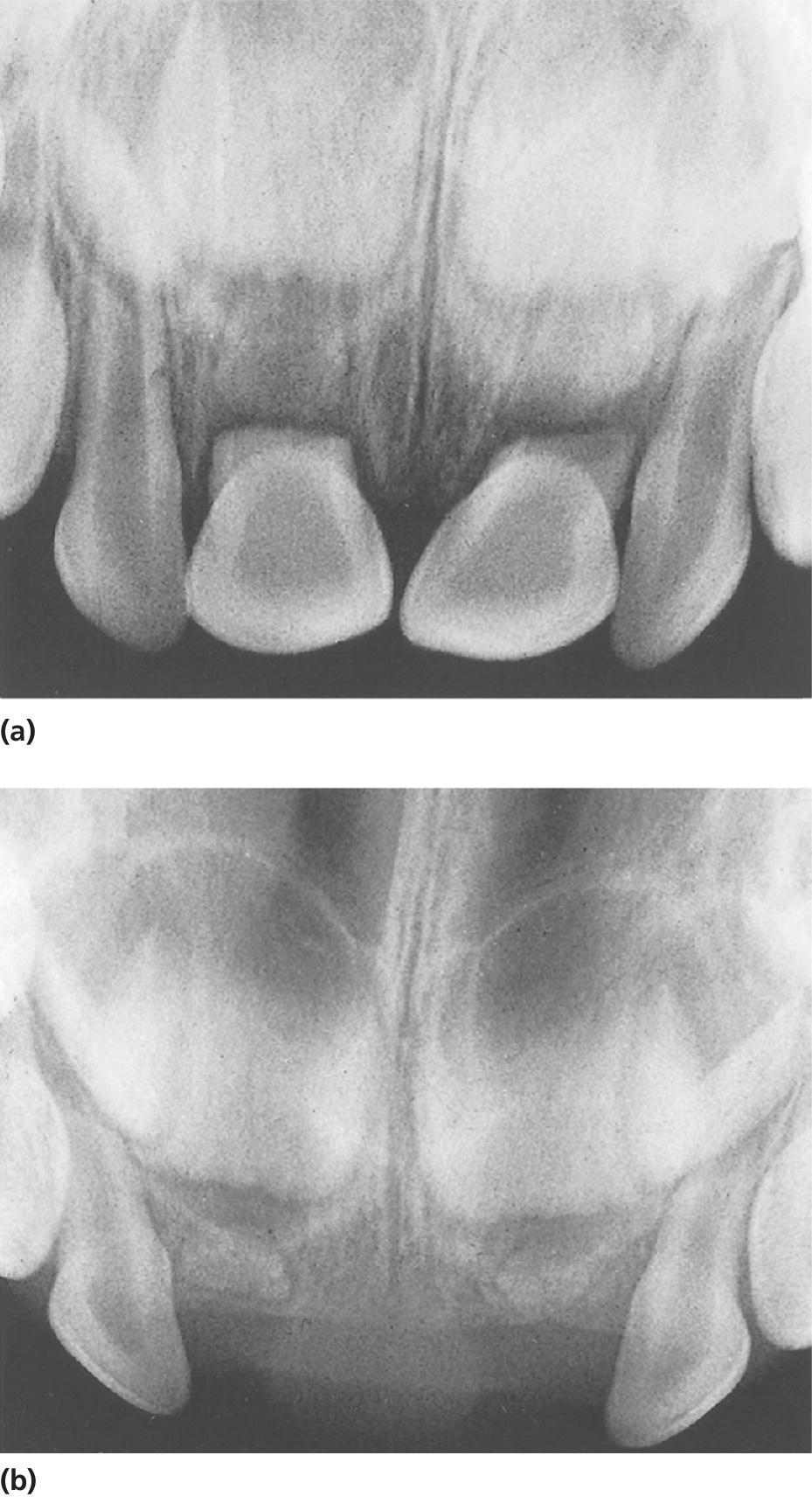

A detailed radiographic examination is mandatory in order to obtain an impression of the injury to the teeth, supporting tissues, the stage of root development and, in the case of primary tooth injuries, the relation to permanent successors (Figure 18.6). Before a radiographic examination is carried out, a clinical examination should establish the extent of the trauma region. This area is then radiographed; ideally, the injury site should be viewed from different angulations [6].

Figure 18.6 (a) Clinical condition immediately after severe intrusive luxation of the primary right central incisor. (b) The occlusal exposure shows foreshortening of the intruded tooth, indicating buccal displacement away from the permanent follicle. (c) This is evident in the lateral radiograph, since the apex of the intruded incisor is forced through the buccal bone plate.

Permanent teeth

For an injured anterior front with all incisors involved, four exposures should be taken (one occlusal and three bisecting angle exposures), where the central beam is directed interdentally between the incisors. This combination of radiographs results in each traumatized tooth being seen from different angulations, which increases the likelihood of diagnosing even minor dislocations (Figure 18.7).

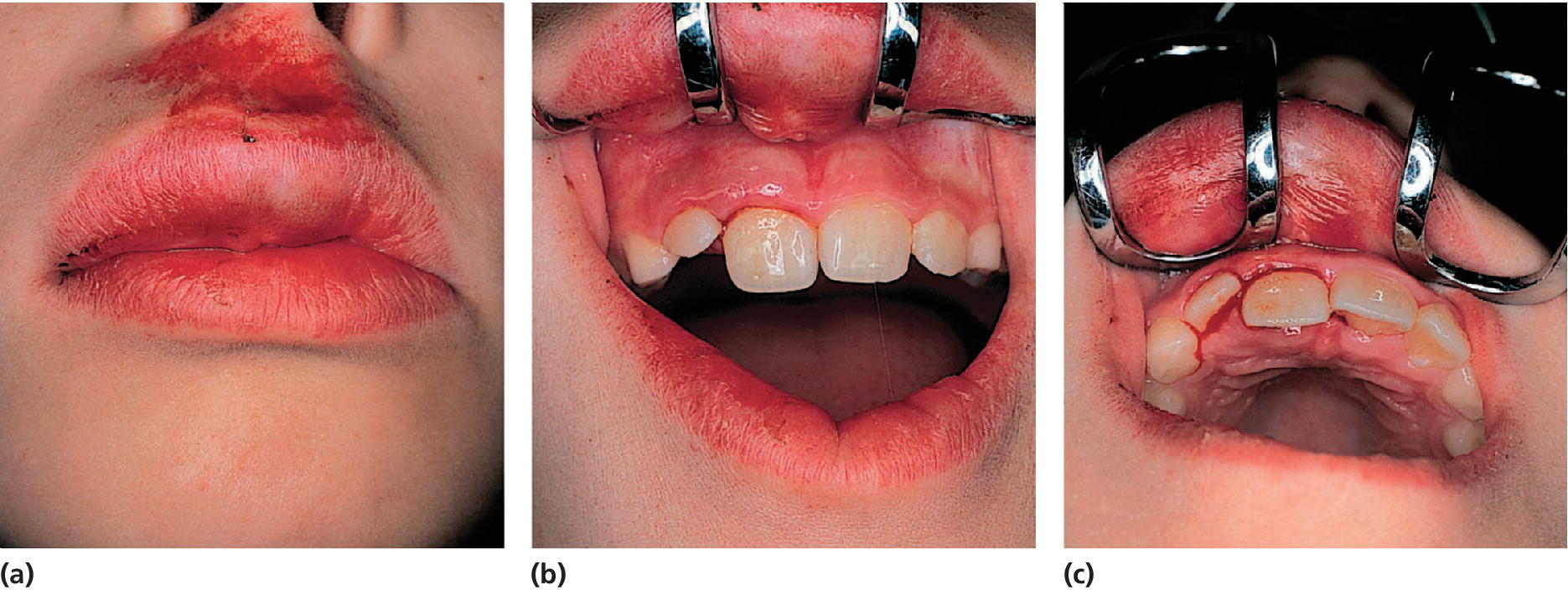

Figure 18.7 (a–c) Clinical appearance after lateral luxation of the right central incisor. (d–g) One occlusal and three periapical radiographs. Note that the occlusal exposure is optimal for showing the buccal displacement of the root. (h) The lateral radiograph illustrates where the fracture of the buccal bone plate has occurred (arrow).

In deep lip wounds a soft tissue radiograph is essential to diagnose embedded tooth fragments or other foreign bodies. A film is placed between the lips and the alveolar process, and the exposure time should be approximately 25% of a dental exposure time.

Primary teeth

A young child is often difficult to examine radiographically because of fear or lack of cooperation. However, with the parents’ help, it is usually possible to obtain a radiograph of the traumatized area (see also Chapter 8). In these instances an occlusal film held by the parents and a steep exposure angle should be used. This will normally show the position of the displaced tooth and its relation to the permanent successor. However, an extraoral lateral exposure may give additional information in case of suspicion of collision between the primary tooth and the permanent tooth germ.

Diagnosis

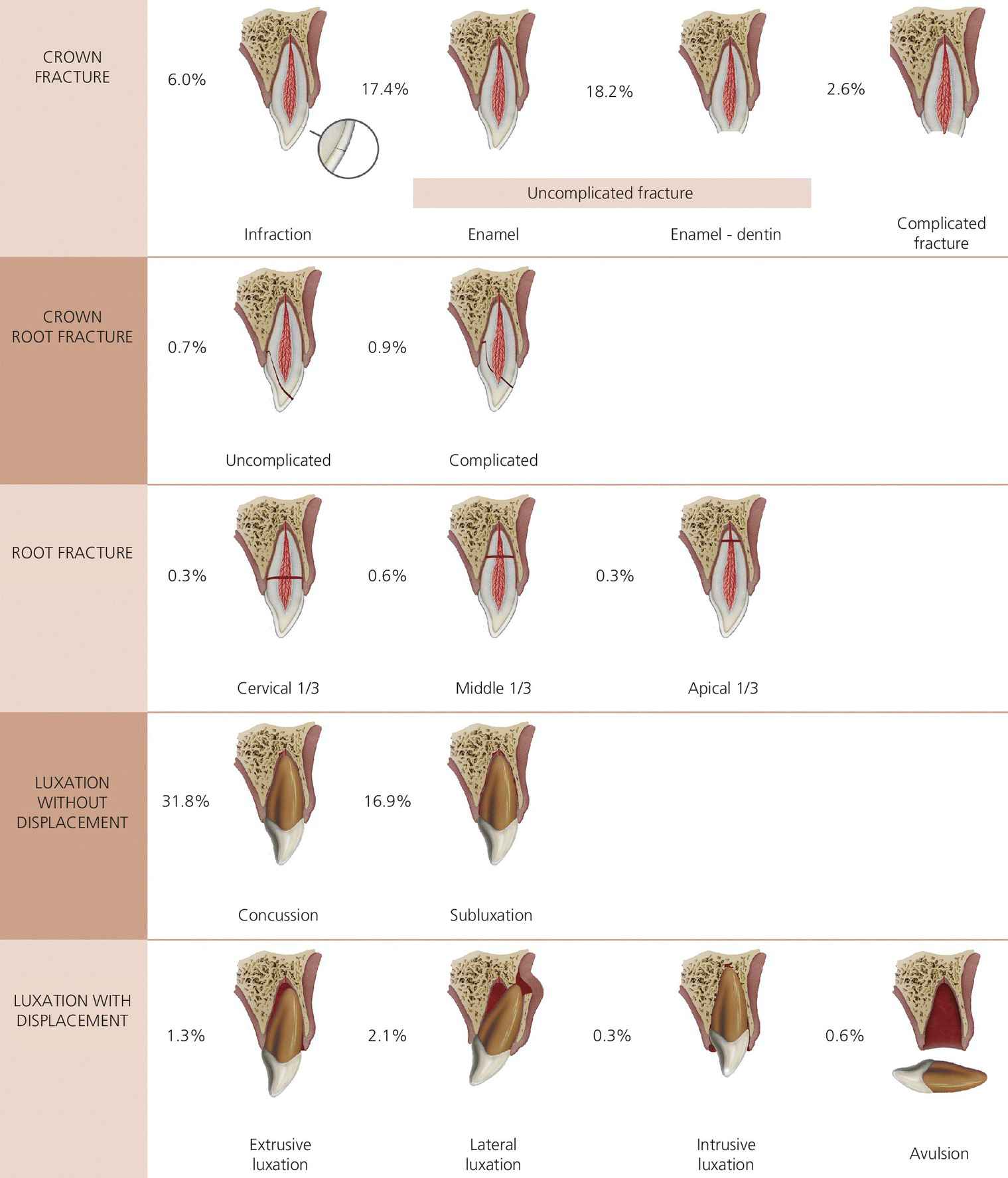

With combined information from the clinical and radiographic examination, a diagnosis is made and the injury is classified as a guide to the treatment required. In this chapter the classification recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) will be used. The code numbers are according to the International Classification of Diseases [7].

Injuries to the hard dental tissues and the pulp

- Enamel infraction (S 02.50). An incomplete fracture (crack) of the enamel without loss of tooth substance.

- Enamel fracture (uncomplicated crown fracture) (S 02.50). A fracture with loss of tooth substance confined to the enamel.

- Enamel–dentin fracture (uncomplicated crown fracture) (S 02.51). A fracture with loss of tooth substance confined to enamel and dentin, but not involving the pulp.

- Complicated crown fracture (S 02.52). A fracture involving enamel and dentin, and exposing the pulp.

Injuries to the hard dental tissues, the pulp, and the alveolar process

- Crown–root fracture (S 02.54). A fracture involving enamel, dentin, and cementum. It may or may not expose the pulp (uncomplicated and complicated crown–root fracture).

- Root fracture (S 02.53). A fracture involving dentin, cementum, and the pulp. Root fractures can be further classified according to displacement of the coronal fragment and localization of the fracture.

- Fracture of the mandibular (S 02.60) or maxillary (S 02.40) alveolar socket wall. A fracture of the alveolar process that involves the alveolar socket.

- Fracture of the mandibular (S 02.60) or maxillary (S 02.40) alveolar process. A fracture of the alveolar process that may or may not involve the alveolar socket.

Injuries to the periodontal tissues

- Concussion (S 03.28). An injury to the tooth‐supporting structures without abnormal loosening or displacement of the tooth, but with marked reaction to percussion.

- Subluxation (S 03.28). An injury to the tooth‐supporting structures with abnormal loosening, but without displacement of the tooth.

- Extrusive luxation (S 03.21). Partial displacement of the tooth out of its socket.

- Lateral luxation (S 03.20). Displacement of the tooth in a direction other than axially. This is accompanied by comminution or fracture of the alveolar socket.

- Intrusive luxation (S 03.21). Displacement of the tooth into the alveolar bone. This is accompanied by comminution or fracture of the alveolar socket.

- Avulsion (exarticulation) (S 03.22). Complete displacement of the tooth out of its socket.

Injuries to gingiva or oral mucosa

- Laceration of gingiva or oral mucosa (S 01.50). A shallow or deep wound in the mucosa resulting from a tear; usually produced by a sharp object.

- Contusion of gingiva or oral mucosa (S 01.50). A bruise usually produced by impact with a blunt object and not accompanied by a break in the mucosa, usually causing submucosal hemorrhage.

- Abrasion of gingiva or oral mucosa (S 01.50). A superficial wound produced by rubbing or scraping of the mucosa, leaving a raw, bleeding surface.

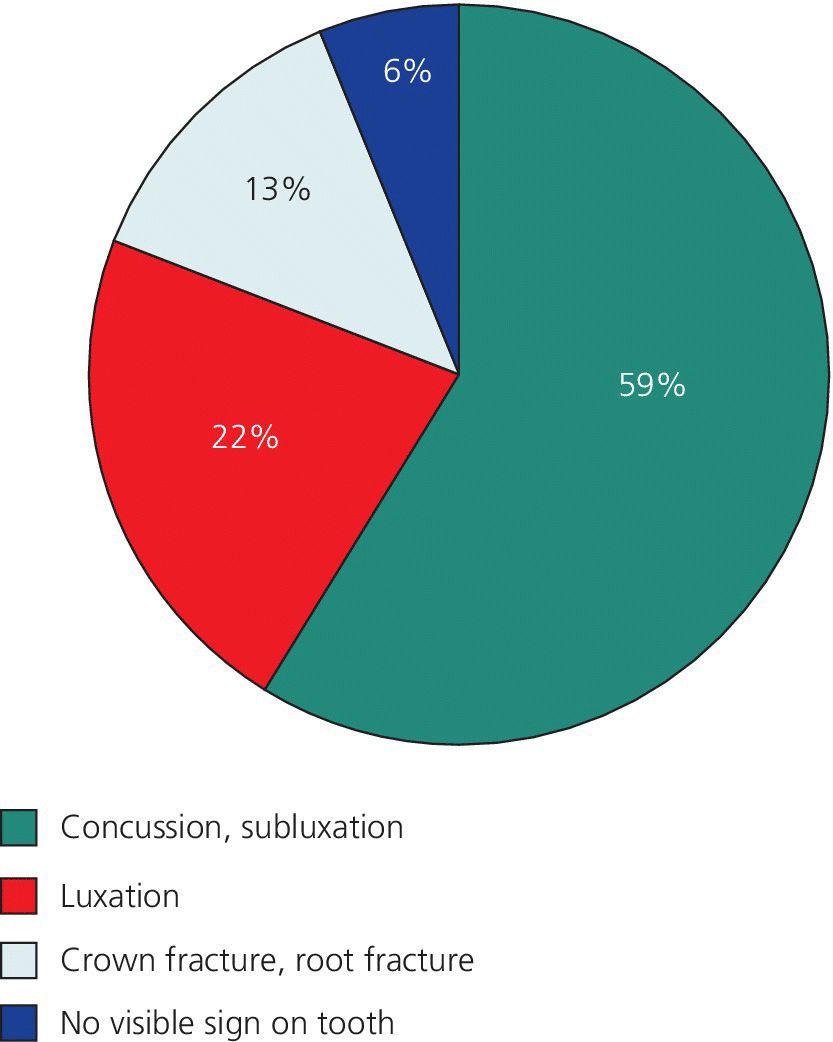

The distribution of various dental diagnoses in the primary and permanent dentition is shown in Figures 18.8 and 18.9, respectively. In the permanent dentition uncomplicated crown fractures are very common [3]. In contrast, luxation injuries dominate in the primary dentition [8]. This is probably due to resilience of the alveolar bone in young children, favoring loosening or displacement rather than fractures of the hard dental tissues.

Figure 18.8 Percentage distribution of diagnoses for traumatized primary teeth.

Source: Heintz 1968 [25]. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

Figure 18.9 Distribution of 2019 traumatized permanent teeth according to diagnosis in 1275 children aged 7–18 years.

Source: Skaare & Jacobsen 2003 [3]. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Immediate care: primary teeth

During its early development, the permanent incisor is located palatally and in close proximity to the apex of the primary incisor (Figure 18.10). Consequently, with injuries to primary teeth, the dentist must always be aware of possible damage to the underlying permanent teeth.

Figure 18.10 Schematic drawing illustrating developmental disturbance of permanent tooth bud at the age of 2 years. The crown of the primary incisor is displaced buccally, forcing the root into the crown of the developing permanent incisor.

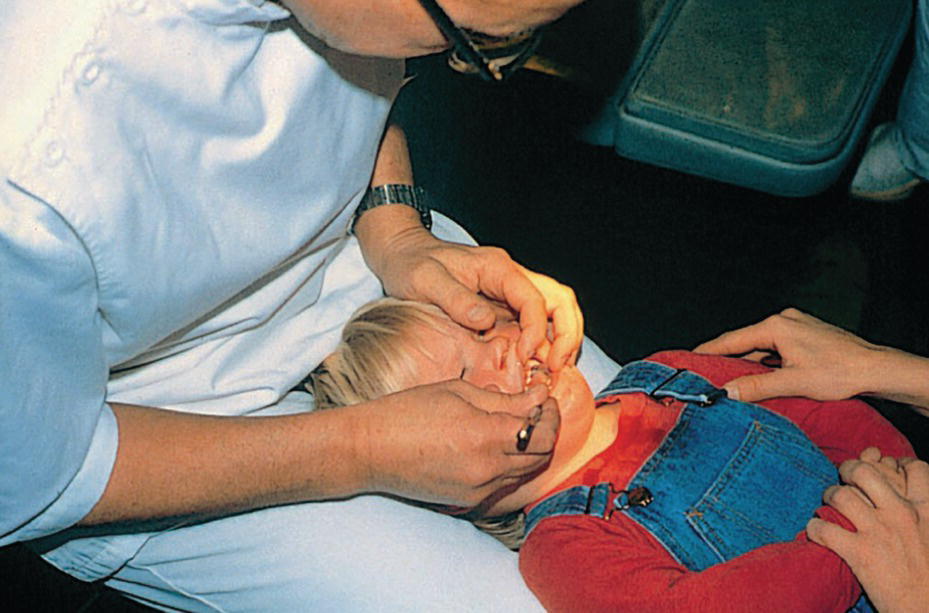

A young child is often unable to cooperate, and the following procedure is suggested for clinical examination (Figure 18.11):

- The parent is seated on a chair with the child on his or her lap, facing the parent.

- The dentist, who is seated behind the child, receives and steadies the child’s head in the lap.

- The parent gently restrains the child’s arms and legs.

Figure 18.11 Procedure for examination of a young child’s mouth (see text).

In this way, a thorough examination of the oral structures can easily be done in a few minutes.

With the assistance of a parent or another adult, it is also possible to obtain radiographs of the traumatized area. However, active treatment such as splinting of loosened teeth or endodontic therapy may be extremely difficult. Therefore, in the majority of cases, the dentist has to decide whether the traumatized tooth is best treated by extraction, or whether it can be maintained without any extensive treatment.

A primary incisor should always be removed if its maintenance will jeopardize the developing permanent tooth bud, i.e., if the displaced primary tooth has invaded the follicle of the permanent successor [9]. If treatment is required in a young child, the use of conscious sedation should be considered (Chapter 9).

Enamel and enamel–dentin fracture

Most crown fractures consist of enamel or superficial enamel–dentin fractures. In both situations, slight grinding of sharp edges is sufficient. If the fracture is extensive, and the child cooperative, the tooth can be restored with glass‐ionomer cement or composite [9].

Complicated crown fracture

Normally, extraction is the treatment of choice. However, if full cooperation of the child can be achieved, the same procedure as outlined for permanent teeth can be followed [9].

Crown–root fracture

These cases involve fracture of enamel, dentin, and cementum. Frequently, the pulp is also exposed. Restorative treatment is extremely difficult and the tooth is best extracted [9].

Root fracture

If the coronal fragment is severely dislocated, extraction is the treatment of choice. No effort should be made to remove the apical fragment, as such intervention might damage the underlying permanent tooth. After removal of the coronal fragment, uncomplicated resorption of the apical fragment should be expected (Figure 18.12). Without evident displacement, the coronal fragment may show little mobility, and no immediate extraction is required. The tooth should be kept under observation. Sometimes necrosis develops in the coronal fragment, whereas the apical portion nearly always remains vital. In these cases the coronal fragment only should be extracted [9].

Figure 18.12 (a) Fractured roots of both central incisors with dislocation of the coronal fragments. (b) Normal resorption of the apical fragments after removal of the coronal fragments.

Luxation injuries

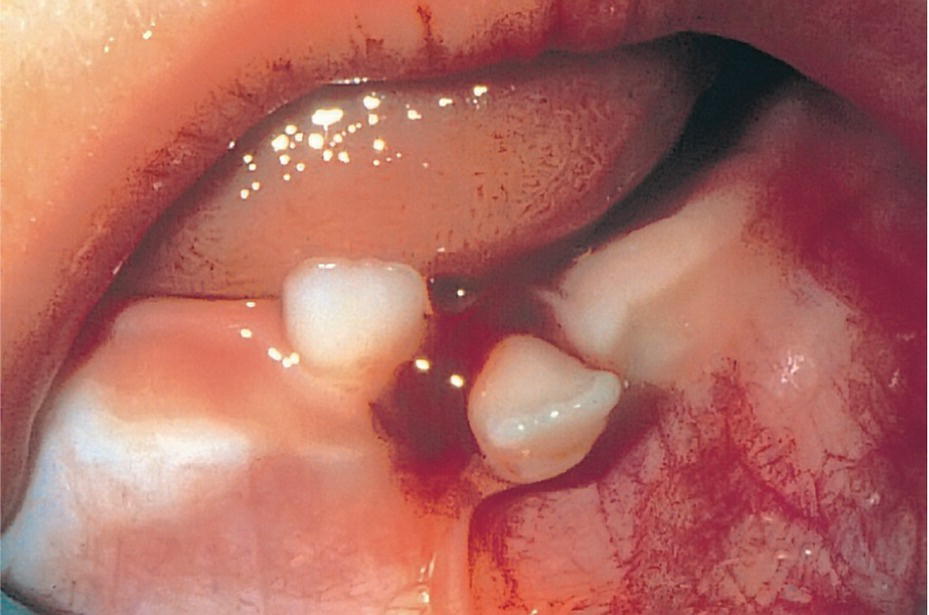

These injuries dominate in the primary dentition. Most often, the patients also have extensive soft tissue damage such as swollen lips, lacerations, and hemorrhage of the oral mucosa and gingiva (Figure 18.13). The parents are instructed to clean the traumatized area gently with 0.1% chlorhexidine solution, using cotton swabs (twice daily for a week). Normally the soft tissue heals quickly. Swelling will usually subside within a week.

Figure 18.13 Severe soft tissue damage with extensive hemorrhage. Both central incisors and the right lateral incisor are extruded and extremely mobile.

Concussion

Most concussions are not seen by the dentist at the time of the accident. The parents may see no need to seek dental treatment, or they may not be aware of the injury until tooth discoloration appears.

Subluxation

The parents are advised to keep the traumatized area as clean as possible, and to feed the child on a soft diet for a few days [9]. Mobility should diminish within 1–2 weeks.

Extrusive luxation

An extruded tooth may be repositioned by digital pressure. However, if the tooth is severely displaced and shows considerable mobility, the tooth is best treated by immediate extraction [9].

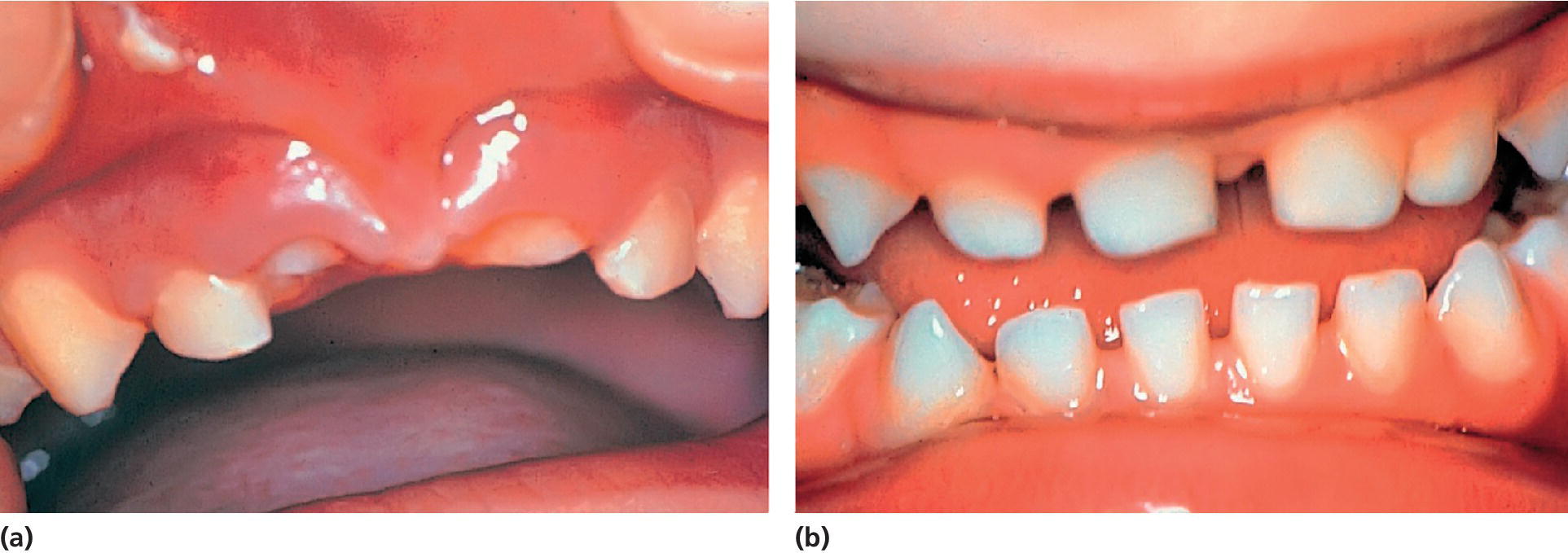

Lateral luxation

- Palatal displacement of the crown is most common. This implies that the apex is forced in a buccal direction and thus away from the permanent tooth germ. If there is no interference with the occlusion these teeth can be left untreated. Over a period of 1–2 months, tongue pressure will usually reposition the tooth (Figure 18.14).

- In the case of minor occlusal interference, slight grinding is indicated. When there is more severe occlusal interference, the tooth can be gently repositioned by combined labial and palatal pressure after the use of local anesthesia or the tooth may be extracted [9].

- Buccal displacement of the crown (Figures 18.10 and 18.15). The root will be displaced palatally in the direction of the permanent tooth bud. In case of collision with the permanent tooth germ, extraction is the treatment of choice [9].

Figure 18.14 (a) Severe palatal luxation of the right central incisor. No treatment other than observation was performed. (b) Two months later, the tooth is back in normal position due to tongue pressure.

Figure 18.15 Clinical condition immediately after buccal displacement of the left central incisor in an 8‐month‐old girl.

Intrusive luxation

An intruded tooth often shows severe displacement. Sometimes it will be completely intruded into the alveolar process and mistakenly assumed to be lost, until a radiograph shows the intruded position (Figure 18.16). With all intrusions, it is essential to clarify whether the root is forced in a palatal or buccal direction. The diagnosis should be based on a combined clinical and radiographic examination.

Figure 18.16 (a) Clinical examination after trauma of an 18‐month‐old child. The parents assumed that the right central incisor was lost. (b) The radiograph reveals severe intrusive luxation. Additional radiographs should be taken to disclose the exact direction of the intrusion (see Figure 18.6).

Clinical examination

Due to a buccal curve of the apex, the primary root tends to be displaced through the buccal bone plate. It is advisable to palpate the buccal sulcus. If part of the crown is visible, the tooth crown axes will also indicate the direction.

Radiographic examination

A foreshortened appearance of the intruded tooth implies buccal displacement of the root and thus away from the permanent tooth germ, whereas an elongated image suggests palatal displacement towards the permanent successor (Figure 18.6).

Treatment

In most cases the root will be displaced in a buccal direction and the primary tooth can be left to re‐erupt spontaneously [9]. The parents are instructed to clean the traumatized area with 0.1% chlorhexidine solution for a week. During the re‐eruption phase, there is a risk of infection, and the patient should therefore be seen for follow‐up a week after the injury. Signs of infection include swelling, spontaneous bleeding, and abscess formation. There may also be a rise in body temperature. In these cases, the traumatized tooth must be removed and antibiotic therapy instituted. Without signs of infection, re‐eruption will generally take place within 2–6 months (Figure 18.17). If re‐eruption fails to occur, ankylosis should be suspected. If the ankylosed tooth interferes with eruption of the permanent successor, it must be removed [9].

Figure 18.17 (a) Condition immediately after intrusive luxation of both central incisors. (b) Re‐eruption is evident 6 months later.

If the primary root is displaced palatally, into the follicle of the developing tooth germ, extraction is recommended [9]. Extraction is performed to minimize the risk of bacterial invasion into the follicle which could cause further damage to the developing permanent tooth. Elevators should never be used to luxate the intruded incisors. Forceps should be the only instrument employed for this purpose. The intruded tooth should be grasped mesiodistally and lifted out of its socket in an axial direction. Thereafter digital pressure should be applied to the buccal and palatal aspects of the socket to reposition the displaced bone plates.

Avulsion

A radiographic examination is essential to ensure that the missing tooth is not intruded (Figure 18.16). Replantation is contraindicated, as pulp necrosis is a frequent complication. Moreover, there is a risk of further injury to the permanent tooth germ by the replantation procedure, whereby the coagulum from the socket can be forced into the follicle [9].

Immediate care: permanent teeth

The most common age of trauma to the permanent dentition is between 8 and 10 years (Figure 18.3). This implies that a traumatized tooth often has an open apical foramen, a wide root canal, and fragile dentinal walls in the cervical area. If pulp necrosis develops, no further dentin apposition occurs, and there is a considerable risk of spontaneous root fracture cervically with subsequent loss of the injured tooth (see Chapter 19). Consequently, the primary concern is to maintain pulp vitality to allow continued root formation including physiologic dentin apposition in the critical cervical area. The following recommendations for treatment of acute traumatic injuries is based on the treatment guidelines developed by the International Association of Dental Traumatology [10,11].

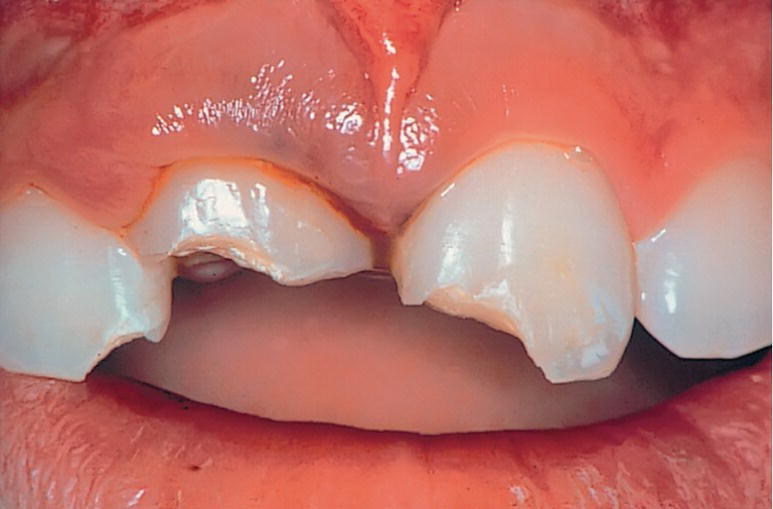

Crown fractures

It is most important to diagnose concomitant periodontal injuries, since the risk of complications to crown fractures is significantly increased with an additional luxation injury (Figures 18.18 and 18.19) [12–14].

- Enamel infraction. Infractions are incomplete fractures without loss of tooth substance. The fracture line usually stops at the enamel–dentin junction. Infraction lines are best seen when the light beam is directed parallel to the long axis of the tooth. In case of concomitant luxation injury sealing of the infraction line with resin is recommended.

- Enamel fracture. Minimal tooth substance is lost, and restoration is normally not needed. Often, a slight contouring of the fractured angle will provide an esthetically satisfactory result.

- Enamel–dentin fracture. Some typical examples are shown in Figures 18.18 and 18.19. Crown fractures involving dentin result in exposure of dentinal tubules to the oral environment. If the dentin is left unprotected, bacteria or bacterial toxins may penetrate the tubules, resulting in pulpal inflammation. Although the inflammation may be reversible, pulp necrosis is also a possible outcome. The pulp should therefore be protected against external irritants as quickly as possible, and the tooth crown restored by one of the following restorations.

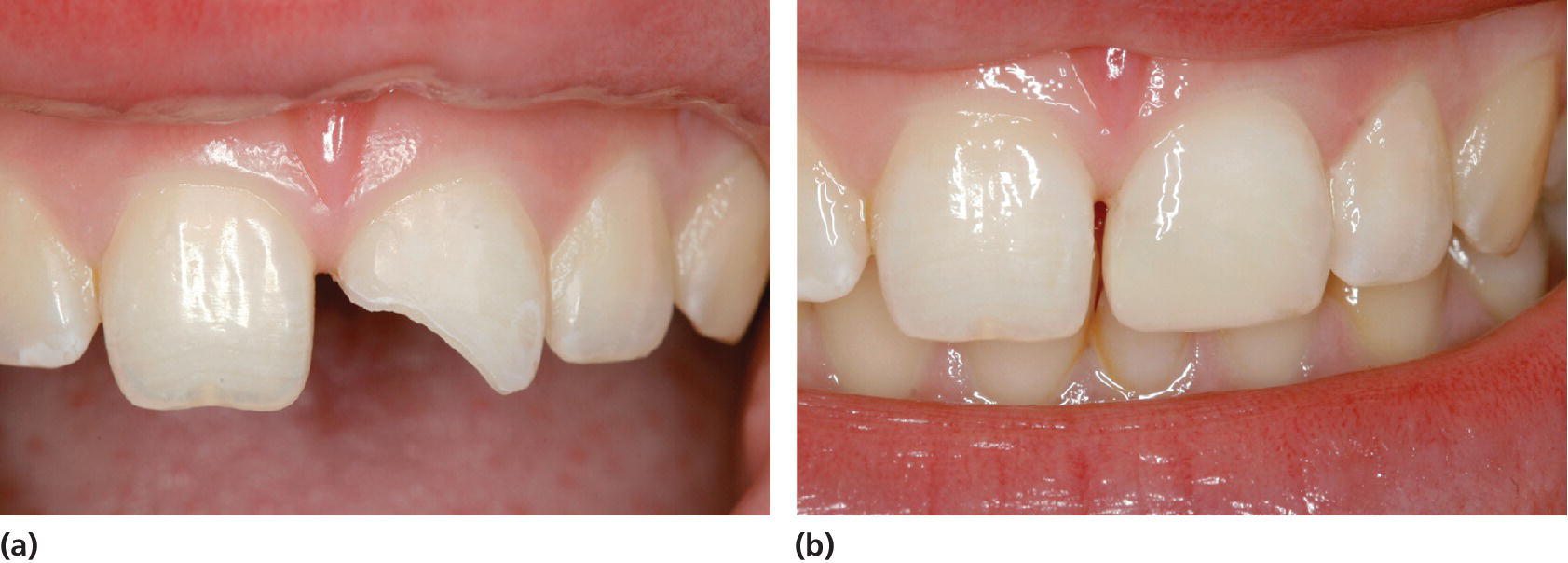

- Temporary crown restoration. There are situations in which a temporary restoration should be preferred over a period of time. One example is when the child’s general health condition is also affected. A temporary restoration may then be the most practical solution until the child has recovered. Another example is when an associated luxation injury requires immediate fixation, as shown in Figure 18.19. The procedure is to cover exposed dentin with calcium hydroxide. After etching, rinsing, and drying of the enamel, a layer of light‐curing composite resin is applied. Alternatively, the whole fracture surface can be covered with a glass ionomer cement “bandage.”

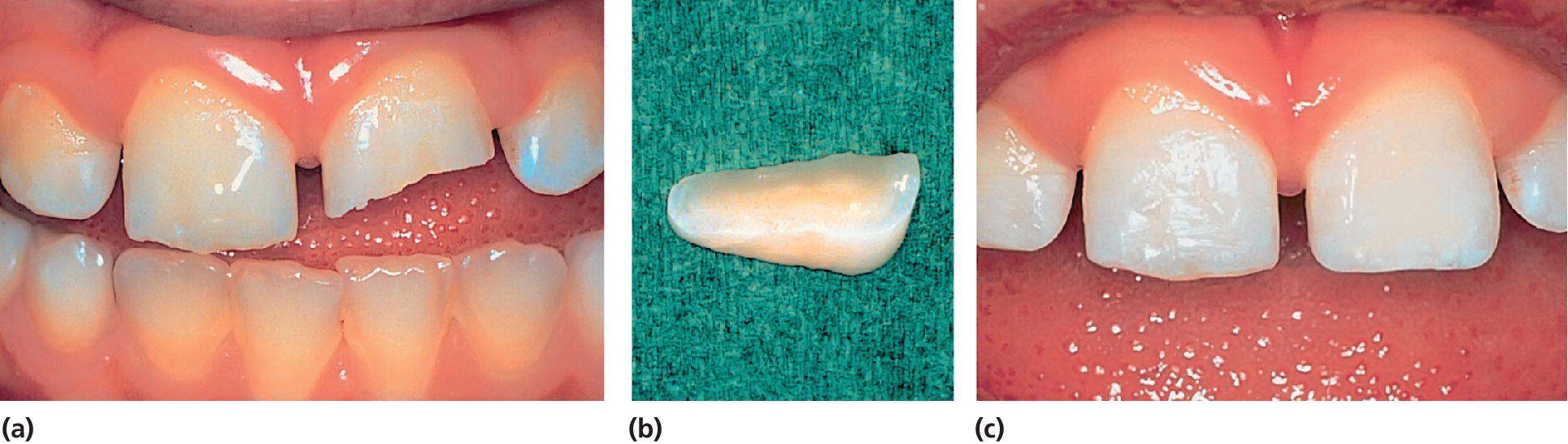

- Reattachment of a crown fragment. A tooth fragment from a traumatized incisor may be reattached. Dehydration of the fragment will decrease the bonding strength and lead to an inferior cosmetic result and must therefore be avoided. A dry fragment can be rehydrated before bonding. If a temporary restoration is indicated for a period of time, the fragment can be stored in physiologic saline in the delay period. The broken fragment can then be bonded to the tooth with a flowable composite (Figure 18.20) [15].

- Composite crown build‐up. If the fractured fragment is not found, or if it is too small to be reattached, a composite build‐up has been shown to be successful both functionally and esthetically in the young patient (Figure 18.21). The treatment procedure is summarized in Box 18.3.

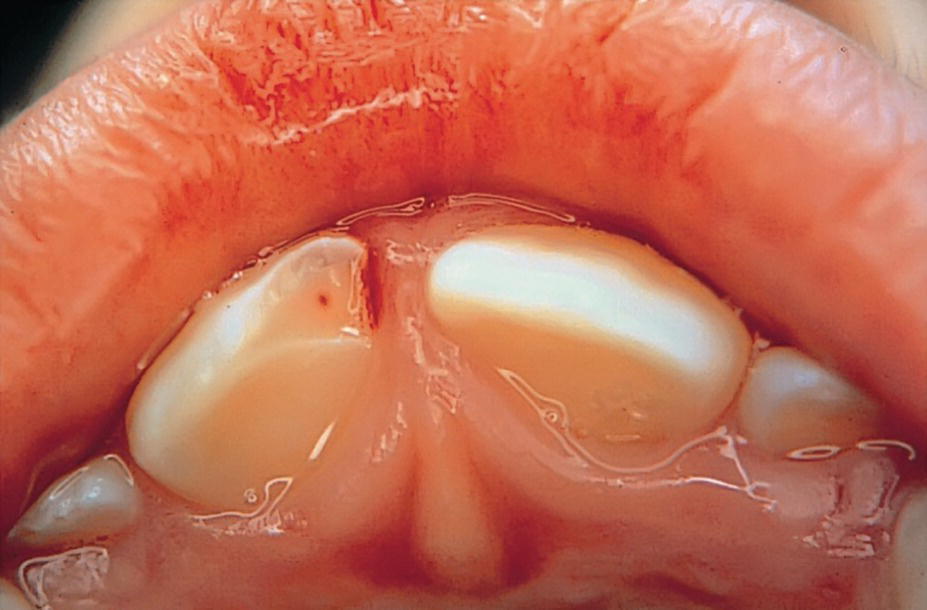

- Complicated crown fracture. This fracture involves enamel and dentin, with exposure of the pulp (Figure 18.22). The overall aim of the treatment is preservation of a vital noninflamed pulp. The pulp must be sealed from bacteria so that it is not infected during the period of repair. In most cases this can be achieved by either pulp capping or partial pulpotomy. The indications and techniques for these two treatment procedures are presented in Boxes 18.4 and 18.5 (see also Chapters 16 and 17).

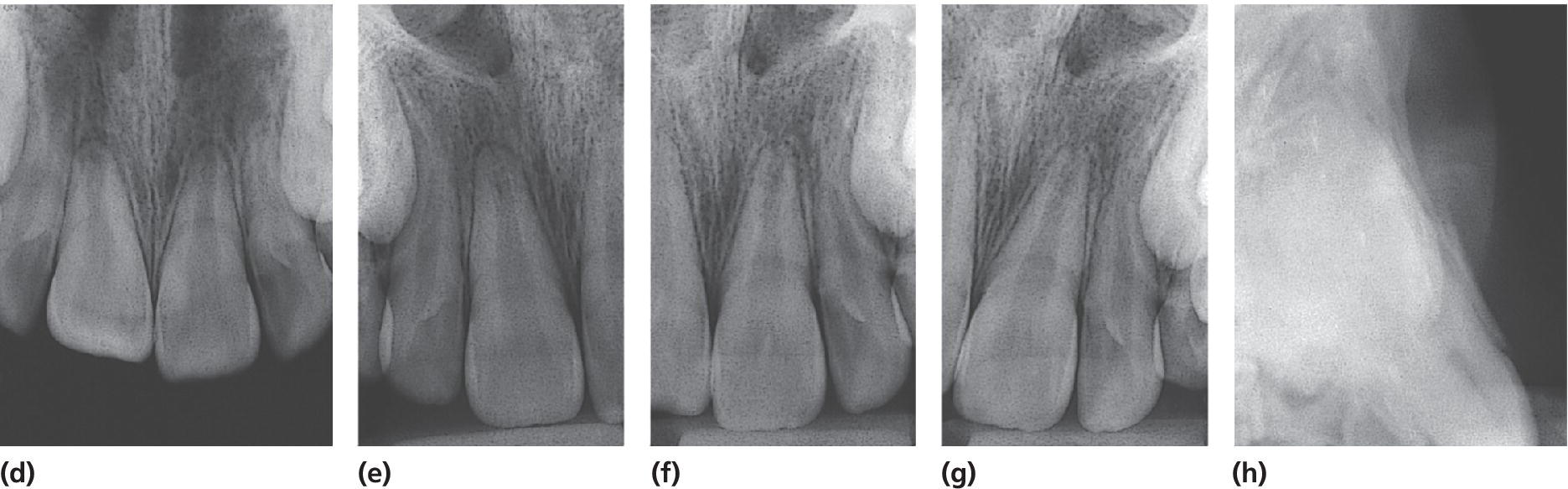

Figure 18.18 Uncomplicated crown fracture involving either mesial corners or entire incisal edge. The gingival bleeding indicates that intrusive luxation has also occurred in the right central incisor.

Figure 18.19 (a) Both subluxation and uncomplicated crown fracture have occurred in the left central incisor. (b) The tooth is stabilized with a splint, and a temporary crown restoration is applied.

Figure 18.20 (a) Enamel–dentin fracture of the left central incisor in an 8‐year‐old boy. (b) The fractured crown fragment. (c) Condition immediately after reattachment of the fragment.

Figure 18.21 (a) A 12‐year‐old girl with enamel–dentin fracture of the left central incisor. (b) Condition shortly after the composite crown build‐up.

Figure 18.22 Right central incisor with a small pulpal exposure, but with loosening and marked tenderness to percussion. Partial pulpotomy was decided to be the treatment of choice.

VIDEdental - Online dental courses